(Press-News.org) The molecular scale behavior of water at a solid/liquid interface holds fundamental significance in a diverse set of technical and scientific contexts, ranging from the efficiency of oil mining to the activity of biological molecules. Recently, it has become recognized that both the physical interactions and the surface morphology have significant impact on the behavior of interfacial water, including the water structures and wetting properties of the surface.

In a new review, Chunlei Wang, Yizhou Yang and Haiping Fang of the Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics report recent advances in atom-level understanding of interfacial water that exhibits an ordered character on various solid surfaces at room or cryogenic temperature.

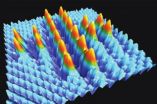

In recent decades, they report, "with the development of computer simulation tools and experimental tools, it is possible to obtain atomic level pictures of the water structure and the complex hydrogen bond network near the interfaces."

"Utilizing these tools, researchers have revealed that water structure may show appealing ordered structures depending on the surface morphology both at cryogenic temperatures and room temperature," they explain. "These ordered structures of water not only exhibit novel pictures but also affect the various surface properties, such as the surface electrochemical property, surface wetting behavior and surface frictions, etc."

"Special focus has been devoted to the wetting phenomenon of an "ordered water monolayer that does not completely wet water," along with the underlying mechanism, on model and real solid surfaces at room temperature," they report in the Beijing-based journal SCIENCE CHINA Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy.

The three scholars likewise outline possible applications of this phenomenon.

According to classical understanding, when water contacts other water, it will spread out and finally both mix together, i.e., water always completely wets water due to the hydrogen bonds formed among water molecules. In 2005, an ice monolayer that did not completely wet ice on metal Pt(111) surfaces was observed at extremely low temperatures.

It is well known that liquid water is essential for almost every biological process. Thus, if this exceptional behavior of liquid water exists, it might be crucial in understanding many biological activities.

Until relatively recently, this phenomenon had not been expected to be observed at room temperature. Like the superconductor and Bose–Einstein condensation, results obtained at cryogenic temperatures are usually not transferable to those observed at room temperature unless a new mechanism is introduced.

At room temperature, thermal fluctuations usually break the hydrogen bond networks in a water monolayer and lead to more hydrogen bonds formed between the monolayer and other water molecules. Thus, the water monolayer at room temperature is expected to completely wet water.

However, in 2009, Haiping Fang and co-researchers numerically observed a liquid water droplet on a water monolayer on a polar model surface at room temperature, and termed the phenomenon an "ordered water monolayer that does not completely wet water" (Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 137801).

This began to challenge the classical picture that a water monolayer always completely wets water. This work expanded understanding of hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity. The related mechanism lies in ordered water structures that reduce the possibilities of hydrogen bonds formed between the monolayer and the contacting water molecules above the monolayer. It should be noted that there remained a considerable number of dangling OH bonds in this room temperature water monolayer, in contrast with previous studies that did not report dangling OH bonds in the ordered water monolayer on a Pt(111) surface and a mica surface.

Over the past several years, more scientists have observed the phenomenon of a liquid water droplet on a water monolayer, both experimentally and numerically, on real surfaces including a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) surface with the terminal of –COOH, a BSA(bovine serum albumin)-Na2CO3 membrane, and an anatase and rutile TiO2 surface, a talc surface, a Pt(100) surface, a hydroxylated Al2O3 surface, a hydroxylated SiO2 surface.

INFORMATION:

This research received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 11290164, 11204341), the Knowledge Innovation Program of SINAP, the Knowledge Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Shanghai Supercomputer Center of China and the Supercomputing Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

See the article: C L Wang, YZ Yang, HP Fang, "Recent advances on an ordered water monolayer that does not completely wet water at room temperature." Sci China-Phys Mech Astron, 2014, 57: 802-809, doi: 10.1007/s11433-014-5415-3

http://phys.scichina.com:8083/sciGe/EN/abstract/abstract508766.shtml

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11433-014-5415-3

SCIENCE CHINA Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy is produced by Science China Press, which is a leading publisher of scientific journals in China that operates under the auspices of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Science China Press presents to the world leading-edge advancements made by Chinese scientists across a spectrum of fields.

http://www.scichina.com/

Shanghai scientists challenge classical phenomenon that water always completely wets water

2014-07-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

SWI assesses signal strength in different brain regions after acute hemorrhagic anemia

2014-07-15

Acute hemorrhagic anemia can decrease blood flow and oxygen supply to brain, and affect its physiological function. Detecting changes in brain function in patients with acute hemorrhagic anemia is helpful for preventing neurological complications and evaluating therapeutic effects. Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) imaging is a novel, non-invasive method for detecting changes in cerebral oxygen levels that may provide more detailed information regarding cerebral blood flow in patients with hemorrhage. Dr. Jun Xia, Second People's Hospital of Shenzhen City, First Affiliated ...

