(Press-News.org) ST. LOUIS – In results recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Saint Louis University scientists have discovered that removal of disordered sections of a protein's structure reveals the molecular mechanism of a key reaction that initiates blood clotting.

Enrico Di Cera, M.D., chair of the Edward A. Doisy department of biochemistry and molecular biology at Saint Louis University, studies thrombin, a key vitamin K-dependent blood-clotting protein, and its inactive precursor prothrombin (or coagulation factor II).

"Prothrombin is essential for life and is the most important clotting factor," Di Cera said. "We are proud to report that our lab here at SLU has finally succeeded in crystallizing prothrombin for the first time."

Blood-clotting has long ensured our survival, stopping blood loss after an injury. However, when triggered in the wrong circumstances, clotting can lead to debilitating or fatal conditions such as a heart attack, stroke or deep vein thrombosis.

Before thrombin becomes active, it circulates throughout the blood in the inactive (zymogen) form called prothrombin. When the active enzyme is needed (after a vascular injury, for example), the coagulation cascade is initiated and prothrombin is converted into the active enzyme thrombin that causes blood to clot.

X-ray crystallography is one tool in scientists' toolbox for understanding processes at the molecular level. It offers a way to obtain a "snap shot" of a protein's structure.

In this technique, scientists grow crystals of the protein they want to study, shoot x-rays at them and record data about the way the rays are scattered by crystals. Then they use computer programs to create an image of the protein based on that data.

Once scientists can visualize the three dimensional structure of a molecule, they can begin to piece together the way in which the protein functions and interacts with other molecules in the body, or with drugs.

Last year, Di Cera and colleagues published the first structure of prothrombin. This first structure lacked a domain responsible for interaction with membranes and certain other sections were not detected by x-ray analysis. Though the scientists were able to crystallize the protein, there were disordered regions in the structure that they could not see.

Within prothrombin there are two kringle domains (looped sections of a protein named after the Scandinavian pastry) connected by a "linker" region that intrigued the SLU investigators because of its intrinsic disorder.

"We deleted this linker and crystals grew in a few days instead of months, revealing for the first time the full architecture of prothrombin," Di Cera said.

In addition to this remarkable discovery, Di Cera and colleagues found that the deleted version of prothrombin is activated to thrombin much faster than the intact prothrombin. The structure without the disordered linker is in fact optimized for conversion to thrombin and reveals key information on the mechanism of prothrombin activation.

For over four decades, scientists have tried to crystallize prothrombin but without success.

"It took us almost two years to discover that the disordered linker was the key," Di Cera said. "Finally, prothrombin revealed its secrets and with that the molecular mechanism of a key reaction of blood clotting finally becomes amenable to rational drug design for therapeutic intervention."

INFORMATION:

SLU researchers Nicola Pozzi, Ph.D., Zhiwei Chen, Leslie Pelc and Daniel Shropshire also are authors on the paper.

Established in 1836, Saint Louis University School of Medicine has the distinction of awarding the first medical degree west of the Mississippi River. The school educates physicians and biomedical scientists, conducts medical research, and provides health care on a local, national and international level. Research at the school seeks new cures and treatments in five key areas: cancer, liver disease, heart/lung disease, aging and brain disease, and infectious disease.

SLU scientists hit 'delete': Removing regions of shape-shifting protein explains how blood clots

2014-07-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New skin gel fights breast cancer without blood clot risk

2014-07-15

CHICAGO --- A gel form of tamoxifen applied to the breasts of women with noninvasive breast cancer reduced the growth of cancer cells to the same degree as the drug taken in oral form but with fewer side effects that deter some women from taking it, according to new Northwestern Medicine® research.

Tamoxifen is an oral drug that is used for breast cancer prevention and as therapy for non-invasive breast cancer and invasive cancer.

Because the drug was absorbed through the skin directly into breast tissue, blood levels of the drug were much lower, thus, potentially ...

Game theory model reveals vulnerable moments for cancer cells' energy production

2014-07-15

Cancer's no game, but researchers at Johns Hopkins are borrowing ideas from evolutionary game theory to learn how cells cooperate within a tumor to gather energy. Their experiments, they say, could identify the ideal time to disrupt metastatic cancer cell cooperation and make a tumor more vulnerable to anti-cancer drugs.

