(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

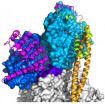

This is a representation of the atomic structure of tropomodulin at the minus end of the actin filament in muscle sarcomeres. Tropomodulin interacts with the first three actin subunits of...

Click here for more information.

PHILADELPHIA - Actin is the most abundant protein in the body, and when you look more closely at its fundamental role in life, it's easy to see why. It is the basis of most movement in the body, and all cells and components within them have the capacity to move: muscle contracting, heart beating, blood clotting, and nerve cells communicating, among many other functions. And, movement can turn harmful when cancer cells break away from tumors to set up shop in distant tissues.

Adding to the growing fundamental understanding of the machinery of muscle cells, a group of biophysicists from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania describe in the journal Science this week – in minute detail -- how actin filaments are stabilized at one of their ends to form a basic muscle structure called the sarcomere.

With the help of many other proteins, actin molecules polymerize to form filaments that give rise to structures of many different shapes. The actin filaments have a polarity, with a plus and minus end, reflecting their natural tendency to gain or lose subunits when not stabilized.

Actin is one of the two major proteins (together with myosin) that form the sarcomere -- the contractile structures of cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle cells. In sarcomeres, actin filaments are stabilized at both ends by capping proteins. At the minus end of the filament, the universal capping protein is tropomodulin.

"While the existence of this protein has been known for almost 30 years, we still did not know how it actually works," says senior author Roberto Dominguez, PhD, professor of Physiology. His lab is dedicated to deciphering the fundamental mechanisms of proteins responsible for movement, and how these components fit together at the atomic level.

"We describe how tropomodulin interacts with the slow-growing end of actin filaments," says coauthor Yadaiah Madasu, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Dominquez lab. "From a clinical point of view, we know that mutations in tropomodulin can trigger an accumulation of irregular actin filament bundles, which contribute to nemaline myopathy or other skeletal muscle disorders typified by delayed motor development and muscle weakness."

"The lack of structural information for the minus end of the actin filament severely limits our understanding of how tropomodulin caps actin," says Dominguez. The team described atomic crystal structures of tropomodulin complexes with actin. The structures and biochemical analysis of engineered tropomodulin variants show how one tropomodulin molecule winds around the minus end of an actin filament, making highly specific interactions with three actin subunits and two tropomyosin molecules (another protein characteristic of muscle sarcomeres) on each end of the actin filament. The detailed picture emerging from this study will help shed light on how mutations in tropomodulin, actin, and tropomysin can cause heart disorders.

The team is now studying another muscle protein called leiomodin. It was discovered more recently and resembles tropomodulin, but appears to have a completely different function, by participating in the development and repair of muscle sarcomeres.

INFORMATION:

Postdoctoral fellow Jampani Nageswara Rao, PhD, was first author on the paper. The research was supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01 GM073791). X-ray data collection at Beamline X6A of the National Synchrotron Light Source was supported by NIH grant GM-0080 and U.S. Department of Energy contract DE-AC02CH10886.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4.3 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine has been ranked among the top five medical schools in the United States for the past 17 years, according to U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $392 million awarded in the 2013 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania -- recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; Chester County Hospital; Penn Wissahickon Hospice; and Pennsylvania Hospital -- the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional affiliated inpatient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region include Chestnut Hill Hospital and Good Shepherd Penn Partners, a partnership between Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Network and Penn Medicine.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2013, Penn Medicine provided $814 million to benefit our community.

Atomic structure of key muscle component revealed in Penn study

2014-07-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Increased risk for head, neck cancers in patients with diabetes

2014-07-25

Diabetes mellitus (DM) appears to increase the risk for head and neck cancer (HNC). Evidence suggests certain cancers are more common in people with DM, but the risk of HNC in patients with DM has not been well explored. Overall, head and neck cancer is the sixth most common type of cancer. It accounts for about 6 percent of all cases and for an estimated 650,000 new cancer cases and 350,000 cancer deaths worldwide each year.

The authors used Taiwan's Longitudinal Health Insurance Research Database to examine the risk of HNC in patients with DM. The authors compared 89,089 ...

8.2 percent of our DNA is 'functional'

2014-07-25

Only 8.2% of human DNA is likely to be doing something important – is 'functional' – say Oxford University researchers.

This figure is very different from one given in 2012, when some scientists involved in the ENCODE (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) project stated that 80% of our genome has some biochemical function.

