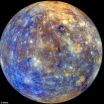

(Press-News.org) Earth and Mercury are both rocky planets with iron cores, but Mercury's interior differs from Earth's in a way that explains why the planet has such a bizarre magnetic field, UCLA planetary physicists and colleagues report.

Measurements from NASA's Messenger spacecraft have revealed that Mercury's magnetic field is approximately three times stronger at its northern hemisphere than its southern one. In the current research, scientists led by Hao Cao, a UCLA postdoctoral scholar working in the laboratory of Christopher T. Russell, created a model to show how the dynamics of Mercury's core contribute to this unusual phenomenon.

The magnetic fields that surround and shield many planets from the sun's energy-charged particles differ widely in strength. While Earth's is powerful, Jupiter's is more than 12 times stronger, and Mercury has a rather weak magnetic field. Venus likely has none at all. The magnetic fields of Earth, Jupiter and Saturn show very little difference between the planets' two hemispheres.

Within Earth's core, iron turns from a liquid to a solid at the inner boundary of the planet's liquid outer core; this results in a solid inner part and liquid outer part. The solid inner core is growing, and this growth provides the energy that generates Earth's magnetic field. Many assumed, incorrectly, that Mercury would be similar.

"Hao's breakthrough is in understanding how Mercury is different from the Earth so we could understand Mercury's strongly hemispherical magnetic field," said Russell, a co-author of the research and a professor in the UCLA College's department of Earth, planetary and space sciences. "We had figured out how the Earth works, and Mercury is another terrestrial, rocky planet with an iron core, so we thought it would work the same way. But it's not working the same way."

Mercury's peculiar magnetic field provides evidence that iron turns from a liquid to a solid at the core's outer boundary, say the scientists, whose research currently appears online in the journal Geophysical Research Letters and will be published in an upcoming print edition.

"It's like a snow storm in which the snow formed at the top of the cloud and middle of the cloud and the bottom of the cloud too," said Russell. "Our study of Mercury's magnetic field indicates iron is snowing throughout this fluid that is powering Mercury's magnetic field."

The research implies that planets have multiple ways of generating a magnetic field.

Hao and his colleagues conducted mathematical modeling of the processes that generate Mercury's magnetic field. In creating the model, Hao considered many factors, including how fast Mercury rotates and the chemistry and complex motion of fluid inside the planet.

The cores of both Mercury and Earth contain light elements such as sulfur, in addition to iron; the presence of these light elements keeps the cores from being completely solid and "powers the active magnetic field–generation processes," Hao said.

Hao's model is consistent with data from Messenger and other research on Mercury and explains Mercury's asymmetric magnetic field in its hemispheres. He said the first important step was to "abandon assumptions" that other scientists make.

"Planets are different from one another," said Hao, whose research is funded by a NASA fellowship. "They all have their individual character."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors include Jonathan Aurnou, professor of planetary science and geophysics in UCLA's Department of Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences, and Johannes Wicht, a research scientist at Germany's Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research.

Mercury's magnetic field tells scientists how its interior is different from Earth's

2014-07-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Differential gene expression in proximal and distal nerve segments after sciatic nerve injury

2014-07-30

Wallerian degeneration is a subject of major interest in neuroscience. A large number of genes are differentially regulated during the distinct stages of Wallerian degeneration: transcription factor activation, immune response, myelin cell differentiation and dedifferentiation. Although gene expression responses in the distal segment of the sciatic nerve after peripheral nerve injury are known, differences in gene expression between the proximal and distal segments remain unclear. Dr. Dengbing Yao and co-workers from Nantong University, China used microarrays to analyze ...

Implanting 125I seeds into rat DRG for neuropathic pain: Only neuronal microdamage occurs

2014-07-30

The use of iodine-125 (125I) in cancer treatment has been shown to relieve patients' pain. Considering dorsal root ganglia are critical for neural transmission between the peripheral and central nervous systems, Dr. Tengda Zhang and colleagues from Institute of Radiation Medicine, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, China assumed that 125I could be implanted into rat dorsal root ganglia (DRG) to provide relief for neuropathic pain. 125I seeds with different radioactivity (0, 14.8, 29.6 MBq) were implanted separately into the vicinity of the L5 DRG. Experimental results ...

