(Press-News.org) The presence of Clostridia, a common class of gut bacteria, protects against food allergies, a new study in mice finds. By inducing immune responses that prevent food allergens from entering the bloodstream, Clostridia minimize allergen exposure and prevent sensitization – a key step in the development of food allergies. The discovery points toward probiotic therapies for this so-far untreatable condition, report scientists from the University of Chicago, Aug 25 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Although the causes of food allergy – a sometimes deadly immune response to certain foods – are unknown, studies have hinted that modern hygienic or dietary practices may play a role by disturbing the body's natural bacterial composition. In recent years, food allergy rates among children have risen sharply – increasing approximately 50 percent between 1997 and 2011 – and studies have shown a correlation to antibiotic and antimicrobial use.

"Environmental stimuli such as antibiotic overuse, high fat diets, caesarean birth, removal of common pathogens and even formula feeding have affected the microbiota with which we've co-evolved," said study senior author Cathryn Nagler, PhD, Bunning Food Allergy Professor at the University of Chicago. "Our results suggest this could contribute to the increasing susceptibility to food allergies."

To test how gut bacteria affect food allergies, Nagler and her team investigated the response to food allergens in mice. They exposed germ-free mice (born and raised in sterile conditions to have no resident microorganisms) and mice treated with antibiotics as newborns (which significantly reduces gut bacteria) to peanut allergens. Both groups of mice displayed a strong immunological response, producing significantly higher levels of antibodies against peanut allergens than mice with normal gut bacteria.

This sensitization to food allergens could be reversed, however, by reintroducing a mix of Clostridia bacteria back into the mice. Reintroduction of another major group of intestinal bacteria, Bacteroides, failed to alleviate sensitization, indicating that Clostridia have a unique, protective role against food allergens.

Closing the door

To identify this protective mechanism, Nagler and her team studied cellular and molecular immune responses to bacteria in the gut. Genetic analysis revealed that Clostridia caused innate immune cells to produce high levels of interleukin-22 (IL-22), a signaling molecule known to decrease the permeability of the intestinal lining.

Antibiotic-treated mice were either given IL-22 or were colonized with Clostridia. When exposed to peanut allergens, mice in both conditions showed reduced allergen levels in their blood, compared to controls. Allergen levels significantly increased, however, after the mice were given antibodies that neutralized IL-22, indicating that Clostridia-induced IL-22 prevents allergens from entering the bloodstream.

"We've identified a bacterial population that protects against food allergen sensitization," Nagler said. "The first step in getting sensitized to a food allergen is for it to get into your blood and be presented to your immune system. The presence of these bacteria regulates that process." She cautions, however, that these findings likely apply at a population level, and that the cause-and-effect relationship in individuals requires further study.

While complex and largely undetermined factors such as genetics greatly affect whether individuals develop food allergies and how they manifest, the identification of a bacteria-induced barrier-protective response represents a new paradigm for preventing sensitization to food. Clostridia bacteria are common in humans and represent a clear target for potential therapeutics that prevent or treat food allergies. Nagler and her team are working to develop and test compositions that could be used for probiotic therapy and have filed a provisional patent.

"It's exciting because we know what the bacteria are; we have a way to intervene," Nagler said. "There are of course no guarantees, but this is absolutely testable as a therapeutic against a disease for which there's nothing. As a mom, I can imagine how frightening it must be to worry every time your child takes a bite of food."

"Food allergies affect 15 million Americans, including one in 13 children, who live with this potentially life-threatening disease that currently has no cure," said Mary Jane Marchisotto, senior vice president of research at Food Allergy Research & Education. "We have been pleased to support the research that has been conducted by Dr. Nagler and her colleagues at the University of Chicago."

INFORMATION:

The study, "Commensal bacteria protect against food allergen sensitization," was supported by Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE) and the University of Chicago Digestive Diseases Research Core Center. Additional authors include Andrew T. Stefka, Taylor Feehley, Prabhanshu Tripathi, Ju Qiu, Kathy D. McCoy, Sarkis K. Mazmanian, Melissa Y. Tjota, Goo-Young Seo, Severine Cao, Betty R. Theriault, Dionysios A. Antonopoulos, Liang Zhou, Eugene B. Chang and Yang-Xin Fu.

FARE

Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that seeks to find a cure for food allergies while keeping affected individuals safe and included. FARE does this by investing in world-class research that advances the treatment and understanding of the disease, providing evidence-based education and resources, undertaking advocacy at all levels of government and increasing awareness of food allergy as a serious public health issue.

The University of Chicago Medicine

The University of Chicago Medicine and Biological Sciences is one of the nation's leading academic medical institutions. It comprises the Pritzker School of Medicine, a top medical school in the nation; the University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division; and the University of Chicago Medical Center, which recently opened the Center for Care and Discovery, a $700 million specialty medical facility. Twelve Nobel Prize winners in physiology or medicine have been affiliated with the University of Chicago Medicine.

Gut bacteria that protect against food allergies identified

Common gut bacteria prevent sensitization to allergens in a mouse model for peanut allergy, paving the way for probiotic therapies to treat food allergies

2014-08-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Key to universal flu vaccine: Embrace the unfamiliar

2014-08-25

Vaccine researchers have developed a strategy aimed at generating broadly cross-reactive antibodies against the influenza virus: embrace the unfamiliar.

