(Press-News.org) Scientists may be able to entomb the malaria parasite in a prison of its own making, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report July 16 in Nature.

As it invades a red blood cell, the malaria parasite takes part of the host cell's membrane to build a protective compartment. To grow properly, steal nourishment and dump waste, the parasite then starts a series of major renovations that transform the red blood cell into a suitable home.

But the new research reveals the proteins that make these renovations must pass through a single pore in the parasite's compartment to get into the red blood cell. When the scientists disrupted passage through that pore in cell cultures, the parasite stopped growing and died.

"The malaria parasite secretes hundreds of diverse proteins to seize control of red blood cells," said first author Josh R. Beck, PhD, a postdoctoral research scholar. "We've been searching for a single step that all those various proteins have to take to be secreted, and this looks like just such a bottleneck."

A separate study by researchers at the Burnet Institute and Deakin University in Australia, published in the same issue of Nature, also highlights the importance of the pore to the parasite's survival. Researchers believe blocking the pore leaves the parasite fatally imprisoned, unable to steal resources from the red blood cell or dispose of its wastes.

The malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, is among the world's deadliest pathogens. Malaria is spread mainly by the bite of infected mosquitoes and is most common in Africa. In 2012, an estimated 207 million cases of malaria occurred worldwide, leading to 627,000 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. Resistance to drug treatments is spreading among the parasite's many strains, and researchers are working hard to find new drug targets.

Senior author Daniel Goldberg, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and of molecular microbiology and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator at Washington University, studies how malaria affects red blood cells.

In the new study, he and his colleagues looked at heat shock protein 101 (HSP101). Scientists named this family of proteins "heat shock" because they become active when cells are overheated or stressed. The proteins have multiple functions, including guiding the folding and unfolding of other proteins.

Previous studies have suggested that HSP101 might be involved in protein secretion. The researchers disabled HSP101 in cell cultures, expecting to block the discharge of some malarial proteins. To their surprise, they stopped all of them.

"We think this is a very promising target for drug development," Goldberg said. "We're a long way from getting a new drug, but in the short term we may look at screening a variety of compounds to see if they have the potential to block HSP101."

The scientists think HSP101 may ready malarial proteins for secretion through a pore that opens into the red blood cell. Part of this preparation may involve unfolding the proteins into a linear form that allows them to more easily pass through the narrow pore. HSP101 may also give the proteins a biochemical kick that pushes them through the pore.

Beck noted that researchers at the Burnet Institute neutralized the parasite in a similar fashion by disabling another protein thought to be involved in the passage of proteins through this pore.

"That suggests there are multiple components of the process that we may be able to target with drugs," he said. "In addition, many of the proteins involved in secretion are unlike any human proteins, which means we may be able to disable them without adversely affecting important human proteins."

INFORMATION:

Funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) supported this research. Grant numbers AI047798, T32-AI007172 and AI099156.

Beck JR, Muralidharan V, Oksman A, Goldberg DE. HSP101/PTEX mediates export of diverse malaria effector proteins into the host erthyrocyte. Nature, published online July 16, 2014.

Washington University School of Medicine's 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient-care institutions in the nation, currently ranked sixth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

Scientists find way to trap, kill malaria parasite

2014-07-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Asteroid Vesta to reshape theories of planet formation

2014-07-16

EPFL researchers have a better understanding of the asteroid Vesta and its internal structure, thanks to numerical simulations and data from the space mission Dawn. Their findings, published today in Nature, question contemporary models of rocky planet formation, including that of Earth.

With its 500 km diameter, the asteroid Vesta is one of the largest known planet embryos. It came into existence at the same time as the Solar System. Spurring scientific interest, NASA sent the Dawn spacecraft into Vesta's orbit for one year between July 2011 and July 2012.

Data gathered ...

NASA sees Typhoon Rammasun exit the Philippines

2014-07-16

Typhoon Rammasun passed through the central Philippines overnight and NASA satellite imagery showed that the storm's center moved into the South China Sea. NASA's TRMM satellite showed the soaking rains that Rammasun brought to the Philippines as it tracked from east to west.

Before Rammasun made landfall, the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission or TRMM satellite passed over the storm and measured cloud heights and rainfall rates. On July 14, 2014 at 18:19 UTC (2:19 p.m. EDT), TRMM spotted powerful, high thunderstorms reaching heights of almost 17km (10.5 miles). Rain ...

