(Press-News.org) How genes affect intelligence is complicated. Multiple genes, many yet unknown, are thought to interact among themselves and with environmental factors to influence the diverse abilities involved in intelligence.

A large new genetic study in thousands of children and adolescents offers early glimpses of the overall patterns and connections among cognitive abilities such as language reasoning, reading skill and types of memory. The findings may lead to new tools in understanding human cognitive development and neuropsychiatric disorders.

"This research is one of the first to use a molecular genetic approach to evaluate complex cognitive traits in a pediatric sample," said one of the study's two co-senior leaders, Hakon Hakonarson, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Center for Applied Genomics at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. "Uncovering the genetic architecture of these diverse cognitive abilities may offer new insights into cognitive development and may ultimately allow investigators to identify useful biomarkers for diagnosing and predicting risks of neuropsychiatric conditions."

The study appeared online July 15 in Molecular Psychiatry. Hakonarson's co-senior author is psychiatrist Raquel Gur, M.D., Ph.D., director of Neuropsychiatry in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. "We are beginning to reap the benefits of the major investment we made in recruiting this highly informative youth cohort," said Gur. She added, "They were genotyped and underwent 'deep phenotyping' that included medical, neuropsychiatric, and neurocognitive evaluations and multi-modal neuroimaging in a large subsample. This cohort will continue to yield novel information on how genes and environment interact to produce a mature, healthy brain and will elucidate how aberrations in brain function lead to cognitive deficits and psychopathology."

The study team represents a collaboration among the CHOP and Penn investigators with colleagues at the Broad Institute, Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) who developed a powerful gene software tool called genomewide complex trait analysis (GCTA). The study's first author is Elise B. Robinson, Ph.D., of the MGH Analytic and Translational Genetics Unit, led by Mark Daly, Ph.D.

The researchers used GCTA to analyze a subset of 3,689 individuals aged 8 to 21, all of European ancestry, drawn from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort, a general-population sample of close to 10,000 individuals who received care within CHOP's pediatric network for a broad range of health needs. The researchers performed genotypes of all participants, administered a battery of neurocognitive tests and assessed participants in structured psychiatric interviews.

The GCTA analyzes common SNPs (single-nucleotide polymorphisms, changes of a single base in DNA) to estimate how much these common gene variants contribute to differences in cognitive abilities within the total sample. The study team grouped cognitive traits within five broad domains: executive function, memory, complex cognition, social cognition and reading ability.

"When we computed the contribution of common variants to these cognitive abilities, we found that some of the contributions were substantial," said Hakonarson. For instance, common SNPs accounted for roughly 40 percent of the population differences in nonverbal reasoning, and 30 percent of the differences in language reasoning, with the balance of the differences attributable to rare variants and environmental factors. On the other hand, common gene variants together contributed to only 3 percent of the differences in spatial memory—the ability to navigate in a geographical location.

There also were significant overlaps between trait domains. Reading ability, which was 43 percent attributable to common variants, was often inherited together with language reasoning abilities. "Intuitively, it makes sense that skills in reading and language reasoning are related," said Hakonarson, who added that those traits might be investigated together in future genetic and neurobiological studies.

The current study drew on the largest data set ever used in a single sample across multiple cognitive domains. Previous estimates of the heritability of cognitive traits relied on much smaller twin and family studies. However, the authors note that their current research represents a first step in discerning the overall genetic architecture of cognitive abilities. Future studies, said Hakonarson, will analyze age-dependent differences, to investigate how genetic influences vary as children mature. Other, larger studies should focus on non-European populations.

Ultimately, added Hakonarson, if the current findings are replicated and extended, researchers may be able to generate a genetic profile reflecting a normal distribution of cognitive abilities. He said that detecting gene patterns that act as biomarkers for cognitive impairments may allow future researchers to better predict in early childhood the potential risk of developing later neuropsychiatric conditions, and may offer opportunities for early clinical interventions.

INFORMATION:

E.B. Robinson et al, "The genetic architecture of pediatric cognitive abilities in the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort," Molecular Psychiatry, published online July 15, 2014. http://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2014.65

In addition to his position at CHOP, Hakonarson also is on the faculty of the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Study funding came from the National Institutes of Health (grants MH089983, MH089924, and MH099286-01A1).