In recent years, researchers interested in a "universal flu vaccine" identified a region of the viral hemagglutinin protein called the stem or stalk, which doesn't mutate and change as much as other regions and could be the basis for a vaccine that is protective against a variety of flu strains.

In an Emory Vaccine Center study, human volunteers immunized against the avian flu virus H5N1 readily developed antibodies ...

SA's Taung Child's skull and brain not human-like in expansion

2014-08-25

The Taung Child, South Africa's premier hominin discovered 90 years ago by Wits University Professor Raymond Dart, never seizes to transform and evolve the search for our collective origins.

By subjecting the skull of the first australopith discovered to the latest technologies in the Wits University Microfocus X-ray Computed Tomography (CT) facility, researchers are now casting doubt on theories that Australopithecus africanus shows the same cranial adaptations found in modern human infants and toddlers – in effect disproving current support for the idea that this early ...

A long childhood feeds the hungry human brain

2014-08-25

EVANSTON, Ill. -- A five-year old's brain is an energy monster. It uses twice as much glucose (the energy that fuels the brain) as that of a full-grown adult, a new study led by Northwestern University anthropologists has found.

The study helps to solve the long-standing mystery of why human children grow so slowly compared with our closest animal relatives.

It shows that energy funneled to the brain dominates the human body's metabolism early in life and is likely the reason why humans grow at a pace more typical of a reptile than a mammal during childhood.

Results ...

Black carbon -- a major climate pollutant -- also linked to cardiovascular health

2014-08-25

Black carbon pollutants from wood smoke are known to trap heat near the earth's surface and warm the climate. A new study led by McGill Professor Jill Baumgartner suggests that black carbon may also increase women's risk of cardiovascular disease.

To investigate the effects of black carbon pollutants on the health of women cooking with traditional wood stoves, Baumgartner, a researcher at McGill's Institute for the Health and Social Policy, measured the daily exposure to different types of air pollutants, including black carbon, in 280 women in China's rural Yunnan province.

Baumgartner ...

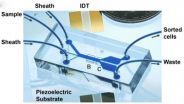

Tilted acoustic tweezers separate cells gently

2014-08-25

Precise, gentle and efficient cell separation from a device the size of a cell phone may be possible thanks to tilt-angle standing surface acoustic waves, according to a team of engineers.

"For biological testing we often need to do cell separation before analysis," said Tony Jun Huang, professor of engineering science and mechanics. "But if the separation process affects the integrity of the cells, damages them in any way, the diagnosis often won't work well."

Tilted-angle standing surface acoustic waves can separate cells using very small amounts of energy. Unlike ...

New biomarker highly promising for predicting breast cancer outcomes

2014-08-25

A protein named p66ShcA shows promise as a biomarker to identify breast cancers with poor prognoses, according to research published ahead of print in the journal Molecular and Cellular Biology.

Cancer is deadly in large part due to its ability to metastasize, to travel from one organ or tissue type to another and malignantly sprout anew. The vast majority of cancer deaths are associated with metastasis.

In breast cancer, a process called "epithelial to mesenchymal transition" aids metastasis. Epithelial cells line surfaces which come into contact with the environment, ...

Exposure to toxins makes great granddaughters more susceptible to stress

2014-08-25

Scientists have known that toxic effects of substances known as endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), found in both natural and human-made materials, can pass from one generation to the next, but new research shows that females with ancestral exposure to EDC may show especially adverse reactions to stress.

According to a new study by researchers from The University of Texas at Austin and Washington State University, male and female rats are affected differently by ancestral exposure to a common fungicide, vinclozolin. Female rats whose great grandparents were exposed ...

MU researchers discover protein's ability to inhibit HIV release

2014-08-25

COLUMBIA, Mo. — A family of proteins that promotes virus entry into cells also has the ability to block the release of HIV and other viruses, University of Missouri researchers have found.

"This is a surprising finding that provides new insights into our understanding of not only HIV infection, but also that of Ebola and other viruses," said Shan-Lu Liu, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor in the MU School of Medicine's Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology.

The study was recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Liu, the ...

Cancer-fighting drugs might also stop malaria early

2014-08-25

DURHAM, N.C. -- Scientists searching for new drugs to fight malaria have identified a number of compounds -- some of which are currently in clinical trials to treat cancer -- that could add to the anti-malarial arsenal.

Duke University assistant professor Emily Derbyshire and colleagues identified more than 30 enzyme-blocking molecules, called protein kinase inhibitors, that curb malaria before symptoms start.

By focusing on treatments that act early, before a person is infected and feels sick, the researchers hope to give malaria –- especially drug-resistant strains ...

Sweet! Glycoconjugates are more than the sum of their sugars

2014-08-25

There's a certain type of biomolecule built like a nano-Christmas tree. Called a glycoconjugate, it's many branches are bedecked with sugary ornaments.

It's those ornaments that get all the glory. That's because, according to conventional wisdom, the glycoconjugate's lowly "tree" basically holds the sugars in place as they do the important work of reacting with other molecules.

Now a chemist at Michigan Technological University has discovered that the tree itself—called the scaffold—is a good deal more than a simple prop.

"We had always thought that all the biological ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Gut bacteria that protect against food allergies identifiedCommon gut bacteria prevent sensitization to allergens in a mouse model for peanut allergy, paving the way for probiotic therapies to treat food allergies