(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Gene-based personalized medicine has many possibilities for diagnosis and targeted therapy, but one big bottleneck: the expensive and time-consuming DNA-sequencing process.

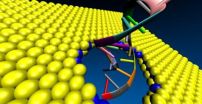

Now, researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have found that nanopores in the material molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) could sequence DNA more accurately, quickly and inexpensively than anything yet available.

"One of the big areas in science is to sequence the human genome for under $1,000, the 'genome-at-home,'" said Narayana Aluru, a professor of mechanical science and engineering at the U. of I. who led the study. "There is now a hunt to find the right material. We've used MoS2 for other problems, and we thought, why don't we try it and see how it does for DNA sequencing?"

As it turns out, MoS2 outperforms all other materials used for nanopore DNA sequencing – even graphene.

A nanopore is a very tiny hole drilled through a thin sheet of material. The pore is just big enough for a DNA molecule to thread through. An electric current drives the DNA through the nanopore, and the fluctuations in the current as the DNA passes through the pore tell the sequence of the DNA, since each of the four letters of the DNA alphabet – A, C, G and T – are slightly different in shape and size.

Most materials used for nanopore DNA sequencing have a sizable flaw: They are too thick. Even a thin sheet of most materials spans multiple links of the DNA chain, making it impossible to accurately determine the exact DNA sequence.

Graphene has become a popular alternative, since it is a sheet made of a single layer of carbon atoms – meaning only one base at a time goes through the nanopore. Unfortunately, graphene has its own set of problems, the biggest being that the DNA sticks to it. The DNA interacting with the graphene introduces a lot of noise that makes it hard to read the current, like a radio station marred by loud static.

MoS2 is also a single-layer sheet, thin enough that only one DNA letter at a time goes through the nanopore. In the study, the Illinois researchers found that DNA does not stick to MoS2, but threads through the pore cleanly and quickly. See an animation online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DVh-TT507rg.

"MoS2 is a competitor of graphene in terms of transistors, but we showed here a new functionality of this material by showing that it is capable of biosensing," said graduate student Amir Barati Farimani, the first author of the paper.

Most exciting for the researchers, the simulations yielded four distinct signals corresponding to the bases in a double-stranded DNA molecule. Other systems have yielded two at best – A/T and C/G – which then require extensive computational analysis to attempt to distinguish A from T and C from G.

The key to the success of the complex MoS2 simulation and analysis was the Blue Waters supercomputer, located at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the U. of I.

"These are very detailed calculations," said Aluru, who is also a part of the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology at the U. of I. "They really tell us the physics of the actual mechanisms, and why MoS2 is performing better than other materials. We have those insights now because of this work, which used Blue Waters extensively."

Now, the researchers are exploring whether they can achieve even greater performance by coupling MoS2 with another material to form a low-cost, fast and accurate DNA sequencing device.

"The ultimate goal of this research is to make some kind of home-based or personal DNA sequencing device," Barati Farimani said. "We are on the path to get there, by finding the technologies that can quickly, cheaply and accurately identify the human genome. Having a map of your DNA can help to prevent or detect diseases in the earliest stages of development. If everybody can cheaply sequence so they can know the map of their genetics, they can be much more alert to what goes on in their bodies."

INFORMATION:

The Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the National Science Foundation supported this work, published in the journal ACS Nano.

Editor's note: To reach Narayana Aluru, call 217-333-1180; email aluru@illinois.edu.

The paper, "DNA base detection using a single-layer MoS2," is available online at http://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/nn5029295.

New material could enhance fast and accurate DNA sequencing

2014-08-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Patent examiners more likely to approve marginal inventions when pressed for time

2014-08-13

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Haste makes waste, as the old saying goes. And according to research from a University of Illinois expert in patent law, the same adage could be applied to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, where high-ranking examiners have a tendency to rubber-stamp patents of questionable merit due to time constraints.

The less time patent examiners are given to review an application, the more likely they are to grant patent protection to inventions "on the margin," says a study co-authored by Melissa Wasserman, the Richard and Anne Stockton Faculty Scholar and ...

Bones from nearly 50 ancient flying reptiles discovered

2014-08-13

Scientists discovered the bones of nearly 50 winged reptiles from a new species, Caiuajara dobruskii, that lived during the Cretaceous in southern Brazil, according to a study published August 13, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Paulo Manzig from Universidade do Contestado, Brazil, and colleagues.

