(Press-News.org) It has been speculated that soil-dwelling parasitic worms use their sense of smell to find suitable hosts for infection. Research published on August 14th in PLOS Pathogens comparing odor-driven behaviors in different roundworm species reveals that olfactory preferences reflect host specificity rather than species relatedness, suggesting that olfaction indeed plays an important role in host location.

To study worm olfaction, Elissa Hallem, from the University of California Los Angeles, USA, and colleagues examined the host-seeking strategies and sensory behaviors of different roundworms. They compared three skin-penetrating parasitic species, including Strongloides stercoralis, the threadworm that causes the serious and common disease strongyloidiasis, with five other worm species of diverse lifestyles and ecological niches.

Some of the species, including Str. stercoralis are "cruisers" that are highly mobile and actively search for hosts, others are "ambushers" that seem to wait for passing hosts and display little unstimulated movement, and some use an intermediate strategy. All of the worm species studied, regardless of host-seeking strategy, react to different odors. They are attracted by some smells and repelled by others, and each species has a unique odor response profile. Str. stercoralis, at its infective juvenile stage, for example, is attracted to odors of human skin and sweat. And Haemonchus contortus, which infects cattle, is attracted by odors of grass and cow breath, which puts it in a perfect position to enter the digestive tract of its host.

Comparing these profiles, the researchers found that those of species with similar hosts were most similar, and this was true even when the species were not closely related. The fact that host specificity rather than relatedness predicts similar olfactory preferences suggests that a worm's sense of smell does indeed play an important role in host location and selection.

The researchers suggest that "the identification of odorants that attract or repel Str. stercoralis and other parasitic nematodes lays a foundation for the design of targeted traps or repellents, which could have broad implications for nematode control". And as "nearly all of the attractants identified for Str. stercoralis also attract anthropophilic mosquitoes [those that feed on humans]" and "Str. stercoralis and disease-causing mosquitoes are co-endemic throughout the world", they say their results "raise the possibility of designing traps that are effective against both".

INFORMATION:

Please contact plospathogens@plos.org if you would like more information about our content and specific topics of interest.

All works published in PLOS Pathogens are open access, which means that everything is immediately and freely available. Use this URL in your coverage to provide readers access to the paper upon publication:

http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal. ppat.1004305 (Link goes live upon article publication)

Contact:

Elissa Hallem

e-mail: ehallem@microbio.ucla.edu

phone: +1.310.825.1778

Authors and Affiliations:

Michelle L. Castelletto, University of California, Los Angeles, USA

Spencer S. Gang, University of California, Los Angeles, USA

Ryo P. Okubo, University of California, Los Angeles, USA

Anastassia A. Tselikova, University of California, Los Angeles, USA

Edward G. Platzer, University of California, Riverside, USA

James B. Lok, University of Pennsylvania,USA

Elissa A. Hallem, University of California, Los Angeles, USA

Thomas J. Nolan, University of Pennsylvania,USA

Citation: Castelletto ML, Gang SS, Okubo RP, Tselikova AA, Nolan TJ, et al. (2014) Diverse Host-Seeking Behaviors of Skin-Penetrating Nematodes. PLoS Pathog 10(8): e1004305. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004305

Parasitic worms sniff out their victims as 'cruisers' or 'ambushers'

2014-08-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Drugs that flush out HIV may impair killer T cells, possibly hindering HIV eradication

2014-08-14

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors have shown promise in "flushing out" HIV from latently infected cells, potentially exposing the reservoirs available for elimination by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), also called killer T cells. However, findings published on August 14th in PLOS Pathogens now suggest that treatment with HDAC inhibitors might suppress CTL activity and therefore compromise the "kill" part of a two-pronged "flush-and-kill" HIV eradication strategy.

At least three different HDAC inhibitors, romidepsin, panobinostat, and SAHA, are under investigation as ...

Plants may use newly discovered language to communicate, Virginia Tech scientist discovers

2014-08-14

VIDEO:

This time-lapse video shows how the parasitic plant dodder attacks tomatoes. But beyond stealing nutrients from the host plants, a Virginia Tech researcher has discovered that the two plants also...

Click here for more information.