About The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia: The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia was founded in 1855 as the nation's first pediatric hospital. Through its long-standing commitment to providing exceptional patient care, training new generations of pediatric healthcare professionals and pioneering major research initiatives, Children's Hospital has fostered many discoveries that have benefited children worldwide. Its pediatric research program receives the highest amount of National Institutes of Health funding among all U.S. children's hospitals. In addition, its unique family-centered care and public service programs have brought the 535-bed hospital recognition as a leading advocate for children and adolescents. For more information, visit http://www.chop.edu.

Clues emerge to genetic architecture of cognitive abilities in children

CHOP expert, collaborators among first to use molecular genetic approach to evaluate complex traits in children's intelligence

2014-08-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

More intensive interventions needed to combat severe obesity in teens

2014-08-11

New Rochelle, NY, August 11, 2014 -- Nearly 6% of all children and teens in the U.S. are severely obese, and the prevalence of severe obesity is increasing faster than that of moderate obesity or overweight. This is an alarming trend as about 90% of these youths will grow up to be obese adults. The serious health problems associated with severe obesity and the poor long-term prognosis and quality of life projected for these children and teens demand more serious consideration of safe and effective treatment options that go beyond diet and lifestyle modifications, as proposed ...

Pairing old technologies with new for next-generation electronic devices

2014-08-11

UCL scientists have discovered a new method to efficiently generate and control currents based on the magnetic nature of electrons in semi-conducting materials, offering a radical way to develop a new generation of electronic devices.

One promising approach to developing new technologies is to exploit the electron's tiny magnetic moment, or 'spin'. Electrons have two properties – charge and spin – and although current technologies use charge, it is thought that spin-based technologies have the potential to outperform the 'charge'-based technology of semiconductors for ...

Sugary bugs subvert antibodies

2014-08-11

A lung-damaging bacterium turns the body's antibody response in its favor, according to a study published in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Pathogenic bacteria are normally destroyed by antibodies, immune proteins that coat the outer surface of the bug, laying a foundation for the deposition of pore-forming "complement" proteins that poke lethal holes in the bacterial membrane. But despite having plenty of antibodies and complement proteins in their bloodstream, some people can't fight off infections with the respiratory bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. And chronic ...

Tackling liver injury

2014-08-11

A new drug spurs liver regeneration after surgery, according to a paper published in The Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Liver cancer often results in a loss of blood flow and thus oxygen and nutrients to the liver tissue, resulting in deteriorating liver function. Although the diseased part of the liver can often be surgically removed, the sudden restoration of blood flow to the remaining liver tissue can trigger inflammation—a process known as ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI). IRI results in part from the deposition of immune proteins called complement on the surface ...

'Seeing' through virtual touch is believing

2014-08-11

Visual impairment comes in many forms, and it's on the rise in America.

A University of Cincinnati experiment aimed at this diverse and growing population could spark development of advanced tools to help all the aging baby boomers, injured veterans, diabetics and white-cane-wielding pedestrians navigate the blurred edges of everyday life.

These tools could be based on a device called the Enactive Torch, which looks like a combination between a TV remote and Captain Kirk's weapon of choice. But it can do much greater things than change channels or stun aliens.

Luis ...

Aberrant mTOR signaling impairs whole body physiology

2014-08-11

The protein mTOR is a central controller of growth and metabolism. Deregulation of mTOR signaling increases the risk of developing metabolic diseases such as diabetes, obesity and cancer. In the current issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers from the Biozentrum of the University of Basel describe how aberrant mTOR signaling in the liver not only affects hepatic metabolism but also whole body physiology.

The protein mTOR regulates cell growth and metabolism and thus plays a key role in the development of human disorders. In the ...

Not only in DNA's hands

2014-08-11

Blood stem cells have the potential to turn into any type of blood cell, whether it be the oxygen-carrying red blood cells, or the many types of white blood cells of the immune system that help fight infection. How exactly is the fate of these stem cells regulated? Preliminary findings from research conducted by scientists from the Weizmann Institute and the Hebrew University are starting to reshape the conventional understanding of the way blood stem cell fate decisions are controlled thanks to a new technique for epigenetic analysis they have developed. Understanding ...

