(Press-News.org) A modified version of the Clostridium novyi (C. noyvi-NT) bacterium can produce a strong and precisely targeted anti-tumor response in rats, dogs and now humans, according to a new report from Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center researchers.

In its natural form, C. novyi is found in the soil and, in certain cases, can cause tissue-damaging infection in cattle, sheep and humans. The microbe thrives only in oxygen-poor environments, which makes it a targeted means of destroying oxygen-starved cells in tumors that are difficult to treat with chemotherapy and radiation. The Johns Hopkins team removed one of the bacteria's toxin-producing genes to make it safer for therapeutic use.

For the study, the researchers tested direct-tumor injection of the C. noyvi-NT spores in 16 pet dogs that were being treated for naturally occurring tumors. Six of the dogs had an anti-tumor response 21 days after their first treatment. Three of the six showed complete eradication of their tumors, and the length of the longest diameter of the tumor shrunk by at least 30 percent in the three other dogs.

Most of the dogs experienced side effects typical of a bacterial infection, such as fever and tumor abscesses and inflammation, according to a report on the work published online Aug. 13 in Science Translational Medicine.

In a Phase I clinical trial of C. noyvi-NT spores conducted at MD Anderson Cancer Center, a patient with an advanced soft tissue tumor in the abdomen received the spore injection directly into a metastatic tumor in her arm. The treatment significantly reduced the tumor in and around the bone. "She had a very vigorous inflammatory response and abscess formation," according to Nicholas Roberts, Vet.M.B., Ph.D. "But at the moment, we haven't treated enough people to be sure if the spectrum of responses that we see in dogs will truly recapitulate what we see in people."

"One advantage of using bacteria to treat cancer is that you can modify these bacteria relatively easily, to equip them with other therapeutic agents, or make them less toxic as we have done here, " said Shibin Zhou, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of oncology at the Cancer Center. Zhou is also the director of experimental therapeutics at the Kimmel Cancer Center's Ludwig Center for Cancer Genetics and Therapeutics. He and colleagues at Johns Hopkins began exploring C. novyi's cancer-fighting potential more than a decade ago after studying hundred-year old accounts of an early immunotherapy called Coley toxins, which grew out of the observation that some cancer patients who contracted serious bacterial infections showed cancer remission.

The researchers focused on soft tissue tumors because "these tumors are often locally advanced, and they have spread into normal tissue," said Roberts, a Ludwig Center and Department of Pathology researcher. The bacteria cannot germinate in normal tissues and will only attack the oxygen-starved or hypoxic cells in the tumor and spare healthy tissue around the cancer.

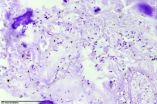

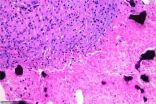

Verena Staedtke, M.D., Ph.D., a Johns Hopkins neuro-oncology fellow, first tested the spore injection in rats with implanted brain tumors called gliomas. Microscopic evaluation of the tumors showed that the treatment killed tumor cells but spared healthy cells just a few micrometers away. The treatment also prolonged the rats' survival, with treated rats surviving an average of 33 days after the tumor was implanted, compared with an average of 18 days in rats that did not receive the C. noyvi-NT spore injection.

The researchers then extended their tests of the injection to dogs. "One of the reasons that we treated dogs with C. noyvi-NT before people is because dogs can be a good guide to what may happen in people," Roberts said. The dog tumors share many genetic similarities with human tumors, he explained, and their tumors appeared spontaneously as they would in humans. Dogs are also treated with many of the same cancer drugs as humans and respond similarly.

The dogs showed a variety of anti-tumor responses and inflammatory side effects.

Zhou said that study of the C. noyvi-NT spore injection in humans is ongoing, but the final results of their treatment are not yet available. "We expect that some patients will have a stronger response than others, but that's true of other therapies as well. Now, we want to know how well the patients can tolerate this kind of therapy."

It may be possible to combine traditional treatments like chemotherapy with the C. noyvi-NT therapy, said Zhou, who added that the researchers have already studied these combinations in mice.

"Some of these traditional therapies are able to increase the hypoxic region in a tumor and would make the bacterial infection more potent and increase its anti-tumor efficiency," Staedtke suggested. "C. noyvi-NT is an agent that could be combined with a multitude of chemotherapy agents or radiation."

