(Press-News.org) Nagoya, Japan – Professor Takashi Yoshimura and colleagues of the Institute of Transformative Bio-Molecules (WPI-ITbM) of Nagoya University have finally found the missing piece in how birds sense light by identifying a deep brain photoreceptor in Japanese quails, in which the receptor directly responds to light and controls seasonal breeding activity. Although it has been known for over 100 years that vertebrates apart from mammals detect light deep inside their brains, the true nature of the key photoreceptor has remained to be a mystery up until now. This study led by Professor Yoshimura has revealed that nerve cells existing deep inside the brains of quails, called cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-contacting neurons, respond directly to light. His studies also showed that these neurons are involved in detecting the arrival of spring and thus regulates breeding activities in birds. The study published online on July 7, 2014 in Current Biology is expected to contribute to the improvement of production of animals along with the deepening of our understanding on the evolution of eyes and photoreceptors.

Many organisms apart from those living in the tropics use the changes in the length of day (photoperiod) as their calendars to adapt to seasonal changes in the environment. In order to adapt, animals change their physiology and behavior, such as growth, metabolism, immune function and reproductive activity. "The mechanism of seasonal reproduction has been the focus of extensive studies, which is regulated by photoperiod" says Professor Yoshimura, who led the study, "small mammals and birds tend to breed during the spring and summer when the climate is warm and when there is sufficient food to feed their young offspring," he continues. In order to breed during this particular season, the animals are actually sensing the changes in the seasons based on changes in day length. "We have chosen quails as our targets, as they show rapid and robust photoperiodic responses. They are in the same pheasant family as the roosters and exhibit similar characteristics. It is also worth noting that Toyohashi near Nagoya is the number one producer of quails in Japan," explains Professor Yoshimura. The reproductive organs of quails remain small in size throughout the year and only develop during the short breeding season, becoming more than 100 times its usual size in just two weeks.

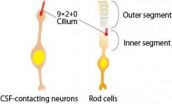

In most mammals including humans, eyes are the exclusive photoreceptor organs. Rhodopsin and rhodopsin family proteins in our eyes detect light and without our eyes, we are unable to detect light. On the other hand, vertebrates apart from mammals receive light directly inside their brains and sense the changes in day length. Therefore, birds for example, are able to detect light even when their eyes are blindfolded. Although this fact has been known for many years, the photoreceptor that undertakes this role had not yet been clarified. "We had already revealed in previous studies reported in 2010 (PNAS) that a photoreceptive protein, Opsin-5 exists in the quail's hypothalamus in the brain," says Professor Yoshimura. This Opsin-5 protein was expressed in the CSF-contacting neurons, which protrudes towards the third ventricle of the brain. "However, there was no direct evidence to show that the CSF-contacting neurons were detecting light directly and we decided to look into this," says Professor Yoshimura.

Yoshimura's group has used the patch-clamp technique for brain slices in order to investigate the light responses (action potential) of the CSF-contacting neurons. As a result, it was found that the cells were activated upon irradiation of light. "Even when the activities of neurotransmitters were inhibited, the CSF-contacting neurons' response towards light did not diminish, suggesting that they were directly responding to the light," says Professor Yoshimura excitedly. In addition, when the RNA interference method was used to inhibit the activity of the Opsin-5 protein expressed in the CSF-contacting neurons, the secretion of the thyroid-stimulating hormone from the pars tuberalis of the pituitary gland was inhibited. The thyroid-stimulating hormone, so-called the "spring calling hormone" stimulates another hormone, which triggers spring breeding in birds. "We have been able to show that the CSF-contacting neurons directly respond to light and are the key photoreceptors that control breeding activity in animals, which is what many biologists have been looking for over 100 years," elaborates Professor Yoshimura.

There have been many theories on the role of CSF-contacting neurons in response to light. "Our studies have revealed that these neurons are actually the photoreceptors working deep inside the bird's brain. As eyes are generated as a protrusion of the third ventricle, CSF-contacting neurons expressing Opsin-5, can be considered as an ancestral organ, which shares the same origin as the visual cells of the eyes. Opsin-5 also exists in humans and we believe that this research will contribute to learning how animals regulate their biological clocks and to find effective bio-molecules that can control the sensing of seasons," says Professor Yoshimura. Professor Yoshimura's quest to clarify how animals measure the length of time continues.

INFORMATION:

This article "Intrinsic photosensitivity of a deep brain photoreceptor" by Yusuke Nakane, Tsuyoshi Shimmura, Hideki Abe and Takashi Yoshimura is published online on July 7, 2014 in Current Biology, Volume 24, Issue 13, Pages R596-597.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.038

About WPI-ITbM

The World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI) for the Institute of Transformative Bio-Molecules (ITbM) at Nagoya University in Japan is committed to advance the integration of synthetic chemistry, plant/animal biology and theoretical science, all of which are traditionally strong fields in the university. As part of the Japanese science ministry's MEXT program, the ITbM aims to develop transformative bio-molecules, innovative functional molecules capable of bringing about fundamental change to biological science and technology. Research at the ITbM is carried out in a "Mix-Lab" style, where international young researchers from multidisciplinary fields work together side-by-side in the same lab. Through these endeavors, the ITbM will create "transformative bio-molecules" that will dramatically change the way of research in chemistry, biology and other related fields to solve urgent problems, such as environmental issues, food production and medical technology that have a significant impact on the society.

