(Press-News.org) Media and marketing experts have long sought a reliable method of forecasting responses from the general population to future products and messages. According to a study conducted at the City College of New York (CCNY) in partnership with Georgia Tech, it appears that the brain responses of just a few individuals are a remarkably strong predictor.

By analyzing the brainwaves of 16 individuals as they watched mainstream television content, researchers were able to accurately predict the preferences of large TV audiences, up to 90 percent in the case of Super Bowl commercials. The findings appear in a paper entitled "Audience Preferences Are Predicted by Temporal Reliability of Neural Processing," which was just published in the latest edition of Nature Communications.

"Alternative methods such as self-reports are fraught with problems as people conform their responses to their own values and expectations," said Jacek Dmochowski, lead author of the paper and a postdoctoral fellow at CCNY at the time the study was being conducted. However, brain signals measured using electroencephalography (EEG) can, in principle, alleviate this shortcoming by providing immediate physiological responses immune to such self-biasing. "Our findings show that these immediate responses are in fact closely tied to the subsequent behavior of the general population," he added.

Lucas Parra, Herbert Kayser Professor of Biomedical Engineering at CCNY and the paper's senior author explained that, "when two people watch a video, their brains respond similarly – but only if the video is engaging. Popular shows and commercials draw our attention and make our brainwaves very reliable; the audience is literally 'in-sync'."

In the study, participants watched scenes from The Walking Dead TV show and several commercials from the 2012 and 2013 Super Bowls. EEG electrodes were placed on their heads to capture brain activity. The reliability of the recorded neural activity was then compared to audience reactions in the general population using publicly available social media data provided by the Harmony Institute and ratings from USA Today's Super Bowl Ad Meter.

"Brain activity among our participants watching The Walking Dead predicted 40 percent of the associated Twitter traffic," said Parra. "When brainwaves were in agreement, the number of tweets tended to increase." Brainwaves also predicted 60 percent of the Nielsen ratings that measure the size of a TV audience.

The study was even more accurate (90 percent) when comparing preferences for Super Bowl ads. For instance, researchers saw very similar brainwaves from their participants as they watched a 2012 Budweiser commercial that featured a beer-fetching dog. The general public voted the ad as their second favorite that year. The study found little agreement in the brain activity among participants when watching a GoDaddy commercial featuring a kissing couple. It was among the worst rated ads in 2012.

The CCNY researchers collaborated with Matthew Bezdek and Eric Schumacher from Georgia Tech to identify which brain regions are involved and explain the underlying mechanisms. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), they found evidence that brainwaves for engaging ads could be driven by activity in visual, auditory and attention brain areas.

"Interesting ads may draw our attention and cause deeper sensory processing of the content," said Bezdek, a postdoctoral researcher at Georgia Tech's School of Psychology.

Apart from applications to marketing and film, Parra is investigating whether this measure of attentional draw can be used to diagnose neurological disorders such as attention deficit disorder or mild cognitive decline. Another potential application is to predict the effectiveness of online educational videos by measuring how engaging they are.

INFORMATION:

CCNY Interviews:

Lucas Parra

626-864-9390

parra@ccny.cuny.edu

Georgia Tech Interviews

Jason Maderer

404-385-2966

maderer@gatech.edu

Brainwaves can predict audience reaction for television programming

2014-07-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Socialization relative strength in fragile X longitudinal study

2014-07-29

Standard scores measuring "adaptive behavior" in boys with fragile X syndrome tend to decline during childhood and adolescence, the largest longitudinal study of the inherited disorder to date has found.

Adaptive behavior covers a range of everyday social and practical skills, including communication, socialization, and completing tasks of daily living such as getting dressed. In this study, socialization emerged as a relative strength in boys with fragile X, in that it did not decline as much as the other two domains of adaptive behavior measured: communication and daily ...

Brand-specific television alcohol ads predict brand consumption among underage youth

2014-07-29

Underage drinkers are three times more likely to drink alcohol brands that advertise on television programs they watch compared to other alcohol brands, providing new and compelling evidence of a strong association between alcohol advertising and youth drinking behavior.

This is the conclusion of a new study from the Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth (CAMY) at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Boston University School of Public Health that examined whether exposure to brand-specific alcohol advertising on 20 television shows popular with ...

