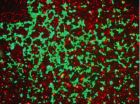

(Press-News.org) FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. - Cryptococcus gattii, a virulent fungus that has invaded the Pacific Northwest is highly adaptive and warrants global "public health vigilance," according to a study by an international team led by the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen).

C. gattii, which likely originated in Brazil, is responsible for dozens of deaths in recent years since it was first found in 1999 on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, well outside its usual tropical habitats.

"We identified several genes that may make the outbreak strains more capable of surviving colder environments and that make it more harmful in the lungs," said David Engelthaler, Director of Programs and Operations for TGen's Pathogen Genomics Division (TGen North) and lead author of the study published today in the scientific journal mBio.

This study should form the basis of additional investigations about how and why C. gattii disperses and emerges. It identified several new genomic targets for diagnostic tests, and possible new targets for therapeutic drugs and preventative vaccines.

"By closely analyzing the genomes of dozens of outbreak strains, as well as globally diverse strains, we were able to closely compare and determine the genomic differences that may cause their clinical and ecological changes," said Dr. Paul Keim, one of the study's senior authors. Dr. Keim also is Director of TGen North, and Director of the Microbial Genetics and Genomics Center at Northern Arizona University (NAU).

TGen, working with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others, conducted one of the largest global fungal genome analyses of a specific species to understand its emergence in new environments. The collaborative team included 24 researchers from 13 institutions in seven nations who sequenced 115 genomes of C. gattii collected from 15 countries.

"By thinking globally, we were able to better understand what was happening locally," Engelthaler said.

C. gattii was typically a tropical fungus before it was discovered in the temperate environs of Vancouver Island. It soon evolved into a new, more virulent, pulmonary disease that quickly spread to mainland Canada and south into the state of Washington. That was followed by an outbreak in Oregon of another new strain of C. gattii, which also displayed increased lethality and similarly spread throughout the Pacific Northwest.

C. gattii previously was associated with neurological disease in strains found elsewhere in the world. But the strains discovered in the Pacific Northwest not only establish a new environmental niche, but also display increased virulence and produce severe lung infections.

"We provide evidence that the Pacific Northwest strains originated from South America, and identified numerous genes potentially related to habitat adaptation, virulence expression and to clinical presentation," said Dr. Wieland Meyer, the study's other senior author.

"Further elucidation and characterization of these genetic features may lead to improved diagnostics and therapies for infections caused by this continually evolving fungus," said Dr. Meyer, who is affiliated with: Sydney Medical School-Westmead Hospital; the University of Sydney; and the Westmead Millennium Institute for Medical Research.

This study concludes that: "Public health vigilance is warranted for emergence in

regions where C. gattii is not thought to be endemic."

New tests developed for this study by TGen are making it easier to detect this and other fungi, and could lead to better monitoring and treatments. The same tools used in this study also were used to investigate the cause of a fungal meningitis outbreak associated with steroid back injections, and the recent outbreak of Valley Fever in the state of Washington.

INFORMATION:

The journal, mBio, is published by the American Society for Microbiology.

Collaborators in this study include researchers at the University of California-Davis, and in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Caledonia, Thailand, Columbia, and Brazil.

The study, "Cryptococcus gattii in North American Pacific Northwest: whole population genome analysis provides insights into species evolution and dispersal," was supported by a grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Medical Research Council (MRC) of South Africa.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the NIH under Award Number R21AI098059. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

About TGen

Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen) is a Phoenix, Arizona-based non-profit organization dedicated to conducting groundbreaking research with life changing results. TGen is focused on helping patients with cancer, neurological disorders and diabetes, through cutting edge translational research (the process of rapidly moving research towards patient benefit). TGen physicians and scientists work to unravel the genetic components of both common and rare complex diseases in adults and children. Working with collaborators in the scientific and medical communities literally worldwide, TGen makes a substantial contribution to help our patients through efficiency and effectiveness of the translational process. For more information, visit: http://www.tgen.org.