Shining light on the 100-year mystery of birds sensing spring for offspring

2014-07-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A healthy lifestyle adds years to life

2014-07-08

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory disorders - the incidence of these non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is constantly rising in industrialised countries. The Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) is, therefore, in the process of developing a national prevention strategy with a view to improving the population's health competence and encouraging healthier behaviour. Attention is focusing, amongst other things, on the main risk factors for these diseases which are linked to personal behaviour – i.e. tobacco smoking, an unhealthy diet, ...

HIV study leads to insights into deadly infection

2014-07-08

Research led by the University of Adelaide has provided new insights into how the HIV virus greatly boosts its chances of spreading infection, and why HIV is so hard to combat.

HIV infects human immune cells by turning the infection-fighting proteins of these cells into a "backdoor key" that lets the virus in. Recent research has found that another protein is involved as well. A peptide in semen that sticks together and forms structures known as "amyloid fibrils" enhances the virus's infection rate by up to an astonishing 10,000 times.

How and why these fibrils enhance ...

AAU launches STEM education initiative website, announces STEM network conference

2014-07-08

The Association of American Universities (AAU), an association of leading public and private research universities, today launched the AAU STEM Initiative Hub, a website that will both support and widen the impact of the association's initiative to improve the quality of

undergraduate teaching and learning in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields at its member institutions.

AAU has partnered with HUBzero, a web-based platform for scientific collaboration developed and managed by Purdue University, to create the AAU STEM Initiative Hub. The new ...

Silicon sponge improves lithium-ion battery performance

2014-07-08

RICHLAND, Wash. – The lithium-ion batteries that power our laptops and electric vehicles could store more energy and run longer on a single charge with the help of a sponge-like silicon material.

Researchers developed the porous material to replace the graphite traditionally used in one of the battery's electrodes, as silicon has more than 10 times the energy storage capacity of graphite. A paper describing the material's performance as a lithium-ion battery electrode was published today in Nature Communications.

"Silicon has long been sought as a way to improve the ...

Underage drinkers overexposed to magazine advertising for the brands they consume

2014-07-08

PISCATAWAY, NJ – The brands of alcohol popular with underage drinkers also happen to be the ones heavily advertised in magazines that young people read, a new study finds.

The findings, reported in July's Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, add to evidence that alcohol ads can encourage kids to drink.

They also suggest that the alcohol industry's self-imposed standards on advertising are inadequate, said lead researcher Craig Ross, Ph.D., M.B.A., of the Natick, Mass.,-based Virtual Media Resources.

"All of the ads in our study were in complete compliance with ...

Underage drinkers heavily exposed to magazine ads for alcohol brands they consume

2014-07-08

Underage drinkers between the ages of 18 and 20 see more magazine advertising than any other age group for the alcohol brands they consume most heavily, raising important questions about whether current alcohol self-regulatory codes concerning advertising are sufficiently protecting young people.

This is the conclusion of a new study from the Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth (CAMY) at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health that examined which age groups saw the most magazine advertising for the 25 alcohol brands most popular among underage boys and ...

Study reveals fungus in yogurt outbreak poses a threat to consumers

2014-07-08

The fungus responsible for an outbreak of contaminated Greek yogurt last year is not harmless after all but a strain with the ability to cause disease, according to research published in mBio®, the online open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

In September 2013, customers of Chobani brand Greek yogurt complained of gastrointestinal (GI) problems after consuming products manufactured in the company's Idaho plant. The company issued a recall, and it was believed at the time that the fungal contaminant Murcor circinelloides was only a potential danger ...

Sibling composition impacts childhood obesity risk

2014-07-08

Ann Arbor, MI, July 8, 2014 – It is well documented that children with obese parents are at greater risk for obesity. In a new study, researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital, Cornell University, and Duke University looked at how different kinds of family associations affect obesity, specifically how sibling relationships affect a child's weight. They not only found a correlation between parents and child, but also discovered a link between having an obese sibling and a child's obesity risk, after adjusting for the parent-child relationship. Their findings are published ...

New data shows proprietary calcium and collagen formulation KoACT® superior for bone health

2014-07-08

City of Industry, CA – July 8, 2014 – Data presented at April's Experimental Biology 2014 Annual Scientific Meeting shows that KoACT, a dietary supplement that combines a proprietary formulation of calcium and collagen is optimal for bone strength and flexibility in

post-menopausal women. The research was conducted by Bahram H. Arjmandi, Ph. D, RD, who is currently Margaret A. Sitton Named Professor and Chair of the Department of Nutrition, Food, and Exercise Sciences at The Florida State University (FSU).

Dr. Jennifer Gu, AIDP's Vice President of Research and Development, ...

Significant step towards blood test for Alzheimer's

2014-07-08

Scientists have identified a set of 10 proteins in the blood which can predict the onset of Alzheimer's, marking a significant step towards developing a blood test for the disease. The study, led by King's College London and UK proteomics company, Proteome Sciences plc, analysed over 1,000 individuals and is the largest of its kind to date.

There are currently no effective long-lasting drug treatments for Alzheimer's, and it is believed that many new clinical trials fail because drugs are given too late in the disease process. A blood test could be used to identify patients ...