(Press-News.org) Cold Spring Harbor, NY – With three billion letters in the human genome, it seems hard to believe that adding a DNA base here or removing a DNA base there could have much of an effect on our health. In fact, such insertions and deletions can dramatically alter biological function, leading to diseases from autism to cancer. Still, it is has been difficult to detect these mutations. Now, a team of scientists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has devised a new way to analyze genome sequences that pinpoints so-called insertion and deletion mutations (known as "indels") in genomes of people with diseases such as autism, obsessive-compulsive disorder and Tourette syndrome.

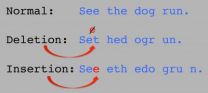

The letters in the human genome carry instructions to make proteins, via a three-letter code. Each trio spells out a "word;" the words are then strung together in a sentence to build a specific protein. If a letter is accidentally inserted or deleted from our genome, the three-letter code shifts a notch, causing all of the subsequent words to be misspelled. These "frameshift" mutations cause the protein sentence to become unintelligible. Loss of a single protein can have devastating effects for cells, leading to dysfunction and sometimes to serious diseases.

DNA insertions and deletions vary in length and sequence. Each indel can range in size from one DNA letter to thousands, and they are often highly repetitive. Their variability has made it challenging to identify indels, despite major advancements in genome sequencing technology. They are, in effect, regions of the genome that have remained hidden from view as researchers search for the mutations that cause disease.

A team of CSHL scientists, including Assistant Professors Mike Schatz, Gholson Lyon, and Ivan Iossifov, and Professor Michael Wigler, has devised a way to mine existing genomic datasets for indel mutations. The method, which they call Scalpel, begins by grouping together all of the sequences from a given genomic region. Scalpel – a computer formula, or algorithm – then creates a new sequence alignment for that area, much like piecing together parts of a puzzle.

"These indels are like very fine cuts to the genome – places where DNA is inserted or deleted – and Scalpel provides us with a computational lens to zoom in and see precisely where the cuts occur," says Schatz, a quantitative biologist. Such information is critical to understand the mutations that cause disease. In work published today in Nature Methods, the team used Scalpel to search for indels in patient samples. Lyon, a CSHL researcher who is also a practicing psychiatrist, worked with his team to analyze a patient with severe Tourette syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder, identifying and validating more than a thousand indels to demonstrate the accuracy of the method.

The CSHL team performed a similar analysis to search for indels that are associated with autism. They explored a dataset of 593 families from the Simons Simplex Collection, a group composed entirely of families with one affected child but no other family members with the disorder. While the researchers discovered a total of 3.3 million indels across the 593 families, most appeared to be relatively harmless. Still, a few dozen mutations stood out to be specifically associated with autism. "All this adds to our body of knowledge about the spontaneous mutations that cause autism," says Schatz.

But the tool can be applied much more broadly. "We are collaborating with plant scientists, cancer biologists, and others, looking for indels," says Schatz. "This is a powerful tool, and we are looking forward to revealing new pieces of the genome that make a difference, throughout the tree of life."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health, US National Science Foundation, the CSHL Cancer Center Support Grant, the Stanley Institute for Cognitive Genomics, and the Simons Foundation.

"Accurate de novo and transmitted indel detection in exome-capture data using microassembly" appears online in Nature Methods on August 17, 2014. The authors are: Giuseppe Narzisi, Jason O'Rawe, Ivan Iossifov, Han Fang, Yoon-ha Lee, Zihua Wang, Yiyang Wu, Gholson Lyon, Michael Wigler, and Michael Schatz.

The paper can be obtained online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3069

About Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Founded in 1890, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has shaped contemporary biomedical research and education with programs in cancer, neuroscience, plant biology and quantitative biology. CSHL is ranked number one in the world by Thomson Reuters for the impact of its research in molecular biology and genetics. The Laboratory has been home to eight Nobel Prize winners. Today, CSHL's multidisciplinary scientific community is more than 600 researchers and technicians strong and its Meetings & Courses program hosts more than 12,000 scientists from around the world each year to its Long Island campus and its China center. For more information, visit http://www.cshl.edu.

