(Press-News.org) NEW YORK, NY (August 17, 2014) —Researchers at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) have identified the immune cells responsible for destroying hair follicles in people with alopecia areata, a common autoimmune disease that causes hair loss, and have tested an FDA-approved drug that eliminated these immune cells and restored hair growth in a small number of patients.

The results appear in today's online issue of Nature Medicine.

In the paper, the researchers report initial results from an ongoing clinical trial of the drug, which has produced complete hair regrowth in several patients with moderate-to-severe alopecia areata. Data from three participants appear in the current paper; each patient experienced total hair regrowth within five months of the start of treatment.

"We've only begun testing the drug in patients, but if the drug continues to be successful and safe, it will have a dramatic positive impact on the lives of people with this disease," said Raphael Clynes, MD, PhD, who led the research, along with Angela M. Christiano, PhD, professor in the Departments of Dermatology and of Genetics and Development at CUMC.

Alopecia areata is a common autoimmune disease that causes disfiguring hair loss. The disease can occur at any age and affects men and women equally. Hair is often lost in patches on the scalp, but in some patients it also causes loss of facial and body hair. There are no known treatments that can completely restore hair, and patients with the disease experience significant psychological stress and emotional suffering.

Scientists have known for decades that hair loss in alopecia areata occurs when cells from the immune system surround and attack the base of the hair follicle, causing the hair to fall out and enter a dormant state. Until now, the specific type of cell responsible for the attack had been a mystery. A major clue was uncovered four years ago in Dr. Christiano's genetic study of more than 1,000 patients with the disease. That study suggested that a "danger signal" in the hair follicles of patients—not previously linked to alopecia areata—attracts the immune cells to the follicle and sparks the attack.

The current paper describes how the team first studied mice with the disease, then tracked backward from the danger signal to identify the specific set of T cells responsible for attacking the hair follicles. Further investigation of mouse and patient cells revealed how the T cells are instructed to attack and identified several key immune pathways that could be targeted by a new class of drugs, known as JAK inhibitors.

Two FDA-approved JAK inhibitors tested separately by the researchers—ruxolitinib and tofacitinib—were able to block these immune pathways and stop the attack on the hair follicles. In mice with extensive hair loss from the disease, both drugs completely restored the animals' hair within 12 weeks. Each drug's effect was also long-lasting, as the new hair persisted for several months after stopping treatment.

Together with Julian Mackay-Wiggan, MD, MS, director of the Clinical Research Unit in the Department of Dermatology at CUMC and a practicing dermatologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia who treats patients with multiple types of hair loss, the researchers rapidly initiated a small open-label clinical trial of ruxolitinib—which is FDA approved for the treatment of a blood disorder—in patients with moderate-to-severe alopecia areata (with more than 30 percent hair loss). In three of the trial's early participants, ruxolitinib completely restored hair growth within four to five months of starting treatment, and the attacking T cells disappeared from the scalp.

"We still need to do more testing to establish that ruxolitinib should be used in alopecia areata, but this is exciting news for patients and their physicians," Dr. Clynes said. "This disease has been completely understudied—until now, only two small clinical trials evaluating targeted therapies in alopecia areata have been performed, largely because of the lack of mechanistic insight into it."

"The timeline of moving from genetic findings to positive results in a clinical trial in only four years is astoundingly fast and speaks to this team's ability to perform translational science of the highest caliber," said David Bickers, MD, the Carl Truman Nelson Professor of Dermatology and chair of the Department of Dermatology at CUMC and dermatologist-in-chief at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia. A practicing dermatologist who cares for many patients with alopecia areata himself, Dr. Bickers said, "There are few tools in the arsenal for the treatment of alopecia areata that have any demonstrated efficacy. This is a major step forward in improving the standard of care for patients suffering from this devastating disease."

But as Dr. Christiano knows firsthand from her own personal experience with the disease, alopecia areata is too often dismissed as simply an appearance-altering disease. "Nothing could be further from the truth," she said. "Patients with alopecia areata are suffering profoundly, and these findings mark a significant step forward for them. The team is fully committed to advancing new therapies for patients with a vast unmet need."

INFORMATION:

The paper is titled, "Alopecia Areata is Driven by Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes and is Reversed by JAK Inhibition." The other contributors are Luzhou Xing, Zhenpeng Dai, Ali Jabbari, Jane E. Cerise, Claire Higgins, Weijuan Gong, Annemieke de Jong, Sivan Harel, Gina M. DeStefano, Lisa Rothman, Pallavi Singh, Lynn Petukhova, all at CUMC.

