(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Salk scientists have discovered the gene responsible for the aggressive spread of a common lung cancer.

Click here for more information.

LA JOLLA—Scientists at the Salk Institute have identified a gene responsible for stopping the movement of cancer from the lungs to other parts of the body, indicating a new way to fight one of the world's deadliest cancers.

By identifying the cause of this metastasis—which often happens quickly in lung cancer and results in a bleak survival rate—Salk scientists are able to explain why some tumors are more prone to spreading than others. The newly discovered pathway, detailed today in Molecular Cell, may also help researchers understand and treat the spread of melanoma and cervical cancers.

"Lung cancer, even when it's discovered early, is often able to metastasize almost immediately and take hold throughout the body," says Reuben J. Shaw, Salk professor of molecular and cell biology and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute early career scientist. "The reason behind why some tumors do that and others don't has not been very well understood. Now, through this work, we are beginning to understand why some subsets of lung cancer are so invasive."

Lung cancer, which also affects nonsmokers, is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the country (estimated to be nearly 160,000 this year). The United States spends more than $12 billion on lung cancer treatments, according to the National Cancer Institute. Nevertheless, the survival rate for lung cancer is dismal: 80 percent of patients die within five years of diagnosis largely due to the disease's aggressive tendency to spread throughout the body.

To become mobile, cancer cells override cellular machinery that typically keeps cells rooted within their respective locations. Deviously, cancer can switch on and off molecular anchors protruding from the cell membrane (called focal adhesion complexes), preparing the cell for migration. This allows cancer cells to begin the processes to traverse the body through the bloodstream and take up residence in new organs.

In addition to different cancers being able to manipulate these anchors, it was also known that about a fifth of lung cancer cases are missing an anti-cancer gene called LKB1 (also known as STK11). Cancers missing LKB1 are often aggressive, rapidly spreading through the body. However, no one knew how LKB1 and focal adhesions were connected.

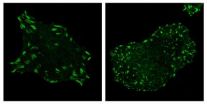

Now, the Salk team has found the connection and a new target for therapy: a little-known gene called DIXDC1. The researchers discovered that DIXDC1 receives instructions from LKB1 to go to focal adhesions and change their size and number.

When DIXDC1 is "turned on," half a dozen or so focal adhesions grow large and sticky, anchoring cells to their spot. When DIXDC1 is blocked or inactivated, focal adhesions become small and numerous, resulting in hundreds of small "hands" that pull the cell forward in response to extracellular cues. That increased tendency to be mobile aids in the escape from, for example, the lungs and allows tumor cells to survive travel through the bloodstream and dock at organs throughout the body.

"The communication between LKB1 and DIXDC1 is responsible for a 'stay-put' signal in cells," says first author and Ph.D. graduate student Jonathan Goodwin. "DIXDC1, which no one knew much about, turns out to be inhibited in cancer and metastasis."

Tumors, Shaw and collaborators found in the new research, have two ways to turn off this "stay-put" signal. One is by inhibiting DIXDC1 directly. The other way is by deleting LKB1, which then never sends the signal to DIXDC1 to move to the focal adhesions to anchor the cell. Given this, the scientists wondered if reactivating DIXDC1 could halt a cancer's metastasis. The team took metastatic cells, which had low levels of DIXDC1, and overexpressed the gene. The addition of DIXDC1 did indeed blunt the ability of these cells to be metastatic in vitro and in vivo.

"It was very, very surprising that this gene would be so powerful," says Goodwin. "At the start of this study, we had no idea DIXDC1 would be involved in metastasis. There are dozens of proteins that LKB1 affects; for a single one to control so much of this phenotype was not expected."

Right now, there is no specific treatment for cancers harboring LKB1 or DIXDC1 alterations, but those with a deletion of either gene would likely see results from cancer drugs that target the focal adhesions, says Shaw.

"The good news is that this finding predicts that patients missing either gene should be sensitive to new therapies targeting focal adhesion enzymes, which are currently being tested in early-stage clinical trials," says Shaw, who is also a member of the Moores Cancer Center and an adjunct professor at the University of California, San Diego.

"By identifying this unexpected connection between DIXDC1 and LKB1 in certain tumors, we have expanded the potential patient population that may be good candidates for these therapies," adds Goodwin.

INFORMATION:

Collaborators included Robert U. Svensson of the Salk Institute, Hua Jane Lou and Benjamin E. Turk of Yale University School of Medicine, and Monte M. Winslow of Stanford University.

The work was funded by: grants from the National Cancer Institute, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, MD, the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

New gene discovered that stops the spread of deadly cancer

Salk scientists identify gene that fights metastasis of a common lung cancer

2014-07-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

International research team discovers genetic dysfunction connected to hydrocephalus

2014-07-17

The mysterious condition once known as "water on the brain" became just a bit less murky this week thanks to a global research group led in part by a Case Western Reserve researcher. Professor Anthony Wynshaw-Boris, MD, PhD, is the co-principal investigator on a study that illustrates how the domino effect of one genetic error can contribute to excessive cerebrospinal fluid surrounding the brains of mice — a disorder known as hydrocephalus. The findings appear online July 17 in the journal Neuron.

Cerebrospinal fluid provides a cushion between the organ and the skull, ...

