(Press-News.org) A system developed by investigators at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Engineering in Medicine allowed successful transplantation of rat livers after preservation for as long as four days, more than tripling the length of time organs currently can be preserved. The team describes their protocol – which combines below-freezing temperatures with the use of two protective solutions and machine perfusion of the organ – in a Nature Medicine paper receiving advance online publication.

"To our knowledge, this is the longest preservation time with subsequent successful transplantation achieved to date," says Korkut Uygun, PhD, of the MGH Center for Engineering in Medicine (MGH-CEM), co-senior author of the report. "If we can do this with human organs, we could share organs globally, helping to alleviate the worldwide organ shortage."

Once the supply of oxygen and nutrients is cut off from any organ, it begins to deteriorate. Since the 1980s, donor organs have been preserved at temperatures at or just above freezing (0˚ Celsius or 32˚ Fahrenheit) in a solution developed at the University of Wisconsin (UW solution), which reduces metabolism and organ deterioration ten-fold for up to 12 hours. Extending that preservation time, the authors note, could increase both the distance a donor organ could safely be transported and the amount of time available to prepare a recipient for the operation.

Keeping an organ at below-freezing temperatures, a process called supercooling, could extend preservation time by further slowing metabolism, it also could damage the organ in several ways. To reduce those risks the MGH-CEM protocol involves the use of two protective solutions – polyethylene glycol (PEG), which protects cell membranes, and a glucose derivative called 3-OMG, which is taken into liver cells.

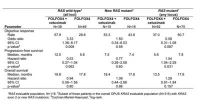

After removal from donor animals, the livers were attached to a machine perfusion system – in essence, an 'artificial body' that supports basic organ function – where they were first loaded with 3-OMG and then flushed with a combination of UW and PEG solutions while being cooled to 4˚C (40˚ F). The organs were then submerged in UW/PEG solution and stored at -6˚C (21˚F) for either 72 or 96 hours, after which the temperature was gradually increased back to 4˚C. The organs were then machine perfused with UW/PEG solution at room temperature for three hours before being transplanted into healthy rats.

All of the animals that received organs supercooled for 72 hours were healthy at the end of the three-month study follow-up period. Although only 58 percent of animals receiving organs supercooled for 96 hours survived for three months, analysis of several factors done while the organs were being rewarmed could distinguish between the organs that were and were not successfully transplanted.

"This ability to assess the livers prior to transplantation allows us to determine whether the supercooled organ is still good enough for transplantation," explains study co-author Bote Bruinsma, MSc, of the MGH-CEM. "Even among the livers preserved for four days, if we had only used those in which oxygen uptake, bile production and the flow of perfusion solution were good, we would have achieved 100 percent survival."

While much work needs to be done before this approach can be applied to human patients, extending how long an organ can safely be preserved may eventually allow the use of organs currently deemed unsuitable for transplant, notes Martin Yarmush, MD, PhD, founding director of MGH-CEM and co-senior author of the paper. "By reducing the damage that can occur during preservation and transportation, our supercooling protocol may permit use of livers currently considered marginal – something we will be investigating – which could further reduce the long waiting lists for transplants." Yarmush and Uygun are both on the faculty of Harvard Medical School.

INFORMATION: END

Massachusetts General-developed protocol could greatly extend preservation of donor livers

Supercooling and machine perfusion allow transplantation of rat livers preserved for up to four days

2014-06-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Reconstructing the life history of a single cell

2014-06-29

Researchers have developed new methods to trace the life history of individual cells back to their origins in the fertilised egg. By looking at the copy of the human genome present in healthy cells, they were able to build a picture of each cell's development from the early embryo on its journey to become part of an adult organ.

During the life of an individual, all cells in the body develop mutations, known as somatic mutations, which are not inherited from parents or passed on to offspring. These somatic mutations carry a coded record of the lifetime experiences of ...

Study finds Emperor penguin in peril

2014-06-29

An international team of scientists studying Emperor penguin populations across Antarctica finds the iconic animals in danger of dramatic declines by the end of the century due to climate change. Their study, published today in Nature Climate Change, finds the Emperor penguin "fully deserving of endangered status due to climate change."

The Emperor penguin is currently under consideration for inclusion under the US Endangered Species Act. Criteria to classify species by their extinction risk are based on the global population dynamics.

The study was conducted by lead ...

Noninvasive brain control

2014-06-29

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Optogenetics, a technology that allows scientists to control brain activity by shining light on neurons, relies on light-sensitive proteins that can suppress or stimulate electrical signals within cells. This technique requires a light source to be implanted in the brain, where it can reach the cells to be controlled.

MIT engineers have now developed the first light-sensitive molecule that enables neurons to be silenced noninvasively, using a light source outside the skull. This makes it possible to do long-term studies without an implanted light source. ...

Bending the rules

2014-06-29

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) — For his doctoral dissertation in the Goldman Superconductivity Research Group at the University of Minnesota, Yu Chen, now a postdoctoral researcher at UC Santa Barbara, developed a novel way to fabricate superconducting nanocircuitry. However, the extremely small zinc nanowires he designed did some unexpected — and sort of funky — things.

Chen, along with his thesis adviser, Allen M. Goldman, and theoretical physicist Alex Kamenev, both of the University of Minnesota, spent years seeking an explanation for these extremely puzzling effects. ...

