(Press-News.org) This news release is available in German.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) can take up gases similar to a sponge that soaks up liquids. Hence, these highly porous materials are suited for storing hydrogen or greenhouse gases. However, loading of many MOFs is inhibited by barriers. Scien-tists of Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) now report in Nature Communications that the barriers are caused by cor-rosion of the MOF surface. This can be prevented by water-free synthesis and storing strategies.

MOFs are crystalline materials consisting of metallic nodes and organic connection elements. They have a very large surface area and are highly porous. Like a sponge, they can take up other mole-cules. MOFs, produced on a large technical scale, are highly suited for the storage of gases: When the gas enters the solid, it is partly liquefied. The density increases and much more molecules can be stored in the same volume. Among others, MOFs are suited for the storage of hydrogen in the tank of hydrogen-driven automobiles. They can also be used for storing greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane. Other applications are substance separation, catalysis, and sensor technology. For any application, an appropri-ate MOF can be produced. Mostly, MOFs have the form of a pow-der. In the past ten years, more than 20,000 different representatives of this class have been synthesized and characterized in detail.

"For nearly all applications, loading of these highly porous crystals with molecules is essential," Lars Heinke of the Institute of Function-al Interfaces (IFG) of KIT explains. "The efficiency of molecule transport into the porous particles is crucial to the performance of the MOFs." In many MOF materials, however, loading is inhibited largely by so-called surface barriers. The surface of the sponge is broken, the pores are clogged, and loading is delayed significantly. This limits the application opportunities.

To better understand and identify the reasons of these problems, the IFG researchers studied the formation of surface barriers. For this purpose, they conducted fundamental experiments on thin, structurally perfect MOF layers mounted on solid substrates. These SURMOFs (SURface-mounted Metal-Organic Frameworks) are characterized by a high order and ideal structure. The researchers succeeded in attributing the barriers to a corrosion of MOF layers on the surface. They demonstrated how corrosion of the surface layer proceeds and found that water plays a central role. "Many scientists thought that these surface barriers are intrinsic and, hence, cannot be prevented. This assumption has now been disproved. It is possible to produce MOFs for loading without "clogging"," says the Head of KIT's IFG, Professor Christof Wöll. The work reported in the journal "Nature Communications" refutes several previous hypotheses.

The findings might be helpful for many applications of MOFs. Due to the results of the KIT researchers, water-free synthesis strategies for MOFs will have to be developed in the future. Improved materials will ensure barrier-free transport of molecules from the gas phase and liquid phase into MOFs. This will enable to further increase the efficiency of these promising storage and functional materials.

INFORMATION:

L. Heinke, Z. Gu, and Ch. Wöll, The surface barrier phenomenon in the loading of metal-organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 5:4462 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5562 (2014).

The Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) is a public corpora-tion according to the legislation of the state of Baden-Württemberg. It fulfills the mission of a university and the mis-sion of a national research center of the Helmholtz Association. Research activities focus on energy, the natural and built envi-ronment as well as on society and technology and cover the whole range extending from fundamental aspects to application. With about 9400 employees, including more than 6000 staff members in the science and education sector, and 24500 students, KIT is one of the biggest research and education in-stitutions in Europe. Work of KIT is based on the knowledge triangle of research, teaching, and innovation.

This press release is available on the internet at http://www.kit.edu.

The photo of printing quality may be downloaded under http://www.kit.edu or requested by mail to presse@kit.edu or phone +49 721 608-4 7414. The photo may be used in the context given above exclusively.

Free pores for molecule transport

Researchers identify cause of surface barriers of metal-organic frameworks -- relevant to gas storage

2014-07-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists shine bright new light on how living things capture energy from the sun

2014-07-31

Since Alexandre Edmond Becquerel first discovered the photovoltaic effect in 1839, humankind has sought to further understand and harness the power of sunlight for its own purposes. In a new research report published in the August 2014 issue of the FASEB Journal, scientists may have uncovered a new method of exploiting the power of sunlight by focusing on a naturally occurring combination of lipids that have been strikingly conserved throughout evolution. This conservation—or persistence over time and across species—suggests that this specific natural combination of lipids ...

Misinformation diffusing online

2014-07-31

The spread of misinformation through online social networks is becoming an increasingly worrying problem. Researchers in India have now modeled how such fictions and diffuse through those networks. They described details of their research and the taxonomy that could help those who run, regulate and use online social networks better understand how to slow or even prevent the spread of misinformation to the wider public.

Krishna Kumar and G. Geethakumari of the Department of Computer Science and Information Systems, at BITS-Pilani, Hyderabad Campus, in Andhra Pradesh, India, ...