The authors discovered the bones in a pterosaur bone bed in rocks from the Cretaceous period. They belonged to individuals ranging from young to adult, with wing spans ranging from 0.65-2.35m, allowing scientists to analyze how the bones fit into their clade, but ...

Embalming study 'rewrites' chapter in Egyptian history

2014-08-13

The origins of mummification may have started in ancient Egypt 1,500 years earlier than previously thought, according to a study published August 13, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Stephen Buckley from University of York and colleagues from Macquarie University and University of Oxford.

Previous evidence suggests that between ~4500 B.C. and 3100 B.C., Egyptian mummification consisted of bodies desiccating naturally through the action of the hot, dry desert sand. The early use of resins in artificial mummification has, until now, been limited to isolated occurrences ...

Little penguins forage together

2014-08-13

Most little penguins may search for food in groups, and even synchronize their movements during foraging trips, according to a study published August 13, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Maud Berlincourt and John Arnould from Deakin University in Australia.

Little penguins are the smallest penguin species and they live exclusively in southern Australia, New Zealand, and the Chatham Islands, but spend most of their lives at sea in search of food. Not much is known about group foraging behavior in seabirds due to the difficulty in observing their remote feeding ...

Young blue sharks use central North Atlantic nursery

2014-08-13

Blue sharks may use the central North Atlantic as a nursery prior to males and females moving through the ocean basin in distinctly different patterns, according to a study published August 13, 2014 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Frederic Vandeperre from University of the Azores, Portugal, and colleagues.

Shark populations typically organize by location and separate by sex and size, but these patterns remain poorly understood, particularly for exploited oceanic species such as the blue shark. The authors of this study employed a long-term electronic tagging experiment ...

Bacterial biosurgery shows promise for reducing the size of inoperable tumors

2014-08-13

Kansas City, MO. — Deep within most tumors lie areas that remain untouched by chemotherapy and radiation. These troublesome spots lack the blood and oxygen needed for traditional therapies to work, but provide the perfect target for a new cancer treatment using bacteria that thrive in oxygen-poor conditions. Now, researchers have shown that injections of a weakened version of one such anaerobic bacteria -- the microbe Clostridium novyi -- can shrink tumors in rats, pet dogs, and a human patient.

The findings from BioMed Valley Discoveries and a nationwide team of collaborators ...

Embalming study 'rewrites' key chapter in Egyptian history

2014-08-13

Researchers from the Universities of York, Macquarie and Oxford have discovered new evidence to suggest that the origins of mummification started in ancient Egypt 1,500 years earlier than previously thought.

The scientific findings of an 11-year study by a researcher in the Department of Archaeology at York, and York's BioArCh facility, and an Egyptologist from the Department of Ancient History at Macquarie University, push back the origins of a central and vital facet of ancient Egyptian culture by over a millennium.

Traditional theories on ancient Egyptian mummification ...

Injected bacteria shrink tumors in rats, dogs and humans

2014-08-13

A modified version of the Clostridium novyi (C. noyvi-NT) bacterium can produce a strong and precisely targeted anti-tumor response in rats, dogs and now humans, according to a new report from Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center researchers.

In its natural form, C. novyi is found in the soil and, in certain cases, can cause tissue-damaging infection in cattle, sheep and humans. The microbe thrives only in oxygen-poor environments, which makes it a targeted means of destroying oxygen-starved cells in tumors that are difficult to treat with chemotherapy and radiation. The ...

Treatment with lymph node cells controls dangerous sepsis in animal models

2014-08-13

An immune-regulating cell present in lymph nodes may be able to halt severe cases of sepsis, an out-of-control inflammatory response that can lead to organ failure and death. In the August 13 issue of Science Translational Medicine, a multi-institutional research team reports that treatment with fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs) significantly improved survival in two mouse models of sepsis, even when delivered after the condition was well established. Even after treatment with antibiotics, sepsis remains a major cause of death.

"Our findings are important because, ...

Stimuli-responsive drug delivery system prevents transplant rejection

2014-08-13

Boston, MA – Following a tissue graft transplant—such as that of the face, hand, arm or leg—it is standard for doctors to immediately give transplant recipients immunosuppressant drugs to prevent their body's immune system from rejecting and attacking the new body part. However, there are toxicities associated with delivering these drugs systemically, as well as side effects since suppressing the immune system can make a patient vulnerable to infection.

A global collaboration including researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH); Institute for Stem Cell Biology ...