A region and pathway found crucial for facial development in vertebrate embryos

2014-07-17

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (July 17, 2014) – A signaling pathway once thought to have little if any role during embryogenesis is a key player in the formation of the front-most portion of developing vertebrate embryos. Moreover, signals emanating from this region—referred to as the "extreme anterior domain" (EAD)—orchestrate the complex choreography that gives rise to proper facial structure.

The surprising findings, reported by Whitehead Institute scientists this week in the journal Cell Reports, shed new light on a key process of vertebrate embryonic development.

"The results ...

Tak Mak study in Cancer Cell maps decade of discovery to potential anticancer agent

2014-07-17

(TORONTO, Canada – July 17, 2014) – The journal Cancer Cell today published research led by Dr. Tak Mak mapping the path of discovery to developing a potential anticancer agent.

"What began with the question 'what makes a particular aggressive form of breast cancer cells keep growing?' turned into 10 years of systematic research to identify the enzyme PLK4 as a promising therapeutic target and develop a small molecule inhibitor to block it," says Dr. Mak, Director of The Campbell Family Institute for Breast Cancer Research at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University ...

Gender quotas work in 'tight' cultures, says new paper from the University of Toronto

2014-07-17

Toronto – Quotas probably won't get more women into the boardroom in places like the U.S. and Canada.

They have a better chance however in countries such as China or Germany where people place a higher value on obeying authority and conforming to cultural norms, say a pair of researchers at the University of Toronto's Rotman School of Management. Their conclusions are published in the journal Organizational Dynamics and in a blog for the Harvard Business Review.

It all comes down to a culture's "tightness" or "looseness" -- the degree to which a culture maintains social ...

A new view of the world

2014-07-17

New research out of Queen's University has shed light on how exercise and relaxation activities like yoga can positively impact people with social anxiety disorders.

Adam Heenan, a Ph.D. candidate in the Clinical Psychology, has found that exercise and relaxation activities literally change the way people perceive the world, altering their perception so that they view the environment in a less threatening, less negative way. For people with mood and anxiety disorders, this is an important breakthrough.

For his research, Mr. Heenan used point-light displays, a depiction ...

Transplant patients who receive livers from living donors more likely to survive

2014-07-17

(PHILADELPHIA) – Research derived from early national experience of liver transplantation has shown that deceased donor liver transplants offered recipients better survival rates than living donor liver transplants, making them the preferred method of transplantation for most physicians. Now, the first data-driven study in over a decade disputes this notion. Penn Medicine researchers found that living donor transplant outcomes are superior to those found with deceased donors with appropriate donor selection and when surgeries are performed at an experienced center. The ...

GW researcher unlocks next step in creating HIV-1 immunotherapy using fossil virus

2014-07-17

WASHINGTON (July 17, 2014) — The road to finding a cure for HIV-1 is not without obstacles. However, thanks to cutting-edge research by Douglas Nixon, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues, performed at the George Washington University (GW), Oregon Health & Science University, the University of Rochester, and UC San Francisco, the scientific community is one step closer to finding a viable immunotherapy option for HIV-1, using an immune attack against a fossil virus buried in the genome.

A major hurdle in eradicating HIV-1 has been outsmarting the frequent mutations, or changing ...

Oregon geologist says Curiosity's images show Earth-like soils on Mars

2014-07-17

EUGENE, Ore. -- Soil deep in a crater dating to some 3.7 billion years ago contains evidence that Mars was once much warmer and wetter, says University of Oregon geologist Gregory Retallack, based on images and data captured by the rover Curiosity.

NASA rovers have shown Martian landscapes littered with loose rocks from impacts or layered by catastrophic floods, rather than the smooth contours of soils that soften landscapes on Earth. However, recent images from Curiosity from the impact Gale Crater, Retallack said, reveal Earth-like soil profiles with cracked surfaces ...

Is the universe a bubble? Let's check

2014-07-17

Never mind the big bang; in the beginning was the vacuum. The vacuum simmered with energy (variously called dark energy, vacuum energy, the inflation field, or the Higgs field). Like water in a pot, this high energy began to evaporate – bubbles formed.

Each bubble contained another vacuum, whose energy was lower, but still not nothing. This energy drove the bubbles to expand. Inevitably, some bubbles bumped into each other. It's possible some produced secondary bubbles. Maybe the bubbles were rare and far apart; maybe they were packed close as foam.

But here's the thing: ...

Orthopedic surgery generally safe for patients age 80 and older

2014-07-17

ROSEMONT, Ill.─Over the past decade, a greater number of patients, age 80 and older, are having elective orthopaedic surgery. A new study appearing in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (JBJS) found that these surgeries are generally safe with mortality rates decreasing for total hip (THR) and total knee (TKR) replacement and spinal fusion surgeries, and complication rates decreasing for total knee replacement and spinal fusion in patients with few or no comorbidities (other conditions or diseases).

"Based on the results of this study, I think very elderly patients, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

GLP-1 drugs associated with reduced need for emergency care for migraine

New knowledge on heritability paves the way for better treatment of people with chronic inflammatory bowel disease

Under the Lens: Microbiologists Nicola Holden and Gil Domingue weigh in on the raw milk debate

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

[Press-News.org] New gene discovered that stops the spread of deadly cancerSalk scientists identify gene that fights metastasis of a common lung cancer