This work was supported in part by USPHS NIH/NIAMS R01AR056016 (to A.M.C.) and R21AR061881 (to A.M.C and R.C.), R01CA164309 and a Shared Instrumentation Grant for the LSR II Flow Cytometer (S10RR027050) to R.C., the Columbia University Skin Disease Research Center (P30AR044535), as well as the Locks of Love Foundation and the Alopecia Areata Initiative. J.E.C. is supported by (T32GM082271) Medical Genetics Training Grant (to A.M.C.). A.J., C.H., S.H., and A.D. are recipients of Career Development Awards from the Dermatology Foundation, and A.J. is also supported by the Louis V.Gerstner, Jr. Scholars Program.

Dr. Clynes worked on this study while an associate professor in the departments of Pathology and Cell Biology, Medicine, and Dermatology at CUMC, and a medical oncologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia. Dr. Clynes is now employed by Bristol-Myers Squibb, which was not involved in this research.

Columbia University has filed for intellectual property protection on the treatment of alopecia areata with small-molecule JAK inhibitors (PCT/US2011/059029 and PCT/US2013/034688).

See animation: http://newsroom.cumc.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/hairmorph.gif

See video: http://player.vimeo.com/video/103265367?title=0&byline=0&portrait=0&color=a4bbd8

About Columbia University Medical Center

Columbia University Medical Center provides international leadership in basic, preclinical, and clinical research; medical and health sciences education; and patient care. The medical center trains future leaders and includes the dedicated work of many physicians, scientists, public health professionals, dentists, and nurses at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, the Mailman School of Public Health, the College of Dental Medicine, the School of Nursing, the biomedical departments of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and allied research centers and institutions. Columbia University Medical Center is home to the largest medical research enterprise in New York City and State and one of the largest faculty medical practices in the Northeast. For more information, visit cumc.columbia.edu or columbiadoctors.org.

FDA-approved drug restores hair in patients with Alopecia Areata

Alopecia areata is a common autoimmune disease that causes disfiguring hair loss

2014-08-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Fascinating rhythm: Light pulses illuminate a rare black hole

2014-08-17

The universe has so many black holes that it's impossible to count them all. There may be 100 million of these intriguing astral objects in our galaxy alone. Nearly all black holes fall into one of two classes: big, and colossal. Astronomers know that black holes ranging from about 10 times to 100 times the mass of our sun are the remnants of dying stars, and that supermassive black holes, more than a million times the mass of the sun, inhabit the centers of most galaxies.

But scattered across the universe like oases in a desert are a few apparent black holes of a more ...

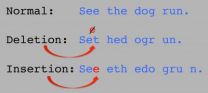

A shift in the code: New method reveals hidden genetic landscape

2014-08-17

Cold Spring Harbor, NY – With three billion letters in the human genome, it seems hard to believe that adding a DNA base here or removing a DNA base there could have much of an effect on our health. In fact, such insertions and deletions can dramatically alter biological function, leading to diseases from autism to cancer. Still, it is has been difficult to detect these mutations. Now, a team of scientists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has devised a new way to analyze genome sequences that pinpoints so-called insertion and deletion mutations (known as "indels") ...

New home for an 'evolutionary misfit'

2014-08-17

One of the most bizarre-looking fossils ever found - a worm-like creature with legs, spikes and a head difficult to distinguish from its tail – has found its place in the evolutionary Tree of Life, definitively linking it with a group of modern animals for the first time.

The animal, known as Hallucigenia due to its otherworldly appearance, had been considered an 'evolutionary misfit' as it was not clear how it related to modern animal groups. Researchers from the University of Cambridge have discovered an important link with modern velvet worms, also known as onychophorans, ...

Stem cells reveal how illness-linked genetic variation affects neurons

2014-08-17

VIDEO:

Human neurons firing

Click here for more information.

A genetic variation linked to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and severe depression wreaks havoc on connections among neurons in the developing brain, a team of researchers reports. The study, led by Guo-li Ming, M.D., Ph.D., and Hongjun Song, Ph.D., of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and described online Aug. 17 in the journal Nature, used stem cells generated from people with and without mental illness ...

New Stanford research sheds light on how children's brains memorize facts

2014-08-17

As children learn basic arithmetic, they gradually switch from solving problems by counting on their fingers to pulling facts from memory. The shift comes more easily for some kids than for others, but no one knows why.

Now, new brain-imaging research gives the first evidence drawn from a longitudinal study to explain how the brain reorganizes itself as children learn math facts. A precisely orchestrated group of brain changes, many involving the memory center known as the hippocampus, are essential to the transformation, according to a study from the Stanford University ...

