(Press-News.org) In the first evidence that natural selection favors an individual's infection tolerance, researchers from Princeton University and the University of Edinburgh have found that an animal's ability to endure an internal parasite strongly influences its reproductive success. Reported in the journal PLoS Biology, the finding could provide the groundwork for boosting the resilience of humans and livestock to infection.

The researchers used 25 years of data on a population of wild sheep living on an island in northwest Scotland to assess the evolutionary importance of infection tolerance. They first examined the relationship between each sheep's body weight and its level of infection with nematodes, tiny parasitic worms that thrive in the gastrointestinal tract of sheep. The level of infection was determined by the number of nematode eggs per gram of the animal's feces.

While all of the animals lost weight as a result of nematode infection, the degree of weight loss varied widely: an adult female sheep with the maximum egg count of 2,000 eggs per gram of feces might lose as little as 2 percent or as much as 20 percent of her body weight. The researchers then tracked the number of offspring produced by each of nearly 2,500 sheep and found that sheep with the highest tolerance to nematode infection produced the most offspring, while sheep with lower parasite tolerance left fewer descendants.

To measure individual differences in parasite tolerance, the researchers used statistical methods that could be extended to studies of disease epidemiology in humans, said senior author Andrea Graham, an assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Princeton. Medical researchers have long understood that people with similar levels of parasite infection can experience very different symptoms. But biologists are just beginning to appreciate the evolutionary importance of this individual variation.

"For a long time, people assumed that if you knew an individual's parasite burden, you could perfectly predict its health and survival prospects," Graham said. "More recently, evolutionary biologists have come to realize that's not the case, and so have developed statistical tools to measure variation among hosts in the fitness consequences of infection."

Graham and her colleagues used the wealth of information collected over many years on the Soay sheep living on the island of Hirta, about 100 miles west of the Scottish mainland. These sheep provide a unique opportunity to study the effects of parasites, weather, vegetation changes and other factors on a population of wild animals. Brought to the island by people about 4,000 years ago, the sheep have run wild since the last permanent human inhabitants left Hirta in 1930. By keeping a detailed pedigree, the researchers of the St Kilda Soay Sheep Project can trace any individual's ancestry back to the beginning of the project in 1985, and, conversely, can count the number of descendants left by each individual.

Expending energy to fight infection

Nematodes puncture an animal's gut and can impede the absorption of nutrients. Therefore, tolerance to nematode infection could result from an ability to make up for the lost nutrition, or from the ability to repair damage the parasites cause to the gut, Graham said. "This island is way out in the North Atlantic, where the sun doesn't shine much," she said. "So tolerant individuals might be the ones who are better able to compete for food or better able to assimilate protein and other useful nutrients from the limited forage."

Tolerant animals might invest energy in gut repair, but would then be expected to incur costs. Graham and her colleagues identified a similar evolutionary tradeoff in a 2010 study that compared immune-response levels and reproductive success in female Soay sheep. They found that animals with strong antibody responses produced fewer offspring each year, but also lived longer. The team has not yet been able to detect costs of parasite tolerance in the sheep, but such costs could help explain variation in tolerance if the most tolerant animals were at a disadvantage under particular conditions.

While the PLoS Biology findings provide strong evidence that natural selection favors infection tolerance, they do raise questions, such as how the tolerance is generated, and why variation might persist from one generation to the next despite the reproductive advantage of tolerance, Graham said. The data in this study did not permit the researchers to detect a genetic component to tolerance. If genetics do play a role, she suspects multiple genes may interact with environmental factors to determine tolerance; ongoing research will help to tease apart these possibilities.

Understanding the genetic underpinnings of nematode tolerance could someday guide efforts to boost tolerance in livestock by identifying and selectively breeding those animals that exhibit a heightened parasite tolerance, said David Schneider, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford University.

"This study shows that parasite tolerance can have a profound effect on animal health and breeding success," said Schneider, who is familiar with the work but was not involved in it. "In the long term, this suggests that it could be profitable to invest in breeding tolerant livestock."

In humans and domesticated animals, intestinal parasites are becoming increasingly resistant to the drugs used to treat infections, Graham said. If the availability of nutrients, even just during the first few months of life, impacts lifelong parasite tolerance, simple nutritional supplements could be an effective way to promote tolerance in people. About 2 billion people are persistently infected with intestinal nematode parasites worldwide, mostly in developing nations. Children are especially vulnerable to the worms' effects, which include anemia, stunted growth and cognitive difficulties.

"Ideally, we would clear the worms from the bellies of the kids who have those heavy burdens," Graham said. "But if we could also understand how to ameliorate the health consequences and thus promote tolerance of nematodes, that could be a very powerful tool."

INFORMATION:The study, published July 29 in the journal PLoS Biology, was led by Adam Hayward of the Universities of Edinburgh and Sheffield. Other co-authors were Daniel Nussey, Camillo Berenos, Jill Pilkington, Kathryn Watt and Josephine Pemberton, all of the University of Edinburgh. Alastair Wilson of the University of Exeter also was a co-author.

The study was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council of the United Kingdom and the European Research Council. Graham's research is supported by the Research and Policy for Infectious Disease Dynamics program of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security's Science and Technology Directorate and the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health.