Facilitating transparency in spinal cord injury studies using recognized information standards

2014-07-30

Progress in developing robust therapies for spinal cord injury (SCI), traumatic brain injury (TBI) and peripheral nerve injury has been slow. A great deal has been learned over the past 30 years regarding both the intrinsic factors and the environmental factors that regulate axon growth, but this large body of information has not yet resulted in clinically available therapeutics. Prof. Lemmon and his team from University of Miami in USA proposed this therapeutic bottleneck has many root causes, but a consensus is emerging that one contributing factor is a lack of standards ...

Dyscalculia: Burdened by blunders with numbers

2014-07-30

Between 3 and 6% of schoolchildren suffer from an arithmetic-related learning disability. Researchers at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet (LMU) in Munich now show that these children are also more likely to exhibit deficits in reading and spelling than had been previously suspected.

Addition and subtraction, multiplication and division are the four basic operations in arithmetic. But for some children, learning these fundamental skills is particularly challenging. Studies show that they have problems grasping the concepts of number, magnitude, and quantity, and that they ...

Older adults are at risk of financial abuse

2014-07-30

Nearly one in every twenty elderly American adults is being financially exploited – often by their own family members. This burgeoning public health crisis especially affects poor and black people. It merits the scrutiny of clinicians, policy makers, researchers, and any citizen who cares about the dignity and well-being of older Americans, says Dr. Janey Peterson of Weill Cornell Medical College in the US. She led one of the largest American studies¹ ever on elder abuse, the findings of which appear in the Journal of General Internal Medicine², published by Springer.

With ...

Sugar mimics guide stem cells toward neural fate

2014-07-30

Embryonic stem cells can develop into a multitude of cells types. Researchers would like to understand how to channel that development into the specific types of mature cells that make up the organs and other structures of living organisms.

One key seems to be long chains of sugars that dangle from proteins on surfaces of cells.

Kamil Godula's group at the University of California, San Diego, has created synthetic molecules that can stand in for the natural sugars, but can be more easily manipulated to direct the process, they report in the Journal of the American ...

Peru's carbon quantified: Economic and conservation boon

2014-07-30

Washington, DC—Today scientists unveiled the first high-resolution map of the carbon stocks stored on land throughout the entire country of Perú. The new and improved methodology used to make the map marks a sea change for future market-based carbon economies. The new carbon map also reveals Perú's extremely high ecological diversity and it provides the critical input to studies of deforestation and forest degradation for conservation, land use, and enforcement purposes. The technique includes the determination of uncertainty of carbon stores throughout the country, which ...

New catalyst converts carbon dioxide to fuel

2014-07-30

Scientists from the University of Illinois at Chicago have synthesized a catalyst that improves their system for converting waste carbon dioxide into syngas, a precursor of gasoline and other energy-rich products, bringing the process closer to commercial viability.

Amin Salehi-Khojin, UIC professor of mechanical and industrial engineering, and his coworkers developed a unique two-step catalytic process that uses molybdenum disulfide and an ionic liquid to "reduce," or transfer electrons, to carbon dioxide in a chemical reaction. The new catalyst improves efficiency and ...

Spin-based electronics: New material successfully tested

2014-07-30

Spintronics is an emerging field of electronics, where devices work by manipulating the spin of electrons rather than the current generated by their motion. This field can offer significant advantages to computer technology. Controlling electron spin can be achieved with materials called 'topological insulators', which conduct electrons only across their surface but not through their interior. One such material, samarium hexaboride (SmB6), has long been theorized to be an ideal and robust topological insulator, but this has never been shown practically. Publishing in Nature ...

Big data confirms climate extremes are here to stay

2014-07-30

In a paper published online today in the journal Scientific Reports, published by Nature, Northeastern researchers Evan Kodra and Auroop Ganguly found that while global temperature is indeed increasing, so too is the variability in temperature extremes. For instance, while each year's average hottest and coldest temperatures will likely rise, those averages will also tend to fall within a wider range of potential high and low temperate extremes than are currently being observed. This means that even as overall temperatures rise, we may still continue to experience extreme ...