(Press-News.org) A lung-damaging bacterium turns the body's antibody response in its favor, according to a study published in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Pathogenic bacteria are normally destroyed by antibodies, immune proteins that coat the outer surface of the bug, laying a foundation for the deposition of pore-forming "complement" proteins that poke lethal holes in the bacterial membrane. But despite having plenty of antibodies and complement proteins in their bloodstream, some people can't fight off infections with the respiratory bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. And chronic infection can lead to a condition called bronchiectasis, characterized by persistent cough, shortness of breath, and chest pain.

A group of researchers at the University of Birmingham, England, now find that the antibody response to Pseudomonas can get in its own way. In a subset of infected bronchiectasis patients with particularly poor lung function, they noticed an abundance of one specific type of antibody, called IgG2, which stripped the blood of its normal bug-killing capacity. The IgG2 proteins bound to extra-long sugars on the bacterial surface, a feature unique to the bugs infecting these patients. When these sugar-specific antibodies were removed, the blood's antibacterial prowess was restored.

Exactly how these IgG2 molecules protect the bug is unclear, but they may lure complement proteins away from more vulnerable parts of the bacterial surface. The discovery of antibodies that protect the bug instead of the person may help to explain why two vaccines based on these extra-long sugars resulted in worse disease in immunized individuals.

INFORMATION:

Wells, T.J., et al. 2014. J. Exp. Med. doi:10.1084/jem.20132444

About The Journal of Experimental Medicine

The Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM) is published by The Rockefeller University Press. All editorial decisions on manuscripts submitted are made by active scientists in conjunction with our in-house scientific editors. JEM content is posted to PubMed Central, where it is available to the public for free six months after publication. Authors retain copyright of their published works and third parties may reuse the content for non-commercial purposes under a creative commons license. For more information, please visit http://www.jem.org .

Sugary bugs subvert antibodies

2014-08-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Tackling liver injury

2014-08-11

A new drug spurs liver regeneration after surgery, according to a paper published in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Liver cancer often results in a loss of blood flow and thus oxygen and nutrients to the liver tissue, resulting in deteriorating liver function. Although the diseased part of the liver can often be surgically removed, the sudden restoration of blood flow to the remaining liver tissue can trigger inflammation—a process known as ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI). IRI results in part from the deposition of immune proteins called complement on the surface ...

'Seeing' through virtual touch is believing

2014-08-11

Visual impairment comes in many forms, and it's on the rise in America.

A University of Cincinnati experiment aimed at this diverse and growing population could spark development of advanced tools to help all the aging baby boomers, injured veterans, diabetics and white-cane-wielding pedestrians navigate the blurred edges of everyday life.

These tools could be based on a device called the Enactive Torch, which looks like a combination between a TV remote and Captain Kirk's weapon of choice. But it can do much greater things than change channels or stun aliens.

Luis ...

Aberrant mTOR signaling impairs whole body physiology

2014-08-11

The protein mTOR is a central controller of growth and metabolism. Deregulation of mTOR signaling increases the risk of developing metabolic diseases such as diabetes, obesity and cancer. In the current issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers from the Biozentrum of the University of Basel describe how aberrant mTOR signaling in the liver not only affects hepatic metabolism but also whole body physiology.

The protein mTOR regulates cell growth and metabolism and thus plays a key role in the development of human disorders. In the ...

Not only in DNA's hands

2014-08-11

Blood stem cells have the potential to turn into any type of blood cell, whether it be the oxygen-carrying red blood cells, or the many types of white blood cells of the immune system that help fight infection. How exactly is the fate of these stem cells regulated? Preliminary findings from research conducted by scientists from the Weizmann Institute and the Hebrew University are starting to reshape the conventional understanding of the way blood stem cell fate decisions are controlled thanks to a new technique for epigenetic analysis they have developed. Understanding ...

All-you-can-eat at the end of the universe

2014-08-11

At the ends of the Universe there are black holes with masses equaling billions of our sun. These giant bodies – quasars – feed on interstellar gas, swallowing large quantities of it non-stop. Thus they reveal their existence: The light that is emitted by the gas as it is sucked in and crushed by the black hole's gravity travels for eons across the Universe until it reaches our telescopes. Looking at the edges of the Universe is therefore looking into the past. These far-off, ancient quasars appear to us in their "baby photos" taken less than a billion years after the Big ...

Nanocubes get in a twist

2014-08-11

Nanocubes are anything but child's play. Weizmann Institute scientists have used them to create surprisingly yarn-like strands: They showed that given the right conditions, cube-shaped nanoparticles are able to align into winding helical structures. Their results, which reveal how nanomaterials can self-assemble into unexpectedly beautiful and complex structures, were recently published in Science.

Dr. Rafal Klajn and postdoctoral fellow Dr. Gurvinder Singh of the Institute's Organic Chemistry Department used nanocubes of an iron oxide material called magnetite. As ...

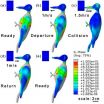

How the woodpecker avoids brain injury despite high-speed impacts via optimal anti-shock body structure

2014-08-11

Designing structures and devices that protect the body from shock and vibrations during high-velocity impacts is a universal challenge.

Scientists and engineers focusing on this challenge might make advances by studying the unique morphology of the woodpecker, whose body functions as an excellent anti-shock structure.

The woodpecker's brain can withstand repeated collisions and deceleration of 1200 g during rapid pecking. This anti-shock feature relates to the woodpecker's unique morphology and ability to absorb impact energy. Using computed tomography and the construction ...

Megascale icebergs run aground

2014-08-11

Scientists from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) have found between Greenland and Spitsbergen the scours left behind on the sea bed by gigantic icebergs. The five lineaments, at a depth of 1,200 metres, are the lowest-lying iceberg scours yet to be found on the Arctic sea floor. This finding provides new understanding of the dynamics of the Ice Age and the extent of the Arctic ice sheet thousands of years ago. In addition, the researchers could draw conclusions about the export of fresh water from the Arctic into the ...

Western Wall weathering: Extreme erosion explained

2014-08-11

Visitors to the Western Wall in Jerusalem can see that some of its stones are extremely eroded. This is good news for people placing prayer notes in the wall's cracks and crevices, but presents a problem for engineers concerned about the structure's stability.

The Western Wall is a remnant of the ancient wall that surrounded the courtyard of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. It is located in Jerusalem's Old City at the foot of the Temple Mount.

To calculate the erosion in the different kinds of limestone that make up the Western Wall, researchers from the Hebrew University ...

Celebrity promotion of charities 'is largely ineffective,' says research

2014-08-11

Celebrity promotion of charities is ineffective at raising awareness, but can make the stars more popular with the public, new research says.

According to journal articles by three UK academics, "the ability of celebrity and advocacy to reach people is limited" and celebrities are "generally ineffective" at encouraging people to care about "distant suffering".

The research, by Professor Dan Brockington, of The University of Manchester, Professor Spensor Henson, University of Sussex, and Dr Martin Scott, University of East Anglia, is published at time when many celebrities ...