(Press-News.org) Cold Spring Harbor, NY -- Researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) have discovered a new function of the body's most important tumor-suppressing protein. Called p53, this protein has been called "the guardian of the genome." It normally comes to the fore when healthy cells sense damage to their DNA caused by stress, such as exposure to toxic chemicals or intense exposure to the sun's UV rays. If the damage is severe, p53 can cause a cell to commit preprogrammed cell-death, or apoptosis. Mutant versions of p53 that no longer perform this vital function, on the other hand, are enablers of many different cancers.

Cancer researcher Dr. Raffaella Sordella, a CSHL Associate Professor, and colleagues, today report in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences the discovery of a p53 cousin they call p53-psi (the Greek letter "psi"). It is a previously unknown variant of the p53 protein, generated by the same gene, called TP53 in humans, that gives rise to other forms of p53.

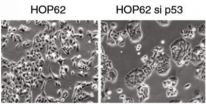

Sordella and colleagues observed that p53-psi, when expressed, reduces the expression of a molecular glue called E-cadherin, which normally keeps cells in contact within epithelial tissue, the tissue that forms the lining of the lung and many other body organs. This is accompanied by expression of key cellular markers associated with tumor invasiveness and metastatic potential. (These are markers of EMT, or epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition.) Consistently, Sordella and her team found levels of p53-psi to be elevated in early-stage lung tumors with poor prognosis.

Careful investigation revealed that p53-psi generates pro-growth effects by interacting with a protein called cyclophillin D (CypD), at the membrane of the cell's energy factories, the mitochondria, and by spurring the generation of oxidizing molecules called reactive oxygen species (ROS).

p53-psi was found by the team to be inherently expressed in tumors but also in injured tissue. "This is intriguing," Sordella says, "because generation of cells bearing characteristics of those seen in wound healing has been seen previously, in tumors."

It is possible, Sordella says, that more familiar p53 mutants associated with tumor growth and metastasis may have "hijacked" those abilities from the program used by p53-psi; to promote healing during tissue injury. A cellular program, in other words, that evolved over eons to heal may have been hijacked by mutant p53 to enable cancers to spread out of control.

The team is currently investigating p53-psi in wound healing to help clarify its role. Confirmation would lend support to the theory that mutant p53 hijacks that function to help advance pro-metastatic processes in cancer.

INFORMATION:The research discussed in this release was funded by a grant from the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation.

"p53-psi is a transcriptionally inactive p53 isoform able to reprogram cells toward a metastatic-like state" appears online ahead of print the week of July 28, 2014 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The authors are: Serif Senturk, Zhan Yao, Matthew Camiolo, Brendon Stiles, Trushar Rathod, Alice M. Walsh, Alice Nemajerova, Matthew J. Lazzara, Nasser K. Altorki, Adrian Krainer, Ute M. Moll, Scott W. Lowe, Luca Cartegni and Raffaella Sordella. The paper can be obtained at: http://www.pnas.org/content/early/recent

About Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Founded in 1890, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has shaped contemporary biomedical research and education with programs in cancer, neuroscience, plant biology and quantitative biology. CSHL is ranked number one in the world by Thomson Reuters for the impact of its research in molecular biology and genetics. The Laboratory has been home to eight Nobel Prize winners. Today, CSHL's multidisciplinary scientific community is more than 600 researchers and technicians strong and its Meetings & Courses program hosts more than 12,000 scientists from around the world each year to its Long Island campus and its China center. For more information, visit http://www.cshl.edu.

Research may explain how foremost anticancer 'guardian' protein learned to switch sides

2014-07-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study: Pediatric preventive care guidelines need retooling for computerized format

2014-07-29

INDIANAPOLIS -- With the increasing use of electronic medical records and health information exchange, there is a growing demand for a computerized version of the preventive care guidelines pediatricians use across the United States. In a new study, researchers from the Indiana University School of Medicine and the Regenstrief Institute report that substantial work lies ahead to convert the American Academy of Pediatrics' Bright Future's guidelines into computerized prompts for physicians, but the payoff has the potential to significantly benefit patients from birth to ...

Menu secrets that can make you slim by design

2014-07-29

If you've ever ordered the wrong food at a restaurant, don't blame yourself; blame the menu. What you order may have less to do with what you want and more to do with a menu's layout and descriptions.

After analyzing 217 menus and the selections of over 300 diners, the Cornell study published this month in the International Journal of Hospitality Management showed that when it comes to what you order for dinner, two things matter most: what you see on the menu and how you imagine it will taste.