Wild sheep show benefits of putting up with parasites

2014-08-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA sees Genevieve cross international date line as a Super-Typhoon

2014-08-07

Tropical Storm Genevieve had ups and downs in the Eastern Pacific and Central Pacific over the last week but once the storm crossed the International Dateline in the Pacific, it rapidly intensified into a Super Typhoon. NASA-NOAA's Suomi NPP satellite captured of the storm.

When Suomi NPP flew over Genevieve on August 7 at 01:48 UTC the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) instrument aboard captured an infrared image of the storm. VIIRS collects visible and infrared imagery and global observations of land, atmosphere, cryosphere and oceans. VIIRS flies aboard ...

Dramatic growth of grafted stem cells in rat spinal cord injuries

2014-08-07

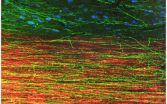

Building upon previous research, scientists at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Veteran's Affairs San Diego Healthcare System report that neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) and grafted into rats after a spinal cord injury produced cells with tens of thousands of axons extending virtually the entire length of the animals' central nervous system.

Writing in the August 7 early online edition of Neuron, lead scientist Paul Lu, PhD, of the UC San Diego Department of Neurosciences and colleagues said the human iPSC-derived ...

Human skin cells reprogrammed as neurons regrow in rats with spinal cord injuries

2014-08-07

While neurons normally fail to regenerate after spinal cord injuries, neurons formed from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that were grafted into rats with such injuries displayed remarkable growth throughout the length of the animals' central nervous system. What's more, the iPSCs were derived from skin cells taken from an 86-year-old man. The results, described in the Cell Press journal Neuron, could open up new possibilities in stimulating neuron growth in humans with spinal cord injuries

"These findings indicate that intrinsic neuronal mechanisms readily ...

Cancer study reveals powerful new system for classifying tumors

2014-08-07

Cancers are classified primarily on the basis of where in the body the disease originates, as in lung cancer or breast cancer. According to a new study, however, one in ten cancer patients would be classified differently using a new classification system based on molecular subtypes instead of the current tissue-of-origin system. This reclassification could lead to different therapeutic options for those patients, scientists reported in a paper published August 7 in Cell.

"It's only ten percent that were classified differently, but it matters a lot if you're one of those ...

Largest cancer genomic study proposes 'disruptive' new system to reclassify tumors

2014-08-07

Novato, California: Researchers with The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have analyzed more than 3500 tumors on multiple genomic technology platforms, revealing a new approach to classifying cancers. This largest-of-its-kind study, published online August 7th in Cell featured major contributions by Buck faculty Christopher Benz, MD and Senior Staff Scientist Christina Yau, PhD.

TCGA scientists analyzed the DNA, RNA and protein from 12 different tumor types using six different TCGA "platform technologies" to see how the different tumor types compare to each other. The study ...

University of Minnesota research finds key piece to cancer cell survival puzzle

2014-08-07

An international team led by Eric A. Hendrickson of the University of Minnesota and Duncan Baird of Cardiff University has solved a key mystery in cancer research: What allows some malignant cells to circumvent the normal process of cell death that occurs when chromosomes get too old to maintain themselves properly?

Researchers have long known that chromosomal defects that occur as cells repeatedly divide over time are linked to the onset of cancer. Now, Hendrickson, Baird and colleagues have identified a specific gene that human cells require in order to survive these ...

Notch developmental pathway regulates fear memory formation

2014-08-07

Nature is thrifty. The same signals that embryonic cells use to decide whether to become nerves, skin or bone come into play again when adult animals are learning whether to become afraid.

Researchers at Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Emory University, have learned that the molecule Notch, critical in many processes during embryonic development, is also involved in fear memory formation. Understanding fear memory formation is critical to developing more effective treatments and preventions for anxiety disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The ...

Scientists uncover stem cell behavior of human bowel for the first time

2014-08-07

For the first time, scientists have uncovered new information on how stem cells in the human bowel behave, revealing vital clues about the earliest stages in bowel cancer development and how we may begin to prevent it.

The study, led by Queen May University of London (QMUL) and published today in the journal Cell Reports, discovered how many stem cells exist within the human bowel and how they behave and evolve over time. It was revealed that within a healthy bowel, stem cells are in constant competition with each other for survival and only a certain number of stem ...

Cancer categories recast in largest-ever genomic study

2014-08-07

New research partly led by UC San Francisco-affiliated scientists suggests that one in 10 cancer patients would be more accurately diagnosed if their tumors were defined by cellular and molecular criteria rather than by the tissues in which they originated, and that this information, in turn, could lead to more appropriate treatments.

In the largest study of its kind to date, scientists analyzed molecular and genetic characteristics of more than 3,500 tumor samples of 12 different cancer types using multiple genomic technology platforms.

Cancers traditionally have ...

Scientists uncover key piece to cancer cell survival puzzle

2014-08-07

A chance meeting between two leading UK and US scientists could have finally helped solve a key mystery in cancer research.

Scientists have long known that chromosomal defects occur as cells repeatedly divide. Over time, these defects are linked to the onset of cancer.

Now, Professor Duncan Baird and his team from Cardiff University working in collaboration with Eric A. Hendrickson from the University of Minnesota, have identified a specific gene that human cells require in order to survive these types of defects.

"We have found a gene that appears to be crucial ...