(Press-News.org) The brains of children with autism are relatively inflexible at switching from rest to task performance, according to a new brain-imaging study from the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Instead of changing to accommodate a job, connectivity in key brain networks of autistic children looks similar to connectivity in the resting brain. And the greater this inflexibility, the more severe the child's manifestations of repetitive and restrictive behaviors that characterize autism, the study found.

The study, which will be published online July 29 in Cerebral Cortex, used functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, to examine children's brain activity at rest and during two tasks: solving simple math problems and looking at pictures of different faces. The study included an equal number of children with and without autism. The developmental disorder, which now affects one of every 68 children in the United States, is characterized by social and communication deficits, repetitive behaviors and sensory problems.

"We wanted to test the idea that a flexible brain is necessary for flexible behaviors," said Lucina Uddin, PhD, a lead author of the study. "What we found was that across a set of brain connections known to be important for switching between different tasks, children with autism showed reduced 'brain flexibility' compared with typically developing peers." Uddin, who is now an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Miami, was a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford when the research was conducted.

"The fact that we can tie this neurophysiological brain-state inflexibility to behavioral inflexibility is an important finding because it gives us clues about what kinds of processes go awry in autism," said Vinod Menon, PhD, the Rachel L. and Walter F. Nichols, MD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford and the senior author of the study.

The researchers focused on a network of brain areas they have studied before. These areas are involved in making decisions, performing social tasks and identifying relevant events in the environment to guide behavior. The team's prior work showed that, in children with autism, activity in these areas was more tightly connected when the brain was at rest than it was in children who didn't have autism.

The new research shows that, in autism, connectivity in these networks that can be seen on fMRI scans is fairly similar regardless of whether the brain is at rest or performing a task. In contrast, typically developing children have a larger shift in brain connectivity when they perform tasks.

The study looked at 34 kids with autism and 34 typically developing children. All of the children with autism received standard clinical evaluations to characterize the severity of their disorder. Then, the two groups were split in half: 17 children with autism and 17 typically developing children had their brains scanned with fMRI while at rest and while performing simple arithmetic problems. The remaining children had their brains scanned at rest and during a task that asked them to distinguish between different people's faces. The facial recognition task was chosen because autism is characterized by social deficits; the math task was chosen to reflect an area in which children with autism do not usually have deficits.

Children with autism performed as well as their typically developing peers on both tasks — that is, they were as good at distinguishing between the faces and solving the math problems. However, their brain scan results were different. In addition to the reduced brain flexibility, the researchers showed a correlation between the degree of inflexibility and the severity of restrictive and repetitive behaviors, such as performing the same routine over and over or being obsessed with a favorite topic.

"This is the first study that has examined how the patterns of intrinsic brain connectivity change with a cognitive load in children with autism," Menon said. The research is the first to demonstrate that brain connectivity in children with autism changes less, relative to rest, in response to a task than the brains of other children, he added.

"The findings may help researchers evaluate the effects of different autism therapies," said Kaustubh Supekar, PhD, a research associate and the other lead author of the study. "Therapies that increase the brain's flexibility at switching from rest to goal-directed behaviors may be a good target, for instance."

"We're making progress in identifying a brain basis of autism, and we're starting to get traction in pinpointing systems and signaling mechanisms that are not functioning properly," Menon said. "This is giving us a better handle both in thinking about treatment and in looking at change or plasticity in the brain."

INFORMATION:

Other Stanford authors of the study are research assistants Charles Lynch, Katherine Cheng, Paola Odriozola and Maria Barth; Jennifer Phillips, PhD, clinical associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and co-director of the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Clinic at Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford; Carl Feinstein, MD, professor emeritus of psychiatry and behavioral sciences; and Daniel Abrams, PhD, postdoctoral scholar.

Feinstein and Menon are members of Stanford's Child Health Research Institute.

The study was supported by grants from the International Society for Autism Research, the Singer Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health (grants K01MH092288, HD047520, HD059205 and MH084164).

Information about Stanford's Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, which also supported the work, is available at http://psychiatry.stanford.edu.

The Stanford University School of Medicine consistently ranks among the nation's top medical schools, integrating research, medical education, patient care and community service. For more news about the school, please visit http://mednews.stanford.edu. The medical school is part of Stanford Medicine, which includes Stanford Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford. For information about all three, please visit http://stanfordmedicine.org/about/news.html.

Autistic brain less flexible at taking on tasks, Stanford study shows

2014-07-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Diet affects men's and women's gut microbes differently

2014-07-29

The microbes living in the guts of males and females react differently to diet, even when the diets are identical, according to a study by scientists from The University of Texas at Austin and six other institutions published this week in the journal Nature Communications. These results suggest that therapies designed to improve human health and treat diseases through nutrition might need to be tailored for each sex.

The researchers studied the gut microbes in two species of fish and in mice, and also conducted an in-depth analysis of data that other researchers collected ...