Taking B vitamins won't prevent Alzheimer's disease

2014-07-15

Taking B vitamins doesn't slow mental decline as we age, nor is it likely to prevent Alzheimer's disease, conclude Oxford University researchers who have assembled all the best clinical trial data involving 22,000 people to offer a final answer on this debate.

High levels in the blood of a compound called homocysteine have been found in people with Alzheimer's disease, and people with higher levels of homocysteine have been shown to be at increased risk of Alzheimer's disease. Taking folic acid and vitamin B-12 are known to lower levels of homocysteine in the body, so ...

How strongly does tissue decelerate the therapeutic heavy ion beam?

2014-07-15

Irradiation with heavy ions is suitable in particular for patients suffering from cancer with tumours which are difficult to access, for example in the brain. These particles hardly damage the penetrated tissue, but can be used in such a way that they deliver their maximum energy only directly at the target: the tumour. Research in this relatively new therapy method is focussed again and again on the exact dosing: how must the radiation parameters be set in order to destroy the cancerous cells "on the spot" with as low a damage as possible to the surrounding tissue? The ...

New hope for treatment of Alzheimer's disease

2014-07-15

Montreal, July 15 2014 - Judes Poirier, PhD, C.Q., from the Douglas Mental Health Institute and McGill University in Montréal (Canada) and his team have discovered that a relatively frequent genetic variant actually conveys significant protection against the common form of Alzheimer's disease and can delay the onset of the disease by as much as 4 years. This discovery opens new avenues for treatment against this devastating disease.

Dr. Poirier announced his findings as the annual Alzheimer's Association International Conference was taking place in Copenhagen. This large-scale ...

Smallest Swiss cross -- Made of 20 single atoms

2014-07-15

The manipulation of atoms has reached a new level: Together with teams from Finland and Japan, physicists from the University of Basel were able to place 20 single atoms on a fully insulated surface at room temperature to form the smallest "Swiss cross", thus taking a big step towards next generation atomic-scale storage devices. The academic journal Nature Communications has published their results.

Ever since the 1990s, physicists have been able to directly control surface structures by moving and positioning single atoms to certain atomic sites. A number of atomic ...

Cholesterol activates signaling pathway that promotes cancer

2014-07-15

Everyone knows that cholesterol, at least the bad kind, can cause heart disease and hardening of the arteries. Now, researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago describe a new role for cholesterol in the activation of a cellular signaling pathway that has been linked to cancer.

The finding is reported in Nature Communications.

Cells employ thousands of signaling pathways to conduct their functions. Canonical Wnt signaling is a pathway that promotes cell growth and division and is most active in embryonic cells during development. Overactivity of this signaling ...

Researchers assess emergency radiology response after Boston Marathon bombings

2014-07-15

OAK BROOK, Ill. – An after-action review of the Brigham and Women's Hospital emergency radiology response to the Boston Marathon bombings highlights the crucial role medical imaging plays in emergency situations and ways in which radiology departments can improve their preparedness for mass casualty events. The new study is published online in the journal Radiology.

"It's important to analyze our response to events like the Boston Marathon bombing to identify opportunities for improvement in our institutional emergency operations plan," said senior author Aaron Sodickson ...

No anti-clotting treatment needed for most kids undergoing spine surgeries

2014-07-15

Blood clots occur so rarely in children undergoing spine operations that most patients require nothing more than vigilant monitoring after surgery and should be spared risky and costly anti-clotting medications, according to a new Johns Hopkins Children's Center study.

Because clotting risk in children is poorly understood, treatment guidelines are largely absent, leaving doctors caring for pediatric patients at a loss on whom to treat and when.

The Johns Hopkins' team findings, published online July 15 in the journal Spine, narrow down the pool of high-risk patients ...

Little too late: Researchers identify disease that may have plagued 700-year-old skeleton

2014-07-15

European researchers have recovered a genome of the bacterium Brucella melitensis from a 700-year-old skeleton found in the ruins of a Medieval Italian village.

Reporting this week in mBio®, the online open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology, the authors describe using a technique called shotgun metagenomics to sequence DNA from a calcified nodule in the pelvic region of a middle-aged male skeleton excavated from the settlement of Geridu in Sardinia, an island off the coast of Italy. Geridu is thought to have been abandoned in the late 14th century. ...

Study reveals how gardens could help dementia care

2014-07-15

A new study has revealed that gardens in care homes could provide promising therapeutic benefits for patients suffering from dementia.

The research is published in the Journal of the American Medical Directors Association and by critically reviewing the findings from 17 different pieces of research, has found that outdoor spaces can offer environments that promote relaxation, encourage activity and reduce residents' agitation.

Conducted by a team at the University of Exeter Medical School and supported by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for ...