(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Sakis play the group service game.

Click here for more information.

Scientists have long been searching for the factor that determines why humans often behave so selflessly. It was known that humans share this tendency with species of small Latin American primates of the family Callitrichidae (tamarins and marmosets), leading some to suggest that cooperative care for the young, which is ubiquitous in this family, was responsible for spontaneous helping behavior. But it was not so clear what other primate species do in this regard, because most studies were not comparable.

A group of researchers from Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Italy and Great Britain, headed by anthropologist Judith Burkart from the University of Zurich, therefore developed a novel approach they systematically applied to a great number of primate species. The results of the study have now been published in Nature Communications.

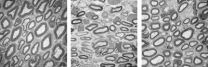

For their study, Burkart and her colleagues developed the new paradigm of group service, which examines spontaneous helping behavior in a standardized way. With the aid of a simple test apparatus, the researchers studied whether individuals from a particular primate species were prepared to provide other group members with a treat, even if this meant missing out themselves (see box). The scientists applied this standardized test to 24 social groups of 15 different primate species. They also examined whether and how kindergarten children aged between four and seven acted altruistically.

The researchers found that the willingness to provision others varies greatly from one primate species to the next. But there was a clear pattern, as summarized by Burkart: "Humans and callitrichid monkeys acted highly altruistically and almost always produced the treats for the other group members. Chimpanzees, one of our closest relatives, however, only did so sporadically." Similarly, most other primate species, including capuchins and macaques, only rarely pulled the lever to give another group member food, if at all – even though they have considerable cognitive skills.

Until now, many researchers assumed that spontaneous altruistic behavior in primates could be attributed to factors they would share with humans: advanced cognitive skills, large brains, high social tolerance, collective foraging or the presence of pair bonds or other strong social bonds. As Burkart's new data now reveal, however, none of these factors reliably predicts whether a primate species will be spontaneously altruistic or not. Instead, another factor that sets us humans apart from the great apes appears to be responsible. Says Burkart: "Spontaneous, altruistic behavior is exclusively found among species where the young are not only cared for by the mother, but also other group members such as siblings, fathers, grandmothers, aunts and uncles." This behavior is referred to technically as the "cooperative breeding" or "allomaternal care."

The significance of this study goes beyond identifying the roots of our altruism. Cooperative behavior also favored the evolution of our exceptional cognitive abilities. During development, human children gradually construct their cognitive skills based on extensive selfless social inputs from caring parents and other helpers, and the researchers believe that it is this new mode of caring that also put our ancestors on the road to our cognitive excellence. This study may, therefore, have just identified the foundation for the process that made us human. As Burkart suggests: "When our hominin ancestors began to raise their offspring cooperatively, they laid the foundation for both our altruism and our exceptional cognition."

INFORMATION:

Literature:

J. M. Burkart, O. Allon, F. Amici, C. Fichtel, C. Finkenwirth, A. Heschl, J. Huber, K. Isler, Z. K. Kosonen, E. Martins, E. Meulman, R. Richiger, K. Rueth, B. Spillmann, S. Wiesendanger & C. P. van Schaik (2014). The evolutionary origin of human hyper-cooperation. Nature Communications 5:4747 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5747.

Test set-up for the altruism study

A treat is placed on a moving board outside the cage and out of the animal's reach. With the aid of a handle, an animal can pull the board closer and bring the food within reach. However, the handle attached to the board is so far from the food that the individual operating it cannot grab the food itself. Moreover, the board instantly rolls back when the handle is released, moving the food out of reach again, which guarantees that only the other members of the group present are able to get at the snack. In this way, the researchers ensure that the animal operating the handle acts purely altruistically.

For the comparative behavior study with children, an analogous test apparatus was constructed, which was enclosed in a Plexiglas box and could be operated from outside by the children.

Contacts:

Dr. Judith Burkart

Anthropological Institute & Museum, University of Zürich

Winterthurerstrasse 190

CH-8057 Zürich

Switzerland

Email: Judith.burkart@aim.uzh.ch

Phone: +41 44 635 54 02/ +41 76 341 95 67

The roots of human altruism

2014-08-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Fighting prostate cancer with a tomato-rich diet

2014-08-27

Men who eat over 10 portions a week of tomatoes have an 18 per cent lower risk of developing prostate cancer, new research suggests.

With 35,000 new cases every year in the UK, and around 10,000 deaths, prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in men worldwide.

Rates are higher in developed countries, which some experts believe is linked to a Westernised diet and lifestyle.

To assess if following dietary and lifestyle recommendations reduces risk of prostate cancer, researchers at the Universities of Bristol, Cambridge and Oxford looked at the diets and lifestyle ...

