(Press-News.org) A breakthrough discovery into how living cells process and respond to chemical information could help advance the development of treatments for a large number of cancers and other cellular disorders that have been resistant to therapy. An international collaboration of researchers, led by scientists with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California (UC) Berkeley, have unlocked the secret behind the activation of the Ras family of proteins, one of the most important components of cellular signaling networks in biology and major drivers of cancers that are among the most difficult to treat.

"Ras is a family of membrane-anchored proteins whose activation is a critical step in cellular signaling, but almost everything we know about how Ras signals are activated has been derived from bulk assays, in solution or in live cells, in which information about the role of the membrane environment and anything about variation among individual molecules is lost," says Jay Groves, a chemist with Berkeley Lab's Physical Biosciences Division and UC Berkeley's Chemistry Department. "Using a supported-membrane array platform, we were able to perform single molecule studies of Ras activation in a membrane environment and discover a surprising new mechanism though which Ras signaling is activated by Son of Sevenless (SOS) proteins."

Groves, who is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) investigator, is the corresponding author of a paper in Science that reports this discovery. The paper is titled "Ras activation by SOS: Allosteric regulation by altered fluctuation dynamics." The lead authors were Lars Iversen and Hsiung-Lin Tu, both members of Groves' research group at the time of the study. See below for a complete list of co-authors and their institutional affiliations.

The cellular signaling networks of living cells start with receptor proteins residing on a cell's surface that detect and interact with the environment. Signals from these receptors are transmitted to chemical networks within the cell that process the incoming information, make decisions, and direct subsequent cellular activities.

"Although cellular signaling networks perform logical operations like a computer microprocessor, they do not operate in the same way," Groves says. "The individual computational steps in a standard computer are deterministic; the outcome is determined by the inputs. For the chemical reactions that compose a cellular signaling network, however, the molecular level outcomes are defined by probabilities only. This means that the same input can lead to different outcomes."

For cellular signaling networks involving large numbers of protein molecules, the outcome can be directly determined by the process of averaging. Even though the behavior of an individual protein is intrinsically variable, the average behavior from a large group of identical proteins is precisely determined by molecular level probabilities. Ras activation in a living cell, however, involves a relatively small number of SOS molecules, making it impossible to average the variable behavior of the individual molecules. This variation is referred to as stochastic "noise" and has been widely viewed by scientists as an error a cell must overcome.

"Our study showed that, in fact, an important aspect of the SOS signal that activates Ras is encoded in the noise," says Groves. "The protein's dynamic fluctuations between different states of activity transmit information, which means we have found a regulatory coupling in a protein signaling reaction that is entirely based on dynamics, without any trace of the signal being seen in the average behavior."

The Ras Enigma

Ras proteins are essential components of signaling networks that control cellular proliferation, differentiation and survival. Mutations in Ras genes were the first specific genetic alterations linked to human cancers and it is now estimated that nearly a third of all human cancers can be traced to something going wrong with Ras activation. Defective Ras signaling has also been cited as a contributing factor to other diseases, including diabetes and immunological and inflammatory disorders. Despite this long history of recognized association with cancers and other diseases, Ras proteins have been dubbed "un-druggable," largely because their activation mechanism has been poorly understood.

A roadblock to understanding Ras signaling is that the membranes to which Ras proteins are anchored play a major role in their activation through SOS exchange factors. SOS activity in turn was believed to be allosterically regulated through protein and membrane interactions, but this was deduced from cell biological studies rather than direct observations. For a better understanding of how Ras activation by SOS is regulated, scientists need to observe individual SOS molecules interacting with Ras in a membrane environment. However, membrane environments have traditionally presented a stiff experimental challenge.

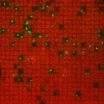

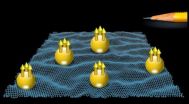

Groves and his research group overcame this challenge with the development of supported membrane arrays constructed out of lipid layers embedded with fixed patterns of metal nanostructures and assembled onto a silica substrate. The metal structures allow for the controlled spacing of proteins and other cellular molecules placed on the membranes. This makes it possible for the membranes to serve as a platform for assays that can be used to observe in real-time the activity of single molecules.