First, any food item that attracts attention (with bold, hightlighted or ...

From 'Finding Nemo' to minerals -- what riches lie in the deep sea?

2014-07-29

As fishing and the harvesting of metals, gas and oil have expanded deeper and deeper into the ocean, scientists are drawing attention to the services provided by the deep sea, the world's largest environment. "This is the time to discuss deep-sea stewardship before exploitation is too much farther underway," says lead-author Andrew Thurber. In a review published today in Biogeosciences, a journal of the European Geosciences Union (EGU), Thurber and colleagues summarise what this habitat provides to humans, and emphasise the need to protect it.

"The deep sea realm is so ...

Genomic analysis of prostate cancer indicates best course of action after surgery

2014-07-29

(PHILADELPHIA) – There is controversy over how best to treat patients after they've undergone surgery for prostate cancer. Does one wait until the cancer comes back or provide men with additional radiation therapy to prevent cancer recurrence? Now, a new study from Thomas Jefferson University shows that a genomic tool can help doctors and patients make a more informed decision.

"We are moving away from treating everyone the same," says first author Robert Den, M.D., Assistant Professor of Radiation Oncology and Cancer Biology at Thomas Jefferson University. "Genomic ...

Optimum inertial self-propulsion design for snowman-like nanorobot

2014-07-29

Scale plays a major role in locomotion. Swimming microorganisms, such as bacteria and spermatozoa, are subjected to relatively small inertial forces compared to the viscous forces exerted by the surrounding fluid. Such low-level inertia makes self-propulsion a major challenge. Now, scientists have found that the direction of propulsion made possible by such inertia is opposite to that induced by a viscoelastic fluid. These findings have been published in EPJ E by François Nadal from the Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), in Le Barp, France, and colleagues. ...

Team studies the social origins of intelligence in the brain

2014-07-29

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — By studying the injuries and aptitudes of Vietnam War veterans who suffered penetrating head wounds during the war, scientists are tackling -- and beginning to answer -- longstanding questions about how the brain works.

The researchers found that brain regions that contribute to optimal social functioning also are vital to general intelligence and to emotional intelligence. This finding bolsters the view that general intelligence emerges from the emotional and social context of one's life.

The findings are reported in the journal Brain.

"We are ...

NOAA: Alaska fisheries and communities at risk from ocean acidification

2014-07-29

Ocean acidification is driving changes in waters vital to Alaska's valuable commercial fisheries and subsistence way of life, according to new NOAA-led research that will be published online in Progress in Oceanography.

Many of Alaska's nutritionally and economically valuable marine fisheries are located in waters that are already experiencing ocean acidification, and will see more in the near future, the study shows. Communities in southeast and southwest Alaska face the highest risk from ocean acidification because they rely heavily on fisheries that are expected to ...

Preterm children's brains can catch up years later

2014-07-29

There's some good news for parents of preterm babies – latest research from the University of Adelaide shows that by the time they become teenagers, the brains of many preterm children can perform almost as well as those born at term.

A study conducted by the University's Robinson Research Institute has found that as long as the preterm child experiences no brain injury in early life, their cognitive abilities as a teenager can potentially be as good as their term-born peers.

However, the results of the study, published in this month's issue of The Journal of Pediatrics, ...

New anesthesia technique helps show cause of obstruction in sleep apnea

2014-07-29

July 29, 2014 – A simplified anesthesia procedure may enable more widespread use of preoperative testing to demonstrate the cause of airway obstruction in patients with severe sleep apnea, suggests a study in Anesthesia & Analgesia.

Dr. Joshua H. Atkins and Dr. Jeff E. Mandel of the University of Pennsylvania and their colleagues have developed a new "ramp control" anesthetic technique for putting patients to sleep briefly-just enough to show the "obstructive anatomy" responsible for sleep apnea. The simplified technique requires no special expertise and limits drops ...

Mysterious esophagus disease is autoimmune after all

2014-07-29

Achalasia is a rare disease – it affects 1 in 100,000 people – characterized by a loss of nerve cells in the esophageal wall. While its cause remains unknown, a new study by a team of researchers at KU Leuven in Belgium, the University of Bonn in Germany and other European institutions confirms for the first time that achalasia is autoimmune in origin. The study, published on 6 July in Nature Genetics, is an important step towards unraveling the mysterious disease.

When we swallow, a sphincter in the lower esophagus opens, allowing food to enter the stomach. Nerve cells ...