That claim has been controversial, with many in the field arguing that the biochemical definition of 'function' was too broad – that just because an activity on DNA occurs, it does not necessarily have a consequence; for functionality you need to demonstrate ...

Invertebrate numbers nearly halve as human population doubles

2014-07-25

Invertebrate numbers have decreased by 45% on average over a 35 year period in which the human population doubled, reports a study on the impact of humans on declining animal numbers. This decline matters because of the enormous benefits invertebrates such as insects, spiders, crustaceans, slugs and worms bring to our day-to-day lives, including pollination and pest control for crops, decomposition for nutrient cycling, water filtration and human health.

The study, published in Science and led by UCL, Stanford and UCSB, focused on the demise of invertebrates in particular, ...

Farmers market vouchers may boost produce consumption in low-income families

2014-07-25

Vouchers to buy fresh fruits and vegetables at farmers markets increase the amount of produce in the diets of some families on food assistance, according to research led by NYU's Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development.

The study, which appears online in Food Policy, suggests that farmers market vouchers can be useful tools in improving access to healthy food. This finding validates a new program created by the Agricultural Act of 2014, or farm bill, that incentivizes low-income families to buy produce at farmers markets.

"In terms of healthy ...

Researchers discover new way to determine cancer risk of chemicals

2014-07-25

BOSTON -- A new study has shown that it is possible to predict long-term cancer risk from a chemical exposure by measuring the short-term effects of that same exposure. The findings, which currently appear in the journal PLOS ONE, will make it possible to develop simpler and cheaper tests to screen chemicals for their potential cancer causing risk.

Despite an overall decrease in incidence of and mortality from cancer, about 40 percent of Americans will be diagnosed with the disease in their lifetime, and around 20 percent will die of it. Currently fewer than two percent ...

Less than 1 percent of UK public research funding spent on antibiotic research in past 5 years

2014-07-25

Less than 1% of research funding awarded by public and charitable bodies to UK researchers in 2008 was awarded for research on antibiotics, according to new research published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

The study, which is the first detailed assessment of public and charitable funding to UK researchers focusing on bacteriology and antibiotic research, suggests that present levels of funding for antibiotic research in the UK are inadequate, and will need to be urgently increased if the growing crisis of antibiotic resistance is to be tackled effectively by UK ...

Synchronization of North Atlantic, North Pacific preceded abrupt warming, end of ice age

2014-07-25

CORVALLIS, Ore. -- Scientists have long been concerned that global warming may push Earth's climate system across a "tipping point," where rapid melting of ice and further warming may become irreversible -- a hotly debated scenario with an unclear picture of what this point of no return may look like.

A newly published study by researchers at Oregon State University probed the geologic past to understand mechanisms of abrupt climate change. The study pinpoints the emergence of synchronized climate variability in the North Pacific Ocean and the North Atlantic Ocean a few ...

A world first: Researchers identify a treatment that prevents tumor metastasis

2014-07-25

Metastasis, the strategy adopted by tumor cells to transform into an aggressive form of cancer, are often associated with a gloomy prognosis. Managing to block the metastasis or, even better, prevent their formation would be a giant step towards the fight against cancer. Researchers at Université catholique de Louvain (Belgium) successfully performed this world first on models of human tumors in mice. The results of their study are published online on 24 July in the prestigious journal Cell Reports.

The work by Professor Pierre Sonveaux's team, at Université catholique ...

Noise pollution impacts fish species differently

2014-07-25

Acoustic disturbance has different effects on different species of fish, according to a new study from the Universities of Bristol and Exeter which tested fish anti-predator behaviour.

Three-spined sticklebacks responded sooner to a flying seagull predator model when exposed to additional noise, whereas no effects were observed in European minnows.

Lead author Dr Irene Voellmy of Bristol's School of Biological Sciences said: "Noise levels in many aquatic environments have increased substantially during the last few decades, often due to increased shipping traffic. ...

Four-billion-year-old chemistry in cells today

2014-07-25

Parts of the primordial soup in which life arose have been maintained in our cells today according to scientists at the University of East Anglia.

Research published today in the Journal of Biological Chemistry reveals how cells in plants, yeast and very likely also in animals still perform ancient reactions thought to have been responsible for the origin of life – some four billion years ago.

The primordial soup theory suggests that life began in a pond or ocean as a result of the combination of metals, gases from the atmosphere and some form of energy, such as a lightning ...