Scientists separate a particle from its properties

2014-07-29

Researchers from the Vienna University of Technology have performed the first separation of a particle from one of its properties. The study, carried out at the Institute Laue-Langevin (ILL) and published in Nature Communications, showed that in an interferometer a neutron's magnetic moment could be measured independently of the neutron itself, thereby marking the first experimental observation of a new quantum paradox known as the 'Cheshire Cat'. The new technique, which can be applied to any property of any quantum object, could be used to remove disturbance and improve ...

The quantum Cheshire cat: Scientists separate a particle from its properties

2014-07-29

The Quantum Cheshire Cat: Can a particle be separated from its properties? On July 29, the prestigious journal, Nature Communications, published the results of the first Cheshire Cat experiment, separating a neutron from its magnetic field, conducted by Chapman University in Orange, CA, and Vienna University of Technology.

Chesire Cat"Well! I've often seen a cat without a grin," thought Alice in Wonderland, "but a grin without a cat! It's the most curious thing I ever saw in my life!" Alice's surprise stems from her experience that an object and its property cannot exist ...

The quantum Cheshire cat

2014-07-29

The Cheshire Cat featured in Lewis Caroll's novel "Alice in Wonderland" is a remarkable creature: it disappears, leaving its grin behind. Can an object be separated from its properties? It is possible in the quantum world. In an experiment, neutrons travel along a different path than one of their properties – their magnetic moment. This "Quantum Cheshire Cat" could be used to make high precision measurements less sensitive to external perturbations.

At Different Places at Once

According to the law of quantum physics, particles can be in different physical states at ...

Major turtle nesting beaches protected in 1 of the UK's far flung overseas territories

2014-07-29

But on the remote UK overseas territory of Ascension Island, one of the world's largest green turtle populations is undergoing something of a renaissance.

Writing in the journal Biodiversity and Conservation, scientists from the University of Exeter and Ascension Island Government Conservation Department report that the number of green turtles nesting at the remote South Atlantic outpost has increased by more than 500 per cent since records began in the 1970s. As many as 24,000 nests are now estimated to be laid on the Island's main beaches every year, making it the second ...

Could summer camp be the key to world peace?

2014-07-29

According to findings from a new study by University of Chicago Booth School of Business Professor Jane Risen, and Chicago Booth doctoral student Juliana Schroeder, it may at least be a start.

Risen and Schroeder conducted research on Seeds of Peace, one of the largest peacebuilding programs that brings together teenagers from conflict regions, including Israelis and Palestinians, every year for three weeks in rural Maine. They tracked participants' feelings and attitudes toward the other national group for three years with three separate cohorts of campers. They found ...

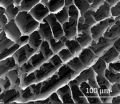

Tough foam from tiny sheets

2014-07-29

HOUSTON – (July 29, 2014) – Tough, ultralight foam of atom-thick sheets can be made to any size and shape through a chemical process invented at Rice University.

In microscopic images, the foam dubbed "GO-0.5BN" looks like a nanoscale building, with floors and walls that reinforce each other. The structure consists of a pair of two-dimensional materials: floors and walls of graphene oxide that self-assemble with the assistance of hexagonal boron nitride platelets.

The researchers say the foam could find use in structural components, as supercapacitor and battery electrodes ...

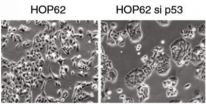

Research may explain how foremost anticancer 'guardian' protein learned to switch sides

2014-07-29

Cold Spring Harbor, NY -- Researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) have discovered a new function of the body's most important tumor-suppressing protein. Called p53, this protein has been called "the guardian of the genome." It normally comes to the fore when healthy cells sense damage to their DNA caused by stress, such as exposure to toxic chemicals or intense exposure to the sun's UV rays. If the damage is severe, p53 can cause a cell to commit preprogrammed cell-death, or apoptosis. Mutant versions of p53 that no longer perform this vital function, on the ...

Study: Pediatric preventive care guidelines need retooling for computerized format

2014-07-29

INDIANAPOLIS -- With the increasing use of electronic medical records and health information exchange, there is a growing demand for a computerized version of the preventive care guidelines pediatricians use across the United States. In a new study, researchers from the Indiana University School of Medicine and the Regenstrief Institute report that substantial work lies ahead to convert the American Academy of Pediatrics' Bright Future's guidelines into computerized prompts for physicians, but the payoff has the potential to significantly benefit patients from birth to ...

Menu secrets that can make you slim by design

2014-07-29

If you've ever ordered the wrong food at a restaurant, don't blame yourself; blame the menu. What you order may have less to do with what you want and more to do with a menu's layout and descriptions.

After analyzing 217 menus and the selections of over 300 diners, the Cornell study published this month in the International Journal of Hospitality Management showed that when it comes to what you order for dinner, two things matter most: what you see on the menu and how you imagine it will taste.

First, any food item that attracts attention (with bold, hightlighted or ...