(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

These are time-lapse videos of Caenorhabditis hermaphrodites that were (A) mated with the same species and (B) mated with a different species. Male sperm were fluorescently labeled and appear as...

Click here for more information.

The classic definition of a biological species is the ability to breed within its group, and the inability to breed outside it. For instance, breeding a horse and a donkey may result in a live mule offspring, but mules are nearly always sterile due to genomic incompatibility between the two species.

The vast majority of the time, mating across species is merely unsuccessful in producing offspring. However, when researchers at the University of Maryland and the University of Toronto mated Caenorhabditis worms of different species, they found that the lifespan of the female worms and their number of progeny were drastically reduced compared with females that mated with the same species. In addition, females that survived cross-species mating were often sterile, even if they subsequently mated with their own species.

When the researchers observed the sterile and dying female worms under a microscope using a fluorescent stain to visualize sperm in live worms, they discovered that the foreign sperm had broken through the sphincter of the worm's uterus and invaded the ovaries. There, the sperm prematurely fertilized the eggs, which were then unable to develop into viable offspring. The sperm eventually destroyed the ovaries, resulting in sterility. The sperm then traveled farther throughout the worm's body, resulting in tissue damage and death.

"Our findings were quite surprising because females typically just select sperm from males of their own species during fertilization, an action that does not lead to long-term consequences because there is no gene flow between the species," said Asher Cutter, associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Toronto.

The results suggest the interaction between sperm and the female reproductive tract as a novel reason for failed mating in worms, noted Eric Haag, associate professor of biology at UMD. "The findings may be worth investigating in other species as well, because similar coordination problems may be relevant to infertility in other organisms," he added.

The study, which was led by graduate students Gavin Woodruff from UMD and Janice Ting from the University of Toronto, was published on July 29, 2014 in the journal PLOS Biology. Woodruff is now a postdoctoral researcher at the Forestry and Forest Research Products Institute in Japan.

The researchers believe the "killer sperm" may be the result of a divergence in the evolution of worm species' sexual organs—in particular, the ability of sperm to physically compete with one another. When a female worm mates with multiple males, the sperm jostle each other, competing for access to the eggs. Female worms' bodies must be able to withstand this competition to survive and produce offspring. The researchers hypothesize that the aggressiveness of the sperm and the ability of the uterus to tolerate the sperm are the same within a single species, but not across multiple species. Thus, a female from a species with less active sperm may not be able to tolerate the aggressive sperm from a different species.

There is evidence for this theory. In the current study, three species of hermaphrodite worms—which produce their own sperm and fertilize their own eggs to reproduce—were especially susceptible to sterility and death when mated with males of other species. The hermaphrodite uterus may have evolved to tolerate "gentler" sperm, but not the larger, more active sperm of non-hermaphrodite species, according to the researchers.

"We found that hermaphrodites can sense, and try to avoid, males of species that can harm them," added Haag.

This instance of lethal cross-species mating is of special interest to evolutionary biologists, Haag notes, because it's unclear how the many species on earth -- 8.7 million, not counting bacteria, according to an estimate published in Nature—remain distinct from each other.

"Punishing cross-species mating by sterility or death would be a powerful evolutionary way to maintain a species barrier," Haag said.

However, evolution usually leaves a few survivors behind, even in the most adverse conditions. The researchers had previously found that the harmful crosses between species nevertheless can produce a few viable offspring. Haag plans to follow up on this study by investigating how these hybrid worms behave when they are bred to different species.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Award No. GM79414) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. The content of this article does not necessarily reflect the views of these organizations.

Eric Haag Laboratory: http://www.life.umd.edu/biology/haag/

Asher Cutter Laboratory: http://labs.eeb.utoronto.ca/cutter/

The research paper "Intense Sperm-mediated Sexual Conflict Promotes Reproductive Isolation in Caenorhabditis Nematodes," Janice J. Ting, Gavin C. Woodruff, Gemma Leung, Na-Ra Shin, Asher D. Cutter & Eric S. Haag, was published online July 29, 2014 in PLOS Biology, http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001915.

Writer: Irene Ying

About the College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

The College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences at the University of Maryland educates more than 7,000 future scientific leaders in its undergraduate and graduate programs each year. The college's 10 departments and more than a dozen interdisciplinary research centers foster scientific discovery with annual sponsored research funding exceeding $150 million. For more information, go to: http://www.cmns.umd.edu

.

'Killer sperm' prevents mating between worm species

2014-07-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Urbanization of rural Africa associated with increased risk of heart disease and diabetes

2014-07-29

The increasing urbanisation of rural areas in sub-Saharan Africa could lead to an explosion in incidences of heart disease and diabetes, according to a new study carried out in Uganda which found that even small changes towards more urban lifestyles was associated with increased risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.