Improved method for isotope enrichment could secure a vital global commodity

2014-06-29

AUSTIN, Texas — Researchers at The University of Texas at Austin have devised a new method for enriching a group of the world's most expensive chemical commodities, stable isotopes, which are vital to medical imaging and nuclear power, as reported this week in the journal Nature Physics. For many isotopes, the new method is cheaper than existing methods. For others, it is more environmentally friendly.

A less expensive, domestic source of stable isotopes could ensure continuation of current applications while opening up opportunities for new medical therapies and fundamental ...

Improved survival with TAS-102 in mets colorectal cancer refractory to standard therapies

2014-06-28

The new combination agent TAS-102 is able to improve overall survival compared to placebo in patients whose metastatic colorectal cancer is refractory to standard therapies, researchers said at the ESMO 16th World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer in Barcelona.

"Around 50% of patients with colorectal cancer develop metastases but eventually many of them do not respond to standard therapies," said Takayuki Yoshino of the National Cancer Centre Hospital East in Chiba, Japan, lead author of the phase III RECOURSE trial. "The RECOURSE study shows that TAS-102 improves overall ...

Cetuximab or bevacizumab with combi chemo equivalent in KRAS wild-type MCRC

2014-06-28

For patients with KRAS wild-type untreated colorectal cancer, adding cetuximab or bevacizumab to combination chemotherapy offers equivalent survival, researchers said at the ESMO 16th World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer in Barcelona.

"The CALGB/SWOG 80405 trial was designed and formulated in 2005, and the rationale was simple: we had new drugs --bevacizumab and cetuximab-- and the study was designed to determine if one was better than the other in first-line for patients with colon cancer," said lead study author Alan P. Venook, distinguished Professor of Medical ...

Herpes virus infection drives HIV infection among non-injecting drug users in New York

2014-06-27

HIV and its transmission has long been associated with injecting drug use, where hypodermic syringes are used to administer illicit drugs. Now, a newly reported study by researchers affiliated with New York University's Center for Drug Use and HIV Research (CDUHR) in the journal PLOS ONE, shows that HIV infection among heterosexual non-injecting drug users (no hypodermic syringe is used; drugs are taken orally or nasally) in New York City (NYC) has now surpassed HIV infection among persons who inject drugs.

The study, "HSV-2 Co-Infection as a Driver of HIV Transmission ...

Potential Alzheimer's drug prevents abnormal blood clots in the brain

2014-06-27

Without a steady supply of blood, neurons can't work. That's why one of the culprits behind Alzheimer's disease is believed to be the persistent blood clots that often form in the brains of Alzheimer's patients, contributing to the condition's hallmark memory loss, confusion and cognitive decline.

New experiments in Sidney Strickland's Laboratory of Neurobiology and Genetics at Rockefeller University have identified a compound that might halt the progression of Alzheimer's by interfering with the role amyloid-β, a small protein that forms plaques in Alzheimer's brains, ...

'Bad' video game behavior increases players' moral sensitivity

2014-06-27

BUFFALO, N.Y. — New evidence suggests heinous behavior played out in a virtual environment can lead to players' increased sensitivity toward the moral codes they violated.

That is the surprising finding of a study led by Matthew Grizzard, PhD, assistant professor in the University at Buffalo Department of Communication, and co-authored by researchers at Michigan State University and the University of Texas, Austin.

"Rather than leading players to become less moral," Grizzard says, "this research suggests that violent video-game play may actually lead to increased moral ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Study reveals ancient needles and awls served many purposes

Key protein SYFO2 enables 'self-fertilization’ of leguminous plants

AI tool streamlines drug synthesis

Turning orchard waste into climate solutions: A simple method boosts biochar carbon storage

New ACP papers say health care must be more accessible and inclusive for patients and physicians with disabilities

Moisture powered materials could make cleaning CO₂ from air more efficient

Scientists identify the gatekeeper of retinal progenitor cell identity

American Indian and Alaska native peoples experience higher rates of fatal police violence in and around reservations

Research alert: Long-read genome sequencing uncovers new autism gene variants

Genetic mapping of Baltic Sea herring important for sustainable fishing

In the ocean’s marine ‘snow,’ a scientist seeks clues to future climate

Understanding how “marine snow” acts as a carbon sink

In search of the room temperature superconductor: international team formulates research agenda

Index provides flu risk for each state

Altered brain networks in newborns with congenital heart disease

Can people distinguish between AI-generated and human speech?

New robotic microfluidic platform brings ai to lipid nanoparticle design

COSMOS trial results show daily multivitamin use may slow biological aging

Immune cells play key role in regulating eye pressure linked to glaucoma

National policy to remedy harms of race-based kidney function estimation associated with increased transplants for Black patients

Study finds teens spend nearly one-third of the school day on smartphones, with frequent checking linked to poorer attention

Team simulates a living cell that grows and divides

Study illuminates the experiences of people needing to seek abortion care out of state

Digital media use and child health and development

Seeking abortion care across state lines after the Dobbs decision

Smartphone use during school hours and association with cognitive control in youths ages 11 to 18

Maternal acetaminophen use and child neurodevelopment

Digital microsteps as scalable adjuncts for adults using GLP-1 receptor agonists

Researchers develop a biomimetic platform to enhance CAR T cell therapy against leukemia

Heart and metabolic risk factors more strongly linked to liver fibrosis in women than men, study finds

[Press-News.org] Massachusetts General-developed protocol could greatly extend preservation of donor liversSupercooling and machine perfusion allow transplantation of rat livers preserved for up to four days