(Press-News.org) Scientists believe babies are born with digestive systems containing few or no bacteria. Their guts then quickly become colonized by microbes — good and bad — as they nurse or take bottles, receive medication and even as they are passed from one adoring relative to another.

However, in infants born prematurely, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found that the population of bacteria in babies' gastrointestinal tracts may depend more on their biological makeup and gestational age at birth than on environmental factors. The scientists discovered that bacterial communities assemble in an orderly, choreographed progression, with the pace of that assembly slowest in infants born most prematurely.

"Your earliest gut microbes probably have lifelong consequences, but we know very little about how these microbial communities assemble," said senior author Phillip I. Tarr, MD, the Melvin E. Carnahan Professor of Pediatrics. "Do these populations form as a result of random encounters, with an infant's gut supporting the growth of bacteria that enter this organ by chance? Or does the host have a role in selecting the microbes? Our research indicates that the gut is destined to define the bacteria that inhabit it. At 33-36 weeks after conception, preterm infants have very similar microbial populations in their guts."

The research appears Aug. 11 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) online early edition.

Bacterial colonization has lasting effects — influencing health and development, immune function, resistance to infection, and predisposition to inflammatory and metabolic disorders — yet, until now, little has been known about how the microbes get there.

Collaborators at The Genome Institute at Washington University School of Medicine used DNA sequencing to tally the bacterial populations in 922 stool samples from 58 premature infants. The babies, patients in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at St. Louis Children's Hospital, ranged from 23-33 weeks in gestational age and weighed 1,500 grams (3 pounds, 5 ounces) or less.

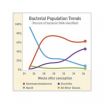

The investigators found that differing ratios of three major classes of bacteria colonized the preemies' guts in sequence. Earliest in life, a group of bacteria called Bacilli dominated. Then, a class known as Gammaproteobacteria became abundant. Third, the class identified as Clostridia flourished. Environmental factors — including whether the babies' deliveries were vaginal or cesarean, whether they had been given antibiotics, their ages when stools were sampled, and their diets — influenced the pace, but not the order, of the progression.

The researchers noted abrupt changes in each gut's bacterial composition along the way to 36 weeks in gestational age but found that somehow the gut ecosystems adjusted and returned to what seemed to be a preordained progression of bacterial colonization.

"Sometimes the abrupt changes were in the same direction as the overall progression, and at other times they weren't," said Tarr, who is also director of the Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. "That was unpredictable. But eventually the population proportions would correct, and those three classes of bacteria would remain the major components."

Armed with the knowledge of what occurs in the digestive systems of preemies in a controlled environment, the researchers' next aim to discern what happens in the systems of preemies who don't fare as well, particularly those suffering from necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC).

NEC is a devastating disorder in premature infants that causes tissue death in the lining of the intestinal wall. The syndrome occurs in up to 10 percent of premature infants and is fatal 25 to 35 percent of the time. Scientists believe gut microbes play a part in the disease.

"Research has not made an impact in either prevention or treatment of NEC," said co-first author Barbara Warner, MD, a professor of pediatrics who treats patients at St. Louis Children's Hospital. "The Holy Grail is prevention, and if so much of what happens in the gut depends on the host, this research may help us identify just what increases an infant's risk for developing NEC and help us target therapies."

Warner said she and her colleagues don't yet know the significance of the three bacterial classes that dominated the preemies' gut microbiota. But of the three, she said, Gammaproteobacteria are most intriguing because they are linked to inflammation and because there were so many of these microbes in the infants' guts.

In a healthy, older child's gut, Gammaproteobacteria typically are less than 1 percent of the bacteria. In this study, however, well over 50 percent of the bacteria in many of the premature infants' guts were Gammaproteobacteria. And in some infants, this group of microbes accounted for more than 80 percent of the bacteria.

What that means for preterm infants and how it might affect them in the long term are among questions raised by the new research, Warner and Tarr said.

"This is the largest and most intense sampling of newborn infant guts ever performed using modern sequencing technology, and we believe that the data from this study will be immensely helpful in understanding the human gut," Tarr said. "It is our first glimpse of how these earliest in life bacterial colonizations — events that may have lifelong consequences — occur."

INFORMATION: END

Preemies' gut bacteria may depend more on gestational age than environment

2014-08-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Bioengineers create functional 3-D brain-like tissue

2014-08-11

Bioengineers have created three-dimensional brain-like tissue that functions like and has structural features similar to tissue in the rat brain and that can be kept alive in the lab for more than two months.

As a first demonstration of its potential, researchers used the brain-like tissue to study chemical and electrical changes that occur immediately following traumatic brain injury and, in a separate experiment, changes that occur in response to a drug. The tissue could provide a superior model for studying normal brain function as well as injury and disease, and ...