"In this case, our supported membrane allowed us to corral individual SOS molecules into nanofabricated patches that trapped all the membrane-associated Ras molecules they activated," Groves says. "This in turn allowed us to monitor the individual contribution of every molecule in the ensemble and reveal how the dynamic transitions of individual molecules encoded information that is lost in the average."

What the collaboration discovered is that SOS regulation is based on the dynamics of distinct stochastic fluctuations between different activity states that last approximately 100 seconds but do not show up in ensemble averages. These long-lived fluctuations provide the mechanism of allosteric SOS regulation and Ras activation.

"The allosteric regulation of SOS deduced from cell biological and bulk biochemical studies is conspicuously absent in direct single molecule studies," Groves says. "This means that something that was inferred to exist proved to be missing when we did an experiment that explicitly measured it. The dynamic fluctuations we observed within the system correlated with the expected allosteric regulation, and subsequent theoretical modeling confirmed that such stochastic fluctuations can give rise to known bulk effects."

Understanding the role of stochastic dynamic fluctuations as signaling transduction mechanisms for Ras proteins, could point the way to new and effective therapies for Ras-driven cancers and other cellular disorders. In their Science paper, the collaborators also express their belief that the dynamic fluctuations mechanism they discovered is not unique to Ras proteins but could be applicable to a broad range of other cellular signaling proteins.

"The reason this mechanism has not been reported before is that no previous experiment could have revealed it," Groves says. "All previous experiments on this system - and most others for that matter - were based on average behavior. Only single molecule measurements that can look at all the molecules in the system are capable of revealing this type of effect, which we think may prove to be very important in the function of living cell signaling systems."

INFORMATION:

Other co-authors of the Science paper were Wan-Chen Lin, Rebecca Petit, Scott Hansen, Peter Thill and Christopher Rhodes with UC Berkeley; Jeff Iwig and Jodi Gureasko, HHMI; Sune Christensen and Dimitrios Stamou, University of Copenhagen; Steven Abel, University of Tennessee; Hung-Jen Wu, Texas A&M; Cheng-Han Yu, National University of Singapore; Arup Chakraborty, MIT; and John Kuriyan, who also holds joint appointments with Berkeley Lab, UC Berkeley and HHMI.

This study was primarily supported by the National Institutes of Health, and leveraged collaborations with the Mechanobiology Institute in Singapore as part of the Berkeley Educational Alliance for Research in Singapore, and the Singapore CREATE program.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world's most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab's scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. For more, visit http://www.lbl.gov.

The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit http://www.science.energy.gov

.

New discovery in living cell signaling

Berkeley Lab researchers help find that what was believed to be noise is an important signaling factor

2014-07-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Compounded outcomes associated with comorbid Alzheimer's disease & cerebrovascular disease

2014-07-03

LEXINGTON, Ky. (July 3, 2014) -- Researchers from the Sanders-Brown Center on Aging at the University of Kentucky have been able to confirm anecdotal information on patients with both Alzheimer's disease (AD) and cerebrovascular disease (CVD) using mouse models in two different studies.

The findings of these two studies, which were recently published in Acta Neuropathologica and Alzheimer's Research & Therapy, have potentially significant implications for patients with both disorders.

Both papers studied CVD in Alzheimer's disease mouse models using different lifestyle ...

Biochemical cascade causes bone marrow inflammation, leading to serious blood disorders

2014-07-03

VIDEO:

Like a line of falling dominos, a cascade of molecular events in the bone marrow produces high levels of inflammation that disrupt normal blood formation and lead to potentially deadly...

Click here for more information.

INDIANAPOLIS -- Like a line of falling dominos, a cascade of molecular events in the bone marrow produces high levels of inflammation that disrupt normal blood formation and lead to potentially deadly disorders including leukemia, an Indiana University-led ...

How knots can swap positions on a DNA strand

2014-07-03

Physicists of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) and the Graduate School of Excellence "Materials Science in Mainz" (MAINZ) have been able with the aid of computer simulations to confirm and explain a mechanism by which two knots on a DNA strand can interchange their positions. For this, one of the knots grows in size while the other diffuses along the contour of the former. Since there is only a small free energy barrier to swap, a significant number of crossing events have been observed in molecular dynamics simulations, i.e., there is a high probability of such ...

From pencil marks to quantum computers

2014-07-03

Introducing graphene

One of the hottest materials in condensed matter research today is graphene.