Press Contact

Steve Yozwiak

TGen Senior Science Writer

602-343-8704

syozwiak@tgen.org

TGen-led study finds likely origin of lung fungus invading Pacific Northwest

Cryptococcus gattii evolving as it spreads to temperate climates

2014-07-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Rice nanophotonics experts create powerful molecular sensor

2014-07-15

Nanophotonics experts at Rice University have created a unique sensor that amplifies the optical signature of molecules by about 100 billion times. Newly published tests found the device could accurately identify the composition and structure of individual molecules containing fewer than 20 atoms.

The new imaging method, which is described this week in the journal Nature Communications, uses a form of Raman spectroscopy in combination with an intricate but mass reproducible optical amplifier. Researchers at Rice's Laboratory for Nanophotonics (LANP) said the single-molecule ...

SLU scientists hit 'delete': Removing regions of shape-shifting protein explains how blood clots

2014-07-15

ST. LOUIS – In results recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Saint Louis University scientists have discovered that removal of disordered sections of a protein's structure reveals the molecular mechanism of a key reaction that initiates blood clotting.

Enrico Di Cera, M.D., chair of the Edward A. Doisy department of biochemistry and molecular biology at Saint Louis University, studies thrombin, a key vitamin K-dependent blood-clotting protein, and its inactive precursor prothrombin (or coagulation factor II).

"Prothrombin is essential ...

New skin gel fights breast cancer without blood clot risk

2014-07-15

CHICAGO --- A gel form of tamoxifen applied to the breasts of women with noninvasive breast cancer reduced the growth of cancer cells to the same degree as the drug taken in oral form but with fewer side effects that deter some women from taking it, according to new Northwestern Medicine® research.

Tamoxifen is an oral drug that is used for breast cancer prevention and as therapy for non-invasive breast cancer and invasive cancer.

Because the drug was absorbed through the skin directly into breast tissue, blood levels of the drug were much lower, thus, potentially ...

Game theory model reveals vulnerable moments for cancer cells' energy production

2014-07-15

Cancer's no game, but researchers at Johns Hopkins are borrowing ideas from evolutionary game theory to learn how cells cooperate within a tumor to gather energy. Their experiments, they say, could identify the ideal time to disrupt metastatic cancer cell cooperation and make a tumor more vulnerable to anti-cancer drugs.

"The reality is that we still can't cure metastatic cancer that has spread from its primary organ and game theory adds to our efforts to attack the problem," says Kenneth J. Pienta, M.D., the Donald S. Coffey Professor of Urology at the Johns Hopkins ...

Adolescent males seek intimacy and close relationships with the opposite sex

2014-07-15

July 15, 2014 -- Teenage boys desire intimacy and sex in the context of a meaningful relationship and value trust in their partnerships, according to researchers at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health. The research provides a snapshot of the development of masculine values in adolescence, an area that has been understudied. Findings are online in the American Journal of Men's Health.

The researchers studied 33 males who ranged from 14 to 16 years of age to learn more about how their romantic and sexual relationships developed, progressed, and ended. ...

Fish oil supplements reduce incidence of cognitive decline, may improve memory function

2014-07-15

PROVIDENCE, R.I. –Rhode Island Hospital researchers have completed a study that found regular use of fish oil supplements (FOS) was associated with a significant reduction in cognitive decline and brain atrophy in older adults. The study examined the relationship between FOS use during the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) and indicators of cognitive decline. The findings are published online in advance of print in the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia.

"At least one person is diagnosed every minute with Alzheimer's disease (AD) and despite best efforts, ...

Brain responses to emotional images predict PTSD symptoms after Boston Marathon bombing

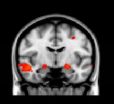

2014-07-15

The area of the brain that plays a primary role in emotional learning and the acquisition of fear – the amygdala – may hold the key to who is most vulnerable to post-traumatic stress disorder.

Researchers at the University of Washington, Boston Children's Hospital, Harvard Medical School and Boston University collaborated on a unique opportunity to study whether patterns of brain activity predict teenagers' response to a terrorist attack.