"Another good thing about using bacteria as a therapeutic agent is that once they're infecting the tumor, they can induce a strong immune response against tumor cells themselves," Zhou said.

Previous studies in mice, he noted, suggest that C. noyvi-NT may help create a lingering immune response that fights metastatic tumors long after the initial bacterial treatment, but this effect remains to be seen in the dog and human studies.

INFORMATION:

Other researchers on the study include Yuan Qiao, Luis A. Diaz Jr., Nickolas Papadopoulos, Kenneth W. Kinzler, Bert Vogelstein and Chetan Bettegowda of the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center's Ludwig Center; Linping Zhan, Amanda Collins, David Tung, Maria Miller, Jeffrey Roix, Halle H. Zhang, Mary Varterasian and Saurabh Saha of BioMed Valley Discoveries Inc.; Filip Janku, Thorunn Helgason, Ravi Murthy, Robert S. Benjamin, Ariel D. Szvalb, Justin E. Bird and Sinchita Roy-Chowdhuri of the MD Anderson Cancer Center; Ren-Yuan Bai and Gregory J. Riggins of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutes Department of Neurosurgery; Anthony W. Rusk and Kristen V. Khanna of Animal Clinical Investigation, LLC; Baktiar Karim and David L. Huso of the Johns Hopkins University Department of Molecular and Comparative Pathobiology; Jennifer McDaniel and Gerald Post of The Veterinary Cancer Center; Amanda Elpiner of VCA Great Lakes Veterinary Specialists; Alexandra Sahora of The Oncology Service, Friendship Hospital for Animals; Joshua Lachowicz of BluePearl Veterinary Partners; Brenda Phillips of Veterinary Specialty Hospital of San Diego; Avenelle Turner of Veterinary Cancer Group of Los Angeles at City of Angels Veterinary Specialty Center; and Mary K. Klein of Southern Arizona Veterinary Specialty and Emergency Center.

Funding for the study was provided by BioMed Valley Discoveries, Inc., the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research, the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund, the Commonwealth Fund, Swim Across America, the Burroughs Wellcome Career Award for Medical Scientists, Voices Against Brain Cancer, the Sol Goldman Pancreatic Cancer Research Center, the Johns Hopkins Clinician Scientist Award, and the National Institutes of Health's National Cancer Institute (CA129825 and CA062924) and National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (R25NS065729).

Under a licensing agreement between BioMed Valley Discoveries, Inc. and the Johns Hopkins University, Luis A. Diaz, Jr., Kenneth W. Kinzler, Bert Vogelstein, Chetan Bettegowda and Shibin Zhou are entitled to a share of royalties received by the University on sales of products described in this article. Their participation as co-authors did not include data analysis or interpretation of the clinical results described herein. Kinzler, Vogelstein, Bettegowda, and Zhou hold patents for work related to this study.

Images of C. noyvi-NT available upon request.

Related News Release:

Germ Chemo Combo Fights Cancer: http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/media/releases/germ__chemo_combo_fights_cancer

Media Contacts:

Vanessa Wasta, 410-614-2916, wasta@jhmi.edu

Valerie Mehl, 443-375-1991, mehlva@jhmi.edu

Injected bacteria shrink tumors in rats, dogs and humans

2014-08-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Treatment with lymph node cells controls dangerous sepsis in animal models

2014-08-13

An immune-regulating cell present in lymph nodes may be able to halt severe cases of sepsis, an out-of-control inflammatory response that can lead to organ failure and death. In the August 13 issue of Science Translational Medicine, a multi-institutional research team reports that treatment with fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs) significantly improved survival in two mouse models of sepsis, even when delivered after the condition was well established. Even after treatment with antibiotics, sepsis remains a major cause of death.

"Our findings are important because, ...

Stimuli-responsive drug delivery system prevents transplant rejection

2014-08-13

Boston, MA – Following a tissue graft transplant—such as that of the face, hand, arm or leg—it is standard for doctors to immediately give transplant recipients immunosuppressant drugs to prevent their body's immune system from rejecting and attacking the new body part. However, there are toxicities associated with delivering these drugs systemically, as well as side effects since suppressing the immune system can make a patient vulnerable to infection.