Lead in teeth can tell a body's tale, UF study finds

2014-07-31

GAINESVILLE, Fla. – Your teeth can tell stories about you, and not just that you always forget to floss.

A study led by University of Florida geology researcher George D. Kamenov showed that trace amounts of lead in modern and historical human teeth can give clues about where they came from. The paper will be published in the August issue of Science of The Total Environment.

The discovery could help police solve cold cases, Kamenov said. For instance, if an unidentified decomposed body is found, testing the lead in the teeth could immediately help focus the investigation ...

Scientists discover biochemical mechanisms contributing to fibromuscular dysplasia

2014-07-31

An important step has been made to help better identify and treat those with fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD). FMD causes both an abnormal narrowing and enlarging of medium sized arteries in the body, which can restrict blood flow to the kidneys and other organs causing damage. In a new report appearing in August 2014 issue of The FASEB Journal, scientists provide evidence that that FMD may not be limited to the arteries as currently believed. In addition, they show a connection to abnormalities of bones and joints, as well as evidence that inflammation may be driving the ...

New paper describes how DNA avoids damage from UV light

2014-07-31

BOZEMAN, Mont. – In the same week that the U.S. surgeon general issued a 101-page report about the dangers of skin cancer, researchers at Montana State University published a paper breaking new ground on how DNA – the genetic code in every cell – responds when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light.

The findings advance fundamental understanding of DNA damage by the UV rays found in sunlight. This damage can lead to skin cancer, aging and some degenerative eye diseases.

"Our paper advances foundational knowledge about how DNA responds to UV radiation. In our experiments, ...

Magnetic resonance imaging in patients with transient ischemic attack

2014-07-31

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) is a temporary event, which portends a higher risk of a disabling stroke following the TIA. However, the evaluation and management of TIA vary worldwide and is debated and controversial. Dr. Mohamed Al-Khaled from University of Lübeck in Germany considered With the development of brain imaging, particularly diffusion weighted imaging-magnetic resonance imaging (DWI-MRI), the diagnosis of TIA changed from time-based definition to a tissue-based one. DWI-MRI became a mandatory tool in the TIA workup. The DWI-MRI provides not only the evidence ...

Ligaments disruption: A new perspective in the prognosis of SCI

2014-07-31

Worldwide prevalence of Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) is ranging from 233 to 755 per million inhabitants, whereas reported incidence lies between 10.4 and 83 per million inhabitants per year. Thus, the socioeconomic impact of SCI associated with cervical trauma is high enough to be encountered within one of the most important worries in vast majority of developed countries.

The ability to predict recovery following SCI is of paramount importance to the physician's role in providing the best care and guidance to patients and families during the illness. Diagnosis of cervical ...

Brother of Hibiscus is found alive and well on Maui

2014-07-31

Most people are familiar with Hibiscus flowers- they are an iconic symbol of tropical resorts worldwide where they are commonly planted in the landscape. Some, like Hawaii's State Flower- Hibiscus brackenridgei- are endangered species.

Only a relatively few botanists and Hawaiian conservation workers, however, are aware of an equally beautiful and intriguing related group of plants known as Hibiscadelphus- literally "brother of Hibiscus".

Brother of Hibiscus species are in fact highly endangered. Until recently only one of the seven previously known species remained ...

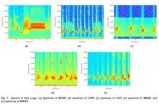

Singing the same tune: Scientists develop novel ways of separating birdsong sources

2014-07-31

Researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles and the Chinese Academy of Sciences have pioneered a new study that could greatly improve current methods of localising birdsong data. Their findings, which ascertain the validity of using statistical algorithms to detect multiple-source signals in real time and in three-dimensional space, are of especial significance to modern warfare.

Recently published in the journal Unmanned Systems, the study demonstrates the validity of using approximate maximum likelihood (AML) algorithms to determine the direction of arrival ...

Gulf oil spill researcher: Bacteria ate some toxins, but worst remain

2014-07-31

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — A Florida State University researcher found that bacteria in the Gulf of Mexico consumed many of the toxic components of the oil released during the Deepwater Horizon spill in the months after the spill, but not the most toxic contaminants.

In two new studies conducted in a deep sea plume, Assistant Professor Olivia Mason found a species of bacteria called Colwellia likely consumed gaseous hydrocarbons and perhaps benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene compounds that were released as part of the oil spill.

But, her research also showed that bacteria ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

App aids substance use recovery in vulnerable populations

College students nationwide received lifesaving education on sudden cardiac death

[Press-News.org] Free pores for molecule transportResearchers identify cause of surface barriers of metal-organic frameworks -- relevant to gas storage