The team had already performed brain scans on Boston-area adolescents for a study on childhood trauma. Then in April 2013 two bombs ...

Study finds unintended consequences of raising state math, science graduation requirements

2014-07-15

WASHINGTON, D.C., July 15, 2014 ─ Raising state-mandated math and science course graduation requirements (CGRs) may increase high school dropout rates without a meaningful effect on college enrollment or degree attainment, according to new research published in Educational Researcher (ER), a peer-reviewed journal of the American Educational Research Association.

VIDEO: Co-authors Andrew D. Plunk and William F. Tate discuss key findings. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jwxh1gj-T1M&feature=youtu.be

"Intended and Unintended Effects of State-Mandated High School ...

BUSM study: Obesity may be impacted by stress

2014-07-15

Using experimental models, researchers at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) showed that adenosine, a metabolite released when the body is under stress or during an inflammatory response, stops the process of adipogenesis, when adipose (fat) stem cells differentiate into adult fat cells.

Previous studies have indicated adipogenesis plays a central role in maintaining healthy fat homeostasis by properly storing fat within cells so that it does not accumulate at high levels in the bloodstream. The current findings indicate that the body's response to stress, potentially ...

Team studies immune response of Asian elephants infected with a human disease

2014-07-15

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the organism that causes tuberculosis in humans, also afflicts Asian (and occasionally other) elephants. Diagnosing and treating elephants with TB is a challenge, however, as little is known about how their immune systems respond to the infection. A new study begins to address this knowledge gap, and offers new tools for detecting and monitoring TB in captive elephants.

The study, reported in the journal Tuberculosis, is the work of researchers at the University of Illinois Zoological Pathology Program (ZPP), a division of ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Stem cells from human baby teeth show promise for treating cerebral palsy

Chimps’ love for crystals could help us understand our own ancestors’ fascination with these stones

Vaginal estrogen therapy not linked to cancer recurrence in survivors of endometrial cancer

How estrogen helps protect women from high blood pressure

Breaking the efficiency barrier: Researchers propose multi-stage solar system to harness the full spectrum

A new name, a new beginning: Building a green energy future together

From algorithms to atoms: How artificial intelligence is accelerating the discovery of next-generation energy materials

Loneliness linked to fear of embarrassment: teen research

New MOH–NUS Fellowship launched to strengthen everyday ethics in Singapore’s healthcare sector

Sungkyunkwan University researchers develop next-generation transparent electrode without rare metal indium

What's going on inside quantum computers?: New method simplifies process tomography

This ancient plant-eater had a twisted jaw and sideways-facing teeth

Jackdaw chicks listen to adults to learn about predators

Toxic algal bloom has taken a heavy toll on mental health

Beyond silicon: SKKU team presents Indium Selenide roadmap for ultra-low-power AI and quantum computing

Sugar comforts newborn babies during painful procedures

Pollen exposure linked to poorer exam results taken at the end of secondary school

7 hours 18 mins may be optimal sleep length for avoiding type 2 diabetes precursor

Around 6 deaths a year linked to clubbing in the UK

Children’s development set back years by Covid lockdowns, study reveals

Four decades of data give unique insight into the Sun’s inner life

Urban trees can absorb more CO₂ than cars emit during summer

Fund for Science and Technology awards $15 million to Scripps Oceanography

New NIH grant advances Lupus protein research

New farm-scale biochar system could cut agricultural emissions by 75 percent while removing carbon from the atmosphere

From herbal waste to high performance clean water material: Turning traditional medicine residues into powerful biochar

New sulfur-iron biochar shows powerful ability to lock up arsenic and cadmium in contaminated soils

AI-driven chart review accurately identifies potential rare disease trial participants in new study

Paleontologist Stephen Chester and colleagues reveal new clues about early primate evolution

UF research finds a gentler way to treat aggressive gum disease

[Press-News.org] TGen-led study finds likely origin of lung fungus invading Pacific NorthwestCryptococcus gattii evolving as it spreads to temperate climates