Suspect gene corrupts neural connections

2014-08-17

Researchers have long suspected that major mental disorders are genetically-rooted diseases of synapses – the connections between neurons. Now, investigators supported in part by the National Institutes of Health have demonstrated in patients' cells how a rare mutation in a suspect gene disrupts the turning on and off of dozens of other genes underlying these connections.

"Our results illustrate how genetic risk, abnormal brain development and synapse dysfunction can corrupt brain circuitry at the cellular level in complex psychiatric disorders," explained Hongjun Song, ...

Stuck in neutral: Brain defect traps schizophrenics in twilight zone

2014-08-17

People with schizophrenia struggle to turn goals into actions because brain structures governing desire and emotion are less active and fail to pass goal-directed messages to cortical regions affecting human decision-making, new research reveals.

Published in Biological Psychiatry, the finding by a University of Sydney research team is the first to illustrate the inability to initiate goal-directed behaviour common in people with schizophrenia.

The finding may explain why people with schizophrenia have difficulty achieving real-world goals such as making friends, completing ...

Virginity pledges for men can lead to sexual confusion -- even after the wedding day

2014-08-17

Bragging of sexual conquests, suggestive jokes and innuendo, and sexual one-upmanship can all be a part of demonstrating one's manhood, especially for young men eager to exert their masculinity.

But how does masculinity manifest itself among young men who have pledged sexual abstinence before marriage? How do they handle sexual temptation, and what sorts of challenges crop up once they're married?

"Sexual purity and pledging abstinence are most commonly thought of as feminine, something girls and young women promise before marriage," said Sarah Diefendorf, a sociology ...

Study finds range of skills students taught in school linked to race and class size

2014-08-17

SAN FRANCISCO -- Pressure to meet national education standards may be the reason states with significant populations of African-American students and those with larger class sizes often require children to learn fewer skills, finds a University of Kansas researcher.

"The skills students are expected to learn in schools are not necessarily universal," said Argun Saatcioglu, a KU associate professor of education and courtesy professor of sociology.

In effort to increase their test scores and, therefore, avoid the negative consequences of failing to meet the federal standards ...

Study suggests federal law to combat use of 'club drugs' has done more harm than good

2014-08-17

SAN FRANCISCO — A federal law enacted to combat the use of "club drugs" such as Ecstasy — and today's variation known as Molly — has failed to reduce the drugs' popularity and, instead, has further endangered users by hampering the use of measures to protect them.

University of Delaware sociology professor Tammy L. Anderson makes that case in a paper she will present at the 109th Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association. The paper, which has been accepted for publication this fall in the American Sociological Association journal Contexts, examines the unintended ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Industrial research labs were invented in Europe but made the U.S. a tech superpower

Enzymes work as Maxwell's demon by using memory stored as motion

Methane’s missing emissions: The underestimated impact of small sources

Beating cancer by eating cancer

How sleep disruption impairs social memory: Oxytocin circuits reveal mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities

Natural compound from pomegranate leaves disrupts disease-causing amyloid

A depression treatment that once took eight weeks may work just as well in one

New study calls for personalized, tiered approach to postpartum care

The hidden breath of cities: Why we need to look closer at public fountains

Rewetting peatlands could unlock more effective carbon removal using biochar

Microplastics discovered in prostate tumors

ACES marks 150 years of the Morrow Plots, our nation's oldest research field

Physicists open door to future, hyper-efficient ‘orbitronic’ devices

$80 million supports research into exceptional longevity

Why the planet doesn’t dry out together: scientists solve a global climate puzzle

Global greening: The Earth’s green wave is shifting

You don't need to be very altruistic to stop an epidemic

Signs on Stone Age objects: Precursor to written language dates back 40,000 years

MIT study reveals climatic fingerprints of wildfires and volcanic eruptions

A shift from the sandlot to the travel team for youth sports

Hair-width LEDs could replace lasers

The hidden infections that refuse to go away: how household practices can stop deadly diseases

Ochsner MD Anderson uses groundbreaking TIL therapy to treat advanced melanoma in adults

A heatshield for ‘never-wet’ surfaces: Rice engineering team repels even near-boiling water with low-cost, scalable coating

Skills from being a birder may change—and benefit—your brain

Waterloo researchers turning plastic waste into vinegar

Measuring the expansion of the universe with cosmic fireworks

How horses whinny: Whistling while singing

US newborn hepatitis B virus vaccination rates

When influencers raise a glass, young viewers want to join them

[Press-News.org] FDA-approved drug restores hair in patients with Alopecia AreataAlopecia areata is a common autoimmune disease that causes disfiguring hair loss