Leading scientists call for a stop to non-essential use of fluorochemicals

2014-08-27

Fluorochemicals are synthetically produced chemicals, which repel water and oil and are persistent towards aggressive physical and chemical conditions in industrial processing. These characteristics have made the fluorochemicals useful in numerous processes and products, such as coatings for food paper and board.

The problem with fluorochemicals is that they are difficult to break down and accumulate in both humans and the environment. Some fluorochemicals have known correlations with harmful health effects, such as cancer, increased cholesterol and a weaker immune system ...

Penn paleontologists describe a possible dinosaur nest and young 'babysitter'

2014-08-27

Dinosaurs are often depicted as giant, frightening beasts. But every creature is a baby once.

A new examination of a rock slab containing fossils of 24 very young dinosaurs and one older individual is suggestive of a group of hatchlings overseen by a caretaker, according to a new study by University of Pennsylvania researchers.

Penn's Brandon P. Hedrick and Peter Dodson led the work, collaborating with researchers from China's Dalian Museum of Natural History, where the specimen is held. Hedrick is a doctoral student in the School of Arts & Sciences' Department of Earth ...

Potential therapy for incurable Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease

2014-08-27

This news release is available in German.

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A is the most common inherited disease affecting the peripheral nervous system. Researchers from the Department of Neurogenetics at the Max Planck Institute of Experimental Medicine and University Medical Centre Göttingen have discovered that the maturity of Schwann cells is impaired in rats with the disease. These cells enwrap the nerve fibres with an insulating layer known as myelin, which facilitates the rapid transfer of electrical impulses. If Schwann cells cannot mature correctly, ...

Potential therapy for the Sudan strain of Ebola could help contain some future outbreaks

2014-08-27

Ebola is a rare, but deadly disease that exists as five strains, none of which have approved therapies. One of the most lethal strains is the Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV). Although not the strain currently devastating West Africa, SUDV has caused widespread illness, even as recently as 2012. In a new study appearing in the journal ACS Chemical Biology, researchers now report a possible therapy that could someday help treat patients infected with SUDV.

John Dye, Sachdev Sidhu, Jonathan Lai and colleagues explain that about 50-90 percent of ebola patients die after experiencing ...

How to prevent organic food fraud

2014-08-27

A growing number of consumers are willing to pay a premium for fruits, vegetables and other foods labelled "organic", but whether they're getting what the label claims is another matter. Now scientists studying conventional and organic tomatoes are devising a new way to make sure farms are labelling their produce appropriately. Their report, which appears in ACS' Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, could help prevent organic food fraud.

Researchers from the Bavarian Health and Food Safety Authority and the Wuerzburg University note that the demand for organic ...

New study throws into question long-held belief about depression

2014-08-27

New evidence puts into doubt the long-standing belief that a deficiency in serotonin — a chemical messenger in the brain — plays a central role in depression. In the journal ACS Chemical Neuroscience, scientists report that mice lacking the ability to make serotonin in their brains (and thus should have been "depressed" by conventional wisdom) did not show depression-like symptoms.

Donald Kuhn and colleagues at the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center and Wayne State University School of Medicine note that depression poses a major public health problem. More than 350 million ...

Fear, safety and the role of sleep in human PTSD

2014-08-27

The effectiveness of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment may hinge significantly upon sleep quality, report researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System in a paper published today in the Journal of Neuroscience.

"I think these findings help us understand why sleep disturbances and nightmares are such important symptoms in PTSD," said Sean P.A. Drummond, PhD, professor of psychiatry and director of the Behavioral Sleep Medicine Program at the VA San Diego Healthcare System. "Our study ...

Men who are uneducated about their prostate cancer have difficulty making good treatment choices

2014-08-27

They say knowledge is power, and a new UCLA study has shown this is definitely the case when it comes to men making the best decisions about how to treat their prostate cancer.

UCLA researchers found that men who aren't well educated about their disease have a much more difficult time making treatment decisions, called decisional conflict, a challenge that could negatively impact the quality of their care and their long-term outcomes.

The study should serve as a wake-up call for physicians, who can use the findings to target men less likely to know a lot about their ...

In sync and in control?

2014-08-27

In the aftermath of the Aug. 9 shooting of an 18-year-old African American man by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, much of the nation's attention has been focused on how law enforcement's use of military gear might have inflamed tensions.

But what if the simple act of marching in unison — as riot police routinely do — increases the likelihood that law enforcement will use excessive force in policing protests?

That's the suggestion of a new study by a pair of UCLA social scientists.

"We have found that when men are walking in step with other men, they ...