Over 530 million people live in rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa, where rates of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases tend to be much lower than in urban areas. However, many of these areas are becoming increasingly urbanised, with people living ...

Mysterious molecules in space

2014-07-29

WASHINGTON D.C., July 29, 2014 – Over the vast, empty reaches of interstellar space, countless small molecules tumble quietly though the cold vacuum. Forged in the fusion furnaces of ancient stars and ejected into space when those stars exploded, these lonely molecules account for a significant amount of all the carbon, hydrogen, silicon and other atoms in the universe. In fact, some 20 percent of all the carbon in the universe is thought to exist as some form of interstellar molecule.

Many astronomers hypothesize that these interstellar molecules are also responsible ...

This week from AGU: Cell tower rain gauges, lightning channels, North Sea storm surge

2014-07-29

This Week From AGU: Cell phone tower rain gauges, lightning channels, North Sea storm surge

From AGU's blogs: Dropped cell phone calls become rain gauges in West Africa

A shaky cell phone connection during a rainstorm can be an annoying nuisance. But now scientists are showing that these weakened signals can be used to monitor rainfall in West Africa, a technique that could help cities in the region better prepare for floods and combat weather-related diseases, according to a new study accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American ...

Penn team makes cancer glow to improve surgical outcomes

2014-07-29

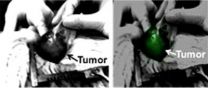

The best way to cure most cases of cancer is to surgically remove the tumor. The Achilles heel of this approach, however, is that the surgeon may fail to extract the entire tumor, leading to a local recurrence.

With a new technique, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have established a new strategy to help surgeons see the entire tumor in the patient, increasing the likelihood of a positive outcome. This approach relies on an injectable dye that accumulates in cancerous tissues much more so than normal tissues. When the surgeon shines an infrared light on the ...

Huge waves measured for first time in Arctic Ocean

2014-07-29

As the climate warms and sea ice retreats, the North is changing. An ice-covered expanse now has a season of increasingly open water which is predicted to extend across the whole Arctic Ocean before the middle of this century. Storms thus have the potential to create Arctic swell – huge waves that could add a new and unpredictable element to the region.

A University of Washington researcher made the first study of waves in the middle of the Arctic Ocean, and detected house-sized waves during a September 2012 storm. The results were recently published in Geophysical Research ...

Underwater elephants

2014-07-29

In the high-tech world of science, researchers sometimes need to get back to basics. UC Santa Barbara's Douglas McCauley did just that to study the impacts of the bumphead parrotfish (Bolbometopon muricatum) on coral reef ecosystems at two remote locations in the central Pacific Ocean.

Using direct observation, animal tracking and computer simulation, McCauley, an assistant professor in the Department of Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology, and his colleagues sought to understand whether the world's largest parrotfish is necessary for positively shaping the structure ...

Vision-correcting display makes reading glasses so yesterday

2014-07-29

BERKELEY — What if computer screens had glasses instead of the people staring at the monitors? That concept is not too far afield from technology being developed by computer and vision scientists at the University of California, Berkeley.

The researchers are developing computer algorithms to compensate for an individual's visual impairment, and creating vision-correcting displays that enable users to see text and images clearly without wearing eyeglasses or contact lenses. The technology could potentially help hundreds of millions of people who currently need corrective ...

Researchers take steps toward development of a vaccine against tick-transmitted disease

2014-07-29

Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine researchers have made an important advancement toward developing a vaccine against the debilitating and potentially deadly tick-transmitted disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA).

During the past several years, experts have seen a steady rise in the incidence of human infections caused by tick-transmitted bacterial pathogens — making the need for a vaccine critical. Successful vaccine development hinges on knowing what to target to prevent disease, and the VCU team has identified three such proteins on the surface ...

Brainwaves can predict audience reaction for television programming

2014-07-29

Media and marketing experts have long sought a reliable method of forecasting responses from the general population to future products and messages. According to a study conducted at the City College of New York (CCNY) in partnership with Georgia Tech, it appears that the brain responses of just a few individuals are a remarkably strong predictor.

By analyzing the brainwaves of 16 individuals as they watched mainstream television content, researchers were able to accurately predict the preferences of large TV audiences, up to 90 percent in the case of Super Bowl commercials. ...

Socialization relative strength in fragile X longitudinal study

2014-07-29

Standard scores measuring "adaptive behavior" in boys with fragile X syndrome tend to decline during childhood and adolescence, the largest longitudinal study of the inherited disorder to date has found.

Adaptive behavior covers a range of everyday social and practical skills, including communication, socialization, and completing tasks of daily living such as getting dressed. In this study, socialization emerged as a relative strength in boys with fragile X, in that it did not decline as much as the other two domains of adaptive behavior measured: communication and daily ...