All-you-can-eat at the end of the universe

2014-08-11

At the ends of the Universe there are black holes with masses equaling billions of our sun. These giant bodies – quasars – feed on interstellar gas, swallowing large quantities of it non-stop. Thus they reveal their existence: The light that is emitted by the gas as it is sucked in and crushed by the black hole's gravity travels for eons across the Universe until it reaches our telescopes. Looking at the edges of the Universe is therefore looking into the past. These far-off, ancient quasars appear to us in their "baby photos" taken less than a billion years after the Big ...

Nanocubes get in a twist

2014-08-11

Nanocubes are anything but child's play. Weizmann Institute scientists have used them to create surprisingly yarn-like strands: They showed that given the right conditions, cube-shaped nanoparticles are able to align into winding helical structures. Their results, which reveal how nanomaterials can self-assemble into unexpectedly beautiful and complex structures, were recently published in Science.

Dr. Rafal Klajn and postdoctoral fellow Dr. Gurvinder Singh of the Institute's Organic Chemistry Department used nanocubes of an iron oxide material called magnetite. As ...

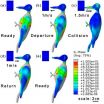

How the woodpecker avoids brain injury despite high-speed impacts via optimal anti-shock body structure

2014-08-11

Designing structures and devices that protect the body from shock and vibrations during high-velocity impacts is a universal challenge.

Scientists and engineers focusing on this challenge might make advances by studying the unique morphology of the woodpecker, whose body functions as an excellent anti-shock structure.

The woodpecker's brain can withstand repeated collisions and deceleration of 1200 g during rapid pecking. This anti-shock feature relates to the woodpecker's unique morphology and ability to absorb impact energy. Using computed tomography and the construction ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Does a past abortion or miscarriage affect a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer?

Could a treatment redirect the body’s anti-viral immune response to target cancer cells?

How does universal, free prescription drug coverage affect older adults’ finances and behaviors?

Do certain factors affect life expectancy in people with spina bifida?

New study: Routine aspirin therapy prevents severe preeclampsia in at-risk populations

Afraid of chemistry at school? It’s not all the subject’s fault

How tech-dependency and pandemic isolation have created ‘anxious generation’

Nearly three quarters of US baby foods are ultra-processed, new study finds

Nonablative radiofrequency may improve sexual function in postmenopausal women

Pulsed dynamic water electrolysis: Mass transfer enhancement, microenvironment regulation, and hydrogen production optimization

Coordination thermodynamic control of magnetic domain configuration evolution toward low‑frequency electromagnetic attenuation

High‑density 1D ionic wire arrays for osmotic energy conversion

DAYU3D: A modern code for HTGR thermal-hydraulic design and accident analysis

Accelerating development of new energy system with “substance-energy network” as foundation

Recombinant lipidated receptor-binding domain for mucosal vaccine

Rising CO₂ and warming jointly limit phosphorus availability in rice soils

Shandong Agricultural University researchers redefine green revolution genes to boost wheat yield potential

Phylogenomics Insights: Worldwide phylogeny and integrative taxonomy of Clematis

Noise pollution is affecting birds' reproduction, stress levels and more. The good news is we can fix it.

Researchers identify cleaner ways to burn biomass using new environmental impact metric

Avian malaria widespread across Hawaiʻi bird communities, new UH study finds

New study improves accuracy in tracking ammonia pollution sources

Scientists turn agricultural waste into powerful material that removes excess nutrients from water

Tracking whether California’s criminal courts deliver racial justice

Aerobic exercise may be most effective for relieving depression/anxiety symptoms

School restrictive smartphone policies may save a small amount of money by reducing staff costs

UCLA report reveals a significant global palliative care gap among children

The psychology of self-driving cars: Why the technology doesn’t suit human brains

Scientists discover new DNA-binding proteins from extreme environments that could improve disease diagnosis

Rapid response launched to tackle new yellow rust strains threatening UK wheat

[Press-News.org] Clues emerge to genetic architecture of cognitive abilities in childrenCHOP expert, collaborators among first to use molecular genetic approach to evaluate complex traits in children's intelligence