"The reality is that we still can't cure metastatic cancer that has spread from its primary organ and game theory adds to our efforts to attack the problem," says Kenneth J. Pienta, M.D., the Donald S. Coffey Professor of Urology at the Johns Hopkins ...

Adolescent males seek intimacy and close relationships with the opposite sex

2014-07-15

July 15, 2014 -- Teenage boys desire intimacy and sex in the context of a meaningful relationship and value trust in their partnerships, according to researchers at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health. The research provides a snapshot of the development of masculine values in adolescence, an area that has been understudied. Findings are online in the American Journal of Men's Health.

The researchers studied 33 males who ranged from 14 to 16 years of age to learn more about how their romantic and sexual relationships developed, progressed, and ended. ...

Fish oil supplements reduce incidence of cognitive decline, may improve memory function

2014-07-15

PROVIDENCE, R.I. –Rhode Island Hospital researchers have completed a study that found regular use of fish oil supplements (FOS) was associated with a significant reduction in cognitive decline and brain atrophy in older adults. The study examined the relationship between FOS use during the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) and indicators of cognitive decline. The findings are published online in advance of print in the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia.

"At least one person is diagnosed every minute with Alzheimer's disease (AD) and despite best efforts, ...

Brain responses to emotional images predict PTSD symptoms after Boston Marathon bombing

2014-07-15

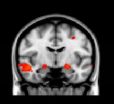

The area of the brain that plays a primary role in emotional learning and the acquisition of fear – the amygdala – may hold the key to who is most vulnerable to post-traumatic stress disorder.

Researchers at the University of Washington, Boston Children's Hospital, Harvard Medical School and Boston University collaborated on a unique opportunity to study whether patterns of brain activity predict teenagers' response to a terrorist attack.

The team had already performed brain scans on Boston-area adolescents for a study on childhood trauma. Then in April 2013 two bombs ...

Study finds unintended consequences of raising state math, science graduation requirements

2014-07-15

WASHINGTON, D.C., July 15, 2014 ─ Raising state-mandated math and science course graduation requirements (CGRs) may increase high school dropout rates without a meaningful effect on college enrollment or degree attainment, according to new research published in Educational Researcher (ER), a peer-reviewed journal of the American Educational Research Association.

VIDEO: Co-authors Andrew D. Plunk and William F. Tate discuss key findings. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jwxh1gj-T1M&feature=youtu.be

"Intended and Unintended Effects of State-Mandated High School ...

BUSM study: Obesity may be impacted by stress

2014-07-15

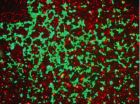

Using experimental models, researchers at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) showed that adenosine, a metabolite released when the body is under stress or during an inflammatory response, stops the process of adipogenesis, when adipose (fat) stem cells differentiate into adult fat cells.

Previous studies have indicated adipogenesis plays a central role in maintaining healthy fat homeostasis by properly storing fat within cells so that it does not accumulate at high levels in the bloodstream. The current findings indicate that the body's response to stress, potentially ...

Team studies immune response of Asian elephants infected with a human disease

2014-07-15

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the organism that causes tuberculosis in humans, also afflicts Asian (and occasionally other) elephants. Diagnosing and treating elephants with TB is a challenge, however, as little is known about how their immune systems respond to the infection. A new study begins to address this knowledge gap, and offers new tools for detecting and monitoring TB in captive elephants.

The study, reported in the journal Tuberculosis, is the work of researchers at the University of Illinois Zoological Pathology Program (ZPP), a division of ...

Protein's 'hands' enable bacteria to establish infection, research finds

2014-07-15

MANHATTAN — When it comes to infecting humans and animals, bacteria need a helping hand.

Kansas State University biochemists have found the helping hand: groups of tiny protein loops on the surface of cells. These loops are similar to the fingers of a hand, and by observing seven individual loops on the surface of E. coli bacterial cells, the researchers found that the loops can open or close to grab iron in the environment.

"These structures are like small hands on the surface of bacterial cells," said Phillip Klebba, principal investigator and professor and head of ...

4 lessons for effective, efficient research in health care settings

2014-07-15

Thousands of studies take place every year in healthcare settings. A report published recently in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine describes how to do many of these studies more rapidly. By taking into account the real-world constraints of the systems in which providers deliver care and patients receive it, researchers can help speed results, cut costs, and increase chances that recommendations from their findings will be implemented.

The lessons come from the My Own Health Report project, a collaboration between seven research institutions with the goal ...