Graphene had an unlikely start: it began with researchers messing around with pencil marks on paper. Pencil "lead" is actually made of graphite, which is a soft crystal lattice made of nothing but carbon atoms. When pencils deposit that graphite on paper, the lattice is laid down in thin sheets. By pulling that lattice apart into thinner sheets – originally using Scotch tape – researchers discovered that they could make flakes of crystal just one atom thick.

The name ...

Payback time for soil carbon from pasture conversion to sugarcane production

2014-07-03

The reduction of soil carbon stock caused by the conversion of pasture areas into sugarcane plantations – a very common change in Brazil in recent years – may be offset within two or three years of cultivation.

The calculation appears in a study conducted by researchers at the Center for Nuclear Energy in Agriculture (CENA) of the University of São Paulo (USP) in collaboration with colleagues from the Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture (Esalq), also at USP. The study also included researchers from the Federal Institute of Alagoas (IFAL), the Brazilian Bioethanol Science ...

New satellite data like an ultrasound for baby stars

2014-07-03

An international team of researchers have been monitoring the "heartbeats" of baby stars to test theories of how the Sun was born 4.5 billion years ago.

In a paper published in Science magazine today, the team of 20 scientists describes how data from two space telescopes – the Canadian Space Agency's MOST satellite and the French CoRoT mission – have unveiled the internal structures and ages of young stars before they've even emerged as full-fledged stars.

"Think of it as ultrasound of stellar embryos," explains University of British Professor Jaymie Matthews, MOST ...

A young star's age can be gleamed from nothing but sound waves

2014-07-03

VIDEO:

In a young region like the so-called Christmas Tree Cluster, stars are still in the process of forming. A star is 'born' once it becomes optically visible (bottom right). During...

Click here for more information.

Determining the age of stars has long been a challenge for astronomers. In experiments published in the journal Science, researchers at KU Leuven's Institute for Astronomy show that 'infant' stars can be distinguished from 'adolescent' stars by measuring the acoustic ...

Sweet genes

2014-07-03

Edmonton, July 3, 2014 – A research team at the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry at the University of Alberta have discovered a new way by which metabolism is linked to the regulation of DNA, the basis of our genetic code. The findings may have important implications for the understanding of many common diseases, including cancer.

The DNA wraps around specialized proteins called histones in the cell's nucleus. Normally, histones keep the DNA tightly packaged, preventing the expression of genes and the replication of DNA, which are required for cell growth and division. ...

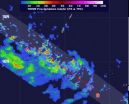

NASA sees rainfall in newborn Tropical Depression 8W

2014-07-03

Powerful thunderstorms in some areas of newborn Tropical Depression 08W in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean were dropping heavy rainfall on July 3 as NASA's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite passed overhead.

The eighth depression of the Northwestern Pacific Ocean season formed on July 3 at 0900 UTC (5 a.m. EDT). It was located near 10.0 north latitude and 144.3 east longitude about 240 nautical miles south of Andersen Air Force Base, Guam. Tropical Depression 08W or TD08W had maximum sustained winds near 30 knots (34.5 mph/55.5 kph) and it was moving ...

Safer, cheaper building blocks for future anti-HIV and cancer drugs

2014-07-03

A team of researchers from KU Leuven, in Belgium, has developed an economical, reliable and heavy metal-free chemical reaction that yields fully functional 1,2,3-triazoles. Triazoles are chemical compounds that can be used as building blocks for more complex chemical compounds, including pharmaceutical drugs.

Leveraging the compound's surprisingly stable structure, drug developers have successfully used 1,2,3-triazoles as building blocks in various anti-HIV, anti-cancer and anti-bacterial drugs. But efforts to synthesize the compound have been hampered by one serious ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

Calibr-Skaggs and Kainomyx launch collaboration to pioneer novel malaria treatments

JAX-NYSCF Collaborative and GSK announce collaboration to advance translational models for neurodegenerative disease research

Classifying pediatric brain tumors by liquid biopsy using artificial intelligence

Insilico Medicine initiates AI driven collaboration with leading global cancer center to identify novel targets for gastroesophageal cancers

Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy before surgery shows promise for pancreatic cancer

A “smart fluid” you can reconfigure with temperature

[Press-News.org] New discovery in living cell signalingBerkeley Lab researchers help find that what was believed to be noise is an important signaling factor