Scientists demonstrate long-sought drug candidate can halt tumor growth

2014-08-11

LA JOLLA, CA – August 11, 2014 – It's a trick any cat burglar knows: to open a locked door, slide a credit card past the latch.

Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) tried a similar strategy when they attempted to disrupt the function of MYC, a cancer regulator thought to be "undruggable." The researchers found that a credit card-like molecule they developed somehow moves in and disrupts the critical interactions between MYC and its binding partner.

The research, published the week of August 11 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, ...

Elusive viral 'machine' architecture finally rendered

2014-08-11

VIDEO:

The new rendering of the protein-DNA complex, or machine, that the Lambda virus uses to insert its DNA into that of its E. coli host.

Click here for more information.

For half a century biologists have studied the way that the lambda virus parks DNA in the chromosome of a host E. coli bacterium and later extracts it as a model reaction of genetic recombination. But for all that time, they could never produce an overall depiction of the protein-DNA machines that carry out ...

Native bacteria block Wolbachia from being passed to mosquito progeny

2014-08-11

Native bacteria living inside mosquitoes prevent the insects from passing Wolbachia bacteria -- which can make the mosquitoes resistant to the malaria parasite -- to their offspring, according to a team of researchers.

The team found that Asaia, a type of bacteria that occurs naturally in Anopheles mosquitoes, blocks invasion of Wolbachia into the mosquitoes' germlines -- the cells that are passed on through successive generations of an organism -- thus stopping the insects from transmitting Wolbachia to their offspring.

"Wolbachia infects up to 70 percent of all known ...

Novel drug action against solid tumors explained

2014-08-11

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) — Researchers at UC Davis, City of Hope, Taipai Medical University and National Health Research Institutes in Taiwan have discovered how a drug that deprives the cells of a key amino acid specifically kills cancer cells.

Their paper, published today in Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences, is the culmination of nearly a decade of research into the role of arginine – and its deprivation – in the generation of excessive autophagy, a process in which the cell dies by eating itself.

Study co-author Hsing-Jien Kung, a renowned cancer biologist and ...

Reconstructions show how some of the earliest animals lived -- and died

2014-08-11

VIDEO:

This is an animation of the growth and development of the extinct rangeomorph species Beothukis mistakenis, which lived during the Ediacaran Period from approximately 575 to 555 million years ago....

Click here for more information.

A bizarre group of uniquely shaped organisms known as rangeomorphs may have been some of the earliest animals to appear on Earth, uniquely suited to ocean conditions 575 million years ago. A new model devised by researchers at the University ...

A vaccine alternative protects mice against malaria

2014-08-11

A study led by Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health researchers found that injecting a vaccine-like compound into mice was effective in protecting them from malaria. The findings suggest a potential new path toward the elusive goal of malaria immunization.

Mice, injected with a virus genetically altered to help the rodents create an antibody designed to fight the malaria parasite, produced high levels of the anti-malaria antibody. The approach, known as Vector immunoprophylaxis, or VIP, has shown promise in HIV studies but has never been tested with malaria, ...

Search for biomarkers aimed at improving treatment of painful bladder condition

2014-08-11

Winston-Salem, N.C. – August 11, 2014 – Taking advantage of technology that can analyze tissue samples and measure the activity of thousands of genes at once, scientists at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center are on a mission to better understand and treat interstitial cystitis (IC), a painful and difficult-to-diagnose bladder condition.

"We are looking for molecular biomarkers for IC, which basically means we are comparing bladder biopsy tissue from patients with suspected interstitial cystitis to patients without the disease. The goal is to identify factors that will ...

Highly drug resistant, virulent strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa arises in Ohio

2014-08-11

A team of clinician researchers has discovered a highly virulent, multidrug resistant form of the pathogen, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, in patient samples in Ohio. Their investigation suggests that the particular genetic element involved, which is still rare in the United States, has been spreading heretofore unnoticed, and that surveillance is urgently needed. The research is published ahead of print in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The P. aeruginosa contained a gene for a drug resistant enzyme called a metallo beta-lactamase. Beta-lactamases enable broad-spectrum ...

Want to kill creativity of women in teams? Fire up the competition

2014-08-11

Recent research has suggested that women play better with others in small working groups, and that adding women to a group is a surefire way to boost team collaboration and creativity.

But a new study from Washington University in St. Louis finds that this is only true when women work on teams that aren't competing against each other. Force teams to go head to head and the benefits of a female approach evaporate.

"Intergroup competition is a double-edged sword that ultimately provides an advantage to groups and units composed predominantly or exclusively of men, while ...