A shift in the code: New method reveals hidden genetic landscape

Scientists develop algorithm to uncover genomic insertions and deletions involved in autism, OCD

2014-08-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New home for an 'evolutionary misfit'

2014-08-17

One of the most bizarre-looking fossils ever found - a worm-like creature with legs, spikes and a head difficult to distinguish from its tail – has found its place in the evolutionary Tree of Life, definitively linking it with a group of modern animals for the first time.

The animal, known as Hallucigenia due to its otherworldly appearance, had been considered an 'evolutionary misfit' as it was not clear how it related to modern animal groups. Researchers from the University of Cambridge have discovered an important link with modern velvet worms, also known as onychophorans, ...

Stem cells reveal how illness-linked genetic variation affects neurons

2014-08-17

VIDEO:

Human neurons firing

Click here for more information.

A genetic variation linked to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and severe depression wreaks havoc on connections among neurons in the developing brain, a team of researchers reports. The study, led by Guo-li Ming, M.D., Ph.D., and Hongjun Song, Ph.D., of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and described online Aug. 17 in the journal Nature, used stem cells generated from people with and without mental illness ...

New Stanford research sheds light on how children's brains memorize facts

2014-08-17

As children learn basic arithmetic, they gradually switch from solving problems by counting on their fingers to pulling facts from memory. The shift comes more easily for some kids than for others, but no one knows why.

Now, new brain-imaging research gives the first evidence drawn from a longitudinal study to explain how the brain reorganizes itself as children learn math facts. A precisely orchestrated group of brain changes, many involving the memory center known as the hippocampus, are essential to the transformation, according to a study from the Stanford University ...

Suspect gene corrupts neural connections

2014-08-17

Researchers have long suspected that major mental disorders are genetically-rooted diseases of synapses – the connections between neurons. Now, investigators supported in part by the National Institutes of Health have demonstrated in patients' cells how a rare mutation in a suspect gene disrupts the turning on and off of dozens of other genes underlying these connections.

"Our results illustrate how genetic risk, abnormal brain development and synapse dysfunction can corrupt brain circuitry at the cellular level in complex psychiatric disorders," explained Hongjun Song, ...

Stuck in neutral: Brain defect traps schizophrenics in twilight zone

2014-08-17

People with schizophrenia struggle to turn goals into actions because brain structures governing desire and emotion are less active and fail to pass goal-directed messages to cortical regions affecting human decision-making, new research reveals.

Published in Biological Psychiatry, the finding by a University of Sydney research team is the first to illustrate the inability to initiate goal-directed behaviour common in people with schizophrenia.

The finding may explain why people with schizophrenia have difficulty achieving real-world goals such as making friends, completing ...

Virginity pledges for men can lead to sexual confusion -- even after the wedding day

2014-08-17

Bragging of sexual conquests, suggestive jokes and innuendo, and sexual one-upmanship can all be a part of demonstrating one's manhood, especially for young men eager to exert their masculinity.

But how does masculinity manifest itself among young men who have pledged sexual abstinence before marriage? How do they handle sexual temptation, and what sorts of challenges crop up once they're married?

"Sexual purity and pledging abstinence are most commonly thought of as feminine, something girls and young women promise before marriage," said Sarah Diefendorf, a sociology ...

Study finds range of skills students taught in school linked to race and class size

2014-08-17

SAN FRANCISCO -- Pressure to meet national education standards may be the reason states with significant populations of African-American students and those with larger class sizes often require children to learn fewer skills, finds a University of Kansas researcher.

"The skills students are expected to learn in schools are not necessarily universal," said Argun Saatcioglu, a KU associate professor of education and courtesy professor of sociology.

In effort to increase their test scores and, therefore, avoid the negative consequences of failing to meet the federal standards ...