A Virginia Tech scientist has discovered a potentially new form of plant communication, one that allows them to share an extraordinary amount of genetic information with one another.

The finding by Jim Westwood, a professor of plant pathology, ...

Human contribution to glacier mass loss on the increase

2014-08-14

This news release is available in German.

The ongoing global glacier retreat causes rising sea-levels, changing seasonal water availability and increasing geo-hazards. While melting glaciers have become emblematic of anthropogenic climate change, glacier extent responds very slowly to climate changes. "Typically, it takes glaciers decades or centuries to adjust to climate changes," says climate researcher Ben Marzeion from the Institute of Meteorology and Geophysics of the University of Innsbruck. The global retreat of glaciers observed today started around the middle ...

Seven tiny grains captured by Stardust likely visitors from interstellar space

2014-08-14

Since 2006, when NASA's Stardust spacecraft delivered its aerogel and aluminum foil dust collectors to Earth, a team of scientists has combed through the collectors in search of rare, microscopic particles of interstellar dust.

The team now reports that they have found seven dust motes that probably came from outside our solar system, perhaps created in a supernova explosion millions of years ago and altered by eons of exposure to the extremes of space. They would be the first confirmed samples of contemporary interstellar dust.

"They are very precious particles," ...

Memories of errors foster faster learning

2014-08-14

Using a deceptively simple set of experiments, researchers at Johns Hopkins have learned why people learn an identical or similar task faster the second, third and subsequent time around. The reason: They are aided not only by memories of how to perform the task, but also by memories of the errors made the first time.

"In learning a new motor task, there appear to be two processes happening at once," says Reza Shadmehr, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "One is the learning of the motor ...

Harnessing the power of bacteria's sophisticated immune system

2014-08-14

Bacteria's ability to destroy viruses has long puzzled scientists, but researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health say they now have a clear picture of the bacterial immune system and say its unique shape is likely why bacteria can so quickly recognize and destroy their assailants.

The researchers drew what they say is the first-ever picture of the molecular machinery, known as Cascade, which stands guard inside bacterial cells. To their surprise, they found it contains a two-strand, unencumbered structure that resembles a ladder, freeing it to ...

Message to parents: Babies don't 'start from scratch'

2014-08-14

There's now overwhelming evidence that a child's future health is influenced by more than just their parents' genetic material, and that children born of unhealthy parents will already be pre-programmed for greater risk of poor health, according to University of Adelaide researchers.

In a feature paper called "Parenting from before conception" published in today's issue of the top international journal Science, researchers at the University's Robinson Research Institute say environmental factors prior to conception have more influence on the child's future than previously ...

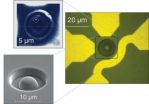

A self-organizing thousand-robot swarm

2014-08-14

Cambridge, Mass. – August 14, 2014 – The first thousand-robot flash mob has assembled at Harvard University.

"Form a sea star shape," directs a computer scientist, sending the command to 1,024 little bots simultaneously via an infrared light. The robots begin to blink at one another and then gradually arrange themselves into a five-pointed star. "Now form the letter K."

The 'K' stands for Kilobots, the name given to these extremely simple robots, each just a few centimeters across, standing on three pin-like legs. Instead of one highly-complex robot, a "kilo" of robots ...

Molecular engineers record an electron's quantum behavior

2014-08-14

A team of researchers led by the University of Chicago has developed a technique to record the quantum mechanical behavior of an individual electron contained within a nanoscale defect in diamond. Their technique uses ultrafast pulses of laser light both to control the defect's entire quantum state and observe how that single electron state changes over time. The work appears in this week's online Science Express and will be published in print later this month in Science.

This research contributes to the emerging science of quantum information processing, which demands ...

Mysteries of space dust revealed

2014-08-14

The first analysis of space dust collected by a special collector onboard NASA's Stardust mission and sent back to Earth for study in 2006 suggests the tiny specks, which likely originated from beyond our solar system, are more complex in composition and structure than previously imagined.

The analysis, completed at a number of facilities including the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (Berkeley Lab) opens a door to studying the origins of the solar system and possibly the origin of life itself.

"Fundamentally, the solar system and everything ...