A global collaboration including researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH); Institute for Stem Cell Biology ...

Statistical model predicts performance of hybrid rice

2014-08-13

RIVERSIDE, Calif. — Genomic prediction, a new field of quantitative genetics, is a statistical approach to predicting the value of an economically important trait in a plant, such as yield or disease resistance. The method works if the trait is heritable, as many traits tend to be, and can be performed early in the life cycle of the plant, helping reduce costs.

Now a research team led by plant geneticists at the University of California, Riverside and Huazhong Agricultural University, China, has used the method to predict the performance of hybrid rice (for example, the ...

Story ideas from NCAR: Seasonal hurricane forecasts, El Niño, wind energy, and more

2014-08-13

BOULDER – Researchers at NCAR and partner organizations are making significant headway in predicting the behavior of the atmosphere on a variety of fronts, including:

improving weather forecasts

advancing renewable energy capabilities

helping satellites avoid space debris

estimating the risk of a crop slowdown due to climate change

These advances are summarized in short online features now published each week on our AtmosNews website: http://www.ucar.edu/atmosnews.

To get a jump on stories about new research, we invite you to sign up for our concise weekly ...

Single gene controls jet lag

2014-08-13

LA JOLLA–Scientists at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies have identified a gene that regulates sleep and wake rhythms.

The discovery of the role of this gene, called Lhx1, provides scientists with a potential therapeutic target to help night-shift workers or jet lagged travelers adjust to time differences more quickly. The results, published in eLife, can point to treatment strategies for sleep problems caused by a variety of disorders.

"It's possible that the severity of many dementias comes from sleep disturbances," says Satchidananda Panda, a Salk associate ...

NIH-led scientists boost potential of passive immunization against HIV

2014-08-13

WHAT:

Scientists are pursuing injections or intravenous infusions of broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies (bNAbs) as a strategy for preventing HIV infection. This technique, called passive immunization, has been shown to protect monkeys from a monkey form of HIV called simian human immunodeficiency virus, or SHIV. To make passive immunization a widely feasible HIV prevention option for people, scientists want to modify bNAbs such that a modest amount of them is needed only once every few months.

To that end, an NIH-led team of scientists has mutated the powerful anti-HIV ...

Foreshock series controls earthquake rupture

2014-08-13

A long lasting foreshock series controlled the rupture process of this year's great earthquake near Iquique in northern Chile. The earthquake was heralded by a three quarter year long foreshock series of ever increasing magnitudes culminating in a Mw 6.7 event two weeks before the mainshock. The mainshock (magnitude 8.1) finally broke on April 1st a central piece out of the most important seismic gap along the South American subduction zone. An international research team under leadership of the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences now revealed that the Iquique earthquake ...

Cell discovery brings blood disorder cure closer

2014-08-13

A cure for a range of blood disorders and immune diseases is in sight, according to scientists who have unravelled the mystery of stem cell generation.

The Australian study, led by researchers at the Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute (ARMI) at Monash University and the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, is published today in Nature. It identifies for the first time mechanisms in the body that trigger hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) production.

Found in the bone marrow and in umbilical cord blood, HSCs are critically important because they can replenish the ...

University of Tennessee research uncovers forces that hold gravity-defying near-earth asteroid together

2014-08-13

Researchers at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, have made a novel discovery that may potentially protect the world from future collisions with asteroids.

The team studied near-Earth asteroid 1950 DA and discovered that the body, which rotates so quickly it defies gravity, is held together by cohesive forces called van der Waals, never detected before on an asteroid.

The findings, published in this week's edition of the science journal Nature, have potential implications for defending our planet from a massive asteroid impact.

Previous research has shown that ...

New test reveals purity of graphene

2014-08-13

Graphene may be tough, but those who handle it had better be tender. The environment surrounding the atom-thick carbon material can influence its electronic performance, according to researchers at Rice and Osaka universities who have come up with a simple way to spot contaminants.

Because it's so easy to accidently introduce impurities into graphene, labs led by physicists Junichiro Kono of Rice and Masayoshi Tonouchi of Osaka's Institute of Laser Engineering discovered a way to detect and identify out-of-place molecules on its surface through terahertz spectroscopy.

They ...