$15 billion annual public funding system for doctor training needs overhaul, says IOM

2014-07-29

WASHINGTON -- The U.S. should significantly reform the federal system for financing physician training and residency programs to ensure that the public's $15 billion annual investment is producing the doctors that the nation needs, says a new report by the Institute of Medicine. Current financing -- provided largely through Medicare -- requires little accountability, allocates funds independent of workforce needs or educational outcomes, and offers insufficient opportunities to train physicians in the health care settings used by most Americans, the report says.

All ...

A new way to make microstructured surfaces

2014-07-29

A team of researchers has created a new way of manufacturing microstructured surfaces that have novel three-dimensional textures. These surfaces, made by self-assembly of carbon nanotubes, could exhibit a variety of useful properties — including controllable mechanical stiffness and strength, or the ability to repel water in a certain direction.

"We have demonstrated that mechanical forces can be used to direct nanostructures to form complex three-dimensional microstructures, and that we can independently control … the mechanical properties of the microstructures," says ...

NASA sees warmer cloud tops as Tropical Storm Hernan degenerates

2014-07-29

Tropical Storm Hernan degenerated into a remnant low pressure area on July 29. Infrared imagery from NASA's Aqua satellite revealed cloud tops were warming as the storm weakened.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument aboard Aqua gathered infrared data on a quickly weakening Hernan on July 29 at 5:11 a.m. EDT. The data was then made into a false-colored image at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. The AIRS image showed small, fragmented areas of a few powerful thunderstorms with high, cold cloud tops in Tropical Storm Hernan as it continued ...

Superconductivity could form at high temperatures in layered 2-D crystals

2014-07-29

An elusive state of matter called superconductivity could be realized in stacks of sheetlike crystals just a few atoms thick, a trio of physicists has determined.

Superconductivity, the flow of electrical current without resistance, is usually found in materials chilled to the most frigid temperatures, which is impractical for most applications. It's been observed at higher temperatures–higher being about 100 kelvin or minus 280 degrees below zero Fahrenheit–in copper oxide materials called cuprate superconductors. But those materials are brittle and unsuitable for fabricating ...

Autistic brain less flexible at taking on tasks, Stanford study shows

2014-07-29

The brains of children with autism are relatively inflexible at switching from rest to task performance, according to a new brain-imaging study from the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Instead of changing to accommodate a job, connectivity in key brain networks of autistic children looks similar to connectivity in the resting brain. And the greater this inflexibility, the more severe the child's manifestations of repetitive and restrictive behaviors that characterize autism, the study found.

The study, which will be published online July 29 in Cerebral Cortex, ...

Diet affects men's and women's gut microbes differently

2014-07-29

The microbes living in the guts of males and females react differently to diet, even when the diets are identical, according to a study by scientists from The University of Texas at Austin and six other institutions published this week in the journal Nature Communications. These results suggest that therapies designed to improve human health and treat diseases through nutrition might need to be tailored for each sex.

The researchers studied the gut microbes in two species of fish and in mice, and also conducted an in-depth analysis of data that other researchers collected ...

Scientists separate a particle from its properties

2014-07-29

Researchers from the Vienna University of Technology have performed the first separation of a particle from one of its properties. The study, carried out at the Institute Laue-Langevin (ILL) and published in Nature Communications, showed that in an interferometer a neutron's magnetic moment could be measured independently of the neutron itself, thereby marking the first experimental observation of a new quantum paradox known as the 'Cheshire Cat'. The new technique, which can be applied to any property of any quantum object, could be used to remove disturbance and improve ...

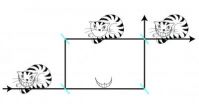

The quantum Cheshire cat: Scientists separate a particle from its properties

2014-07-29

The Quantum Cheshire Cat: Can a particle be separated from its properties? On July 29, the prestigious journal, Nature Communications, published the results of the first Cheshire Cat experiment, separating a neutron from its magnetic field, conducted by Chapman University in Orange, CA, and Vienna University of Technology.

Chesire Cat"Well! I've often seen a cat without a grin," thought Alice in Wonderland, "but a grin without a cat! It's the most curious thing I ever saw in my life!" Alice's surprise stems from her experience that an object and its property cannot exist ...