(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Salk scientists have discovered the link between astrocytes and memory.

Click here for more information.

LA JOLLA—When you're expecting something—like the meal you've ordered at a restaurant—or when something captures your interest, unique electrical rhythms sweep through your brain.

These waves are called gamma oscillations and they reflect a symphony of cells—both excitatory and inhibitory—playing together in an orchestrated way. Though their role has been debated, gamma waves have been associated with higher-level brain function, and disturbances in the patterns have been tied to schizophrenia, Alzheimer's disease, autism, epilepsy and other disorders.

Now, new research from the Salk Institute shows that little known supportive cells in the brain known as astrocytes may in fact be major players that control these waves.

In a study published July 28 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Salk researchers report a new, unexpected strategy to turn down gamma oscillations by disabling not neurons but astrocytes. In the process, the team showed that astrocytes, and the gamma oscillations they help shape, are critical for some forms of memory.

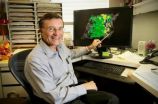

"This is what could be called a smoking gun," says co-author Terrence Sejnowski, head of the Computational Neurobiology Laboratory at the Salk Institute for Biological Sciences and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. "There are hundreds of papers linking gamma oscillations with attention and memory, but they are all correlational. This is the first time we have been able to do a causal experiment, where we selectively block gamma oscillations and show that it has a highly specific impact on how the brain interacts with the world."

A collaboration among the labs of Salk professors Sejnowski, Inder Verma and Stephen Heinemann found that activity in the form of calcium signaling in astrocytes immediately preceded gamma oscillations in the brains of mice. This suggested that astrocytes, which use many of the same chemical signals as neurons, could be influencing these oscillations.

To test their theory, the group used a virus carrying tetanus toxin to disable the release of chemicals released selectively from astrocytes, effectively eliminating the cells' ability to communicate with neighboring cells. Neurons were unaffected by the toxin.

After adding a chemical to trigger gamma waves in the animals' brains, the researchers found that brain tissue with disabled astrocytes produced shorter gamma waves than in tissue containing healthy cells. And, after adding three genes that would allow the researchers to selectively turn on and off the tetanus toxin in astrocytes at will, they found that gamma waves were dampened in mice whose astrocytes were blocked from signaling. Turning off the toxin reversed this effect.

The mice with the modified astrocytes seemed perfectly healthy. But after several cognitive tests, the researchers found that they failed in one major area: novel object recognition. As expected, healthy mouse spent more time with a new item placed in its environment than it did with familiar items. In contrast, the group's new mutant mouse treated all objects the same.

"That turned out to be a spectacular result in the sense that novel object recognition memory was not just impaired, it was gone—as if we were deleting this one form of memory, leaving others intact," Sejnowski says.

The results were surprising, in part because astrocytes operate on a seconds- or longer timescale whereas neurons signal far faster, on the millisecond scale. Because of that slower speed, no one suspected astrocytes were involved in the high-speed brain activity needed to make quick decisions.

"What I thought quite unique was the idea that astrocytes, traditionally considered only guardians and supporters of neurons and other cells, are also involved in the processing of information and in other cognitive behavior," says Verma, a professor in the Laboratory of Genetics and American Cancer Society Professor.

It's not that astrocytes are quick—they're still slower than neurons. But the new evidence suggests that astrocytes are actively supplying the right environment for gamma waves to occur, which in turn makes the brain more likely to learn and change the strength of its neuronal connections.

Sejnowski says that the behavioral result is just the tip of the iceberg. "The recognition system is hugely important," he says, adding that it includes recognizing other people, places, facts and things that happened in the past. With this new discovery, scientists can begin to better understand the role of gamma waves in recognition memory, he adds.

INFORMATION:

Collaborators included Hosuk Sean Lee of the Department of Life Sciences in Sogang University in Seoul, South Korea; Andrea Ghetti, Gustavo Dziewczapolski and Juan C. Piña-Crespo of the Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory at Salk; António Pinto-Duarte of the Institute of Pharmacology and Neurosciences, Faculty of Medicine and the Institute of Molecular Medicine Neurosciences Unit at the University of Lisbon in Portugal; Xin Wang of Salk's Computational Neurobiology Laboratory; Francesco Galimi of Salk and the Department of Biomedical Sciences/Istituto Nazionale di Biostrutture e Biosistemi, University of Sassari Medical School in Sassari, Italy; and Salvador Huitron-Resendiz and Amanda J. Roberts of the Mouse Behavioral Assessment Core at the Scripps Research Institute, in La Jolla, California.

The work was supported by a Salk Innovation Grant, Kavli Innovative Research Awards, a Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Fellowship, a Life Sciences Research Foundation Pfizer Fellowship, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Bundy Foundation, Jose Carreras International Leukemia Foundation, the Pew Charitable Trusts, National Science Foundation, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Office of Naval Research, and the National Institutes of Health.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, MD, the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Memory relies on astrocytes, the brain's lesser known cells

Salk scientists show that the little-known supportive cells are vital in cognitive function

2014-07-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists discover genetic switch that can prevent peripheral vascular disease in mice

2014-07-28

Millions of people in the United States have a circulatory problem of the legs called peripheral vascular disease. It can be painful and may even require surgery in serious cases. This disease can lead to severe skeletal muscle wasting and, in turn, limb amputation.