Study suggests federal law to combat use of 'club drugs' has done more harm than good

2014-08-17

SAN FRANCISCO — A federal law enacted to combat the use of "club drugs" such as Ecstasy — and today's variation known as Molly — has failed to reduce the drugs' popularity and, instead, has further endangered users by hampering the use of measures to protect them.

University of Delaware sociology professor Tammy L. Anderson makes that case in a paper she will present at the 109th Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association. The paper, which has been accepted for publication this fall in the American Sociological Association journal Contexts, examines the unintended ...

Risky situations increase women's anxiety, hurt their performance compared to men

2014-08-17

SAN FRANCISCO — Risky situations increase anxiety for women but not for men, leading women to perform worse under these circumstances, finds a study to be presented at the 109th Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association.

"On the surface, risky situations may not appear to be particularly disadvantageous to women, but these findings suggest otherwise," said study author Susan R. Fisk, a doctoral candidate in sociology at Stanford University, who defines a risky situation as any setting with an uncertain outcome in which there can be both positive or negative ...

Most temporary workers from Mexico no better off than undocumented workers

2014-08-17

SAN FRANCISCO -- Many politicians see the temporary worker program in the U.S. as a solution to undocumented immigration from Mexico. But an Indiana University study finds that these legal workers earn no more than undocumented immigrants, who unlike their legal counterparts can improve their situation by changing jobs or negotiating for better pay.

"Just because temporary workers are legally present in the country does not mean that they will have better jobs or wages than undocumented workers," said Lauren Apgar, lead researcher of the study "Temporary Worker Advantages? ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists reveal our best- and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

Cleaner fish show intelligence typical of mammals

AABNet and partners launch landmark guide on the conservation of African livestock genetic resources and sustainable breeding strategies

Produce hydrogen and oxygen simultaneously from a single atom! Achieve carbon neutrality with an 'All-in-one' single-atom water electrolysis catalyst

Sleep loss linked to higher atrial fibrillation risk in working-age adults

Visible light-driven deracemization of α-aryl ketones synergistically catalyzed by thiophenols and chiral phosphoric acid

Most AI bots lack basic safety disclosures, study finds

How competitive gaming on discord fosters social connections

CU Anschutz School of Medicine receives best ranking in NIH funding in 20 years

Mayo Clinic opens patient information office in Cayman Islands

Phonon lasers unlock ultrabroadband acoustic frequency combs

Babies with an increased likelihood of autism may struggle to settle into deep, restorative sleep, according to a new study from the University of East Anglia.

National Reactor Innovation Center opens Molten Salt Thermophysical Examination Capability at INL

International Progressive MS Alliance awards €6.9 million to three studies researching therapies to address common symptoms of progressive MS

Can your soil’s color predict its health?

Biochar nanomaterials could transform medicine, energy, and climate solutions

Turning waste into power: scientists convert discarded phone batteries and industrial lignin into high-performance sodium battery materials

PhD student maps mysterious upper atmosphere of Uranus for the first time

Idaho National Laboratory to accelerate nuclear energy deployment with NVIDIA AI through the Genesis Mission

Blood test could help guide treatment decisions in germ cell tumors

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

“Cyborg” pancreatic organoids can monitor the maturation of islet cells

Technique to extract concepts from AI models can help steer and monitor model outputs

Study clarifies the cancer genome in domestic cats

Crested Spinosaurus fossil was aquatic, but lived 1,000 kilometers from the Tethys Sea

MULTI-evolve: Rapid evolution of complex multi-mutant proteins

A new method to steer AI output uncovers vulnerabilities and potential improvements

Why some objects in space look like snowmen

Flickering glacial climate may have shaped early human evolution

First AHA/ACC acute pulmonary embolism guideline: prompt diagnosis and treatment are key

[Press-News.org] A shift in the code: New method reveals hidden genetic landscapeScientists develop algorithm to uncover genomic insertions and deletions involved in autism, OCD