Researchers demonstrate health risks posed by 'third hand' tobacco smoke

2014-07-16

Research led by the University of York has highlighted the potential cancer risk in non-smokers – particularly young children – of tobacco smoke gases and particles deposited to surfaces and dust in the home.

Until now, the risks of this exposure known as 'third hand tobacco smoke' have been highly uncertain and not considered in public policy.

However, a new study published in the journal Environment International, has estimated for the first time the potential cancer risk by age group through non-dietary ingestion and dermal exposure to third hand smoke. The results ...

Squid skin protein could improve biomedical technologies, UCI study shows

2014-07-16

Irvine, Calif., July 16, 2014 – The common pencil squid (Loliginidae) may hold the key to a new generation of medical technologies that could communicate more directly with the human body. UC Irvine materials science researchers have discovered that reflectin, a protein in the tentacled creature's skin, can conduct positive electrical charges, or protons, making it a promising material for building biologically inspired devices.

Currently, products such as retinal implants, nerve stimulators and pacemakers rely on electrons – particles with negative charges – to transmit ...

National Psoriasis Foundation awards $1.05 million in research grants

2014-07-16

PORTLAND, Ore. (July 16, 2014)—Thirteen scientists received a total of $1.05 million in funding from the National Psoriasis Foundation for projects that aim to identify new treatments and a cure for psoriasis—an autoimmune disease that appears on the skin, affecting 7.5 million Americans—and psoriatic arthritis—an inflammatory arthritis that affects the joints and tendons, occurring in up to 30 percent of people with psoriasis.

Learn more about the NPF research grant program: http://www.psoriasis.org/research.

This year, three scientists each received a two-year, $200,000 ...

70-foot-long, 52-ton concrete bridge survives series of simulated earthquakes

2014-07-16

VIDEO:

A 70-foot-long, 52-ton concrete bridge survived a series of earthquakes in the first multiple-shake-table experiment in the University of Nevada, Reno's new Earthquake Engineering Lab, the newest addition to the...

Click here for more information.

RENO, Nev. – A 70-foot-long, 52-ton concrete bridge survived a series of earthquakes in the first multiple-shake-table experiment in the University of Nevada, Reno's new Earthquake Engineering Lab, the newest addition to the ...

Dozens of fires plague Oregon

2014-07-16

Fires are a way of life during the hot, dry summer days, but that does not mean they are ever taken for granted. Thousands of lightning strikes Sunday (7/13) and early Monday (7/14) probably started most of the wildfires, which are burning on private, public and reservation land. Dozens of fires are plaguing the forest areas in the state of Oregon. In this image, are shown the Buzzard Fire, the Shaniko Butte fire, the Bridge 99 Complex fire, and the Saddle Draw Fire.

The Buzzard Complex fire began as a lightning strike. Difficult terrain, combined with extremely dry ...

Arizona State University, US Geological Survey project yields sharpest map of Mars surface properties

2014-07-16

Tempe, Ariz. -- A heat-sensing camera designed at Arizona State University has provided data to create the most detailed global map yet made of Martian surface properties.

The map uses data from the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS), a nine-band visual and infrared camera on NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter. A version of the map optimized for scientific researchers is available at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

The new Mars map was developed by the Geological Survey's Robin Fergason at the USGS Astrogeology Science Center in Flagstaff, Ariz., in collaboration ...

Organismal biologists needed to interpret new trees of life

2014-07-16

Rapidly accumulating data on the molecular sequences of animal genes are overturning some standard zoological narratives about how major animal groups evolved. The turmoil means that biologists should adopt guidelines to ensure that their evolutionary scenarios remain consistent with new information—which a surprising number of scenarios are not, according to a critical overview article to be published in the August issue of BioScience and now available with Advance Access.

The article, by Ronald A Jenner of the Natural History Museum in London, describes how evolutionary ...

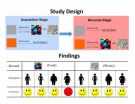

When it comes to food, obese women's learning is impaired

2014-07-16

Obese women were better able to identify cues that predict monetary rewards than those that predict food rewards, according to a study by Yale School of Medicine researchers and their colleagues in the journal Current Biology. The findings could result in specific behavioral interventions to treat obesity.

"Instead of focusing on reactions to the food itself, such interventions could focus on modifying the way in which obese individuals learn about the environment and about cues predicting food rewards," said lead author Ifat Levy, assistant professor of comparative medicine ...