At The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) Medical School, scientists tested a non-surgical preventative treatment in a mouse model of the disease and it was associated with increased blood circulation. Their proof-of-concept study appears in the journal Cell Reports.

Unlike ...

Mineral magic? Common mineral capable of making and breaking bonds

2014-07-28

TEMPE, Ariz. - Reactions among minerals and organic compounds in hydrothermal environments are critical components of the Earth's deep carbon cycle, they provide energy for the deep biosphere, and may have implications for the origins of life. However, very little is known about how minerals influence organic reactions. A team of researchers from Arizona State University have demonstrated how a common mineral acts as a catalysts for specific hydrothermal organic reactions – negating the need for toxic solvents or expensive reagents.

At the heart of organic chemistry, ...

Forced mutations doom HIV

2014-07-28

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Fifteen years ago, MIT professor John Essigmann and colleagues from the University of Washington had a novel idea for an HIV drug. They thought if they could induce the virus to mutate uncontrollably, they could force it to weaken and eventually die out — a strategy that our immune system uses against many viruses.

The researchers developed such a drug, which caused HIV to mutate at an enhanced rate, as expected. But it did not eliminate the virus from patients in a small clinical trial reported in 2011. In a new study, however, Essigmann and colleagues ...

Tennessee Surgical Quality Collaborative saves 533 lives and $75 million in 3 years

2014-07-28

NEW YORK (July 28, 2:45 pm [ET]): Ten hospitals in the Tennessee Surgical Quality Collaborative (TSQC) have reduced surgical complications by 19.7 percent since 2009, resulting in at least 533 lives saved and $75.2 million in reduced costs, according to new results presented today at the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP®) National Conference in New York City.

The hospital collaborative was formed in 2008 as a partnership of the Tennessee Chapter of the American College of Surgeons and the Tennessee Hospital Association's ...

Stimulation of brain region restores consciousness to animals under general anesthesia

2014-07-28

Stimulating one of two dopamine-producing regions in the brain was able to arouse animals receiving general anesthesia with either isoflurane or propofol. In the August issue of Anesthesiology, investigators from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) report that rats anesthetized with continuous doses of either agent would move, raise their heads and even stand up in response to electrical stimulation delivered to the ventral tegmental area (VTA). Stimulation of the other major dopamine-releasing area, the substantia nigra, did not induce the animals to wake up.

"Dopamine ...

Study suggests disruptive effects of anesthesia on brain cell connections are temporary

2014-07-28

A study of juvenile rat brain cells suggests that the effects of a commonly used anesthetic drug on the connections between brain cells are temporary.

The study, published in this week's issue of the journal PLOS ONE, was conducted by biologists at the University of California, San Diego and Weill Cornell Medical College in New York in response to concerns, arising from multiple studies on humans over the past decade, that exposing children to general anesthetics may increase their susceptibility to long-term cognitive and behavioral deficits, such as learning disabilities.

An ...

UTSW cancer researchers identify irreversible inhibitor for KRAS gene mutation

2014-07-28

DALLAS – July 28, 2014 – UT Southwestern Medical Center cancer researchers have found a molecule that selectively and irreversibly interferes with the activity of a mutated cancer gene common in 30 percent of tumors.

The molecule, SML-8-73-1 (SML), interferes with the KRAS gene, or Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog. The gene produces proteins called K-Ras that influence when cells divide. Mutations in K-Ras can result in normal cells dividing uncontrollably and turning cancerous. These mutations are particularly found in cancers of the lung, pancreas, and colon. ...

Stress-tolerant tomato relative sequenced

2014-07-28

The genome of Solanum pennellii, a wild relative of the domestic tomato, has been published by an international group of researchers including the labs headed by Professors Neelima Sinha and Julin Maloof at the UC Davis Department of Plant Biology. The new genome information may help breeders produce tastier, more stress-tolerant tomatoes.

The work, published July 27 in the journal Nature Genetics, was lead by Björn Usadel and colleagues at Aachen University in Germany. The UC Davis labs carried out work on the transcriptome of S. pennellii — the RNA molecules that are ...

Researchers discover cool-burning flames in space, could lead to better engines on earth

2014-07-28

A team of international researchers has discovered a new type of cool burning flames that could lead to cleaner, more efficient engines for cars. The discovery was made during a series of experiments on the International Space Station by a team led by Forman Williams, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University of California, San Diego. Researchers detailed their findings recently in the journal Microgravity Science and Technology.

"We observed something that we didn't think could exist," Williams said.

A better understanding of the cool flames' ...

HIV research findings made possible by a test developed at CU School of Pharmacy

2014-07-28

HIV research findings made possible by a test developed at University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences (CU School of Pharmacy)

AURORA, Colo (July 28, 2014) An influential new test, discovered and developed in the Colorado Antiviral Pharmacology Laboratory at the CU School of Pharmacy, helps monitor the effectiveness of the HIV prevention drug called Truvada (a combination of tenofovir/emtricitabine), which is taken once daily to prevent HIV infection.

A study presented during the AIDS 2014 Conference and published in Lancet Infectious ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Memory relies on astrocytes, the brain's lesser known cellsSalk scientists show that the little-known supportive cells are vital in cognitive function