(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- When we want to listen carefully to someone, the first thing we do is stop talking. The second thing we do is stop moving altogether. This strategy helps us hear better by preventing unwanted sounds generated by our own movements.

This interplay between movement and hearing also has a counterpart deep in the brain. Indeed, indirect evidence has long suggested that the brain's motor cortex, which controls movement, somehow influences the auditory cortex, which gives rise to our conscious perception of sound.

A new Duke study, appearing online August 27 in Nature, combines cutting-edge methods in electrophysiology, optogenetics and behavioral analysis to reveal exactly how the motor cortex, seemingly in anticipation of movement, can tweak the volume control in the auditory cortex.

The new lab methods allowed the group to "get beyond a century's worth of very powerful but largely correlative observations, and develop a new, and really a harder, causality-driven view of how the brain works," said the study's senior author Richard Mooney Ph.D., a professor of neurobiology at Duke University School of Medicine, and a member of the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences.

The findings contribute to the basic knowledge of how communication between the brain's motor and auditory cortexes might affect hearing during speech or musical performance. Disruptions to the same circuitry may give rise to auditory hallucinations in people with schizophrenia.

In 2013, researchers led by Mooney first characterized the connections between motor and auditory areas in mouse brain slices as well as in anesthetized mice. The new study answers the critical question of how those connections operate in an awake, moving mouse.

"This is a major step forward in that we've now interrogated the system in an animal that's freely behaving," said David Schneider, a postdoctoral associate in Mooney's lab.

Mooney suspects that the motor cortex learns how to mute responses in the auditory cortex to sounds that are expected to arise from one's own movements while heightening sensitivity to other, unexpected sounds. The group is testing this idea.

"Our first step will be to start making more realistic situations where the animal needs to ignore the sounds that its movements are making in order to detect things that are happening in the world," Schneider said.

In the latest study, the team recorded electrical activity of individual neurons in the brain's auditory cortex. Whenever the mice moved -- walking, grooming, or making high-pitched squeaks -- neurons in their auditory cortex were dampened in response to tones played to the animals, compared to when they were at rest.

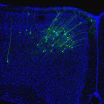

To find out whether movement was directly influencing the auditory cortex, researchers conducted a series of experiments in awake animals using optogenetics, a powerful method that uses light to control the activity of select populations of neurons that have been genetically sensitized to light. Like the game of telephone, sounds that enter the ear pass through six or more relays in the brain before reaching the auditory cortex.

"Optogenetics can be used to activate a specific relay in the network, in this case the penultimate node that relays signals to the auditory cortex," Mooney said.

About half of the suppression during movement was found to originate within the auditory cortex itself. "That says a lot of modulation is going on in the auditory cortex, and not just at earlier relays in the auditory system" Mooney said.

More specifically, the team found that movement stimulates inhibitory neurons that in turn suppress the response of the auditory cortex to tones.

The researchers then wondered what turns on the inhibitory neurons. The suspects were many. "The auditory cortex is like this giant switching station where all these different inputs come through and say, 'Okay, I want to have access to these interneurons,' " Mooney said. "The question we wanted to answer is who gets access to them during movement?"

The team knew from previous experiments that neuronal projections from the secondary motor cortex (M2) modulate the auditory cortex. But to isolate M2's relative contribution -- something not possible with traditional electrophysiology -- the researchers again used optogenetics, this time to switch on and off the M2's inputs to the inhibitory neurons.

Turning on M2 inputs reproduced a sense of movement in the auditory cortex, even in mice that were resting, the group found. "We were sending a 'Hey I'm moving' signal to the auditory cortex," Schneider said. Then the effect of playing a tone on the auditory cortex was much the same as if the animal had actually been moving -- a result that confirmed the importance of M2 in modulating the auditory cortex. On the other hand, turning off M2 simulated rest in the auditory cortex, even when the animals were still moving.

"I couldn't contain my excitement when we first saw that result," said Anders Nelson, a neurobiology graduate student in Mooney's group.

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation, the Holland-Trice Graduate Fellowship in Brain Sciences, and the National Institutes of Health (NS079929).

CITATION: " A synaptic and circuit basis for corollary discharge in the auditory cortex," David M. Schneider, Anders Nelson, Richard Mooney. Nature, August 27, 2014. DOI: 10.1038/nature13724

Stop and listen: Study shows how movement affects hearing

Brain's motor areas can directly turn down hearing

2014-08-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NASA sees massive Marie close enough to affect southern California coast

2014-08-27

Two NASA satellites captured visible and infrared pictures that show the massive size of Hurricane Marie. Marie is so large that it is bringing rough surf to the southern coast of California while almost nine hundred miles west of Baja California.

On August 26 at 19:05 UTC (3:05 p.m. EDT) NASA's Terra satellite captured a visible image of Hurricane Marie drawing in the small remnants of Karina. Marie is over 400 miles in diameter, about the distance from Washington, D.C. to Boston, Massachusetts. Hurricane force winds extend outward up to 60 miles (95 km) from the center ...

Scripps Research Institute scientists link alcohol-dependence gene to neurotransmitter

2014-08-27

LA JOLLA, CA – August 27, 2014 – Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have solved the mystery of why a specific signaling pathway can be associated with alcohol dependence.

This signaling pathway is regulated by a gene, called neurofibromatosis type 1 (Nf1), which TSRI scientists found is linked with excessive drinking in mice. The new research shows Nf1 regulates gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), a neurotransmitter that lowers anxiety and increases feelings of relaxation.

"This novel and seminal study provides insights into the cellular mechanisms of ...

Expression of privilege in vaccine refusal

2014-08-27

DENVER (August 27, 2014) – Not all students returning to school this month will be up to date on their vaccinations. A new study conducted by Jennifer Reich, a researcher at the University of Colorado Denver, shows that the reasons why children may not be fully vaccinated depends on the class privilege of their mothers.

According to the National Network for Immunization Information, three children per 1000 in the U.S. have never received any vaccines, with almost half of all children receiving vaccines later than recommended. The number of unvaccinated children has led ...

Dosage of HIV drug may be ineffective for half of African-Americans

2014-08-27

Many African-Americans may not be getting effective doses of the HIV drug maraviroc, a new study from Johns Hopkins suggests. The initial dosing studies, completed before the drug was licensed in 2007, included mostly European-Americans, who generally lack a protein that is key to removing maraviroc from the body. The current study shows that people with maximum levels of the protein — including nearly half of African-Americans — end up with less maraviroc in their bodies compared to those who lack the protein even when given the same dose. A simple genetic test for the ...

Scientists plug into a learning brain

2014-08-27

Learning is easier when it only requires nerve cells to rearrange existing patterns of activity than when the nerve cells have to generate new patterns, a study of monkeys has found. The scientists explored the brain's capacity to learn through recordings of electrical activity of brain cell networks. The study was partly funded by the National Institutes of Health.

"We looked into the brain and may have seen why it's so hard to think outside the box," said Aaron Batista, Ph.D., an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh and a senior author of the study published ...

Pitt and Carnegie Mellon engineers discover why learning can be difficult

2014-08-27

PITTSBURGH—Learning a new skill is easier when it is related to ability that we already possess. For example, a trained pianist might learn a new melody more easily than learning how to hit a tennis serve.

Neural engineers from the Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition (CNBC)—a joint program between the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University—have discovered a fundamental constraint in the brain that may explain why this happens. Published as the cover story in the Aug. 28, 2014, issue of Nature, they found for the first time that there are constraints ...

Kessler Foundation scientists study impact of cultural diversity in brain injury research

2014-08-27

West Orange, NJ. August 27, 2014. Kessler Foundation scientists examined the implications for cultural diversity and cultural competence in brain injury research and rehabilitation. The article by Anthony Lequerica, PhD, and Denise Krch, PhD: Issues of cultural diversity in acquired brain injury (ABI) rehabilitation (doi:10.3233/NRE-141079) was published by Neurorehabilitation. Drs. Lequerica and Krch are research scientists in Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Research at Kessler Foundation and co-investigators for the Northern New Jersey TBI Model System.

Cultural sensitivity ...

New smartphone app can detect newborn jaundice in minutes

2014-08-27

Newborn jaundice: It's one of the last things a parent wants to deal with, but it's unfortunately a common condition in babies less than a week old.

Skin that turns yellow can be a sure sign that a newborn is jaundiced and isn't adequately eliminating the chemical bilirubin. But that discoloration is sometimes hard to see, and severe jaundice left untreated can harm a baby.

University of Washington engineers and physicians have developed a smartphone application that checks for jaundice in newborns and can deliver results to parents and pediatricians within minutes. ...

Parents, listen next time your baby babbles

2014-08-27

Pay attention, mom and dad, especially when your infant looks at you and babbles.

Parents may not understand a baby's prattling, but by listening and responding, they let their infants know they can communicate which leads to children forming complex sounds and using language more quickly.

That's according to a new study by the University of Iowa and Indiana University that found how parents respond to their children's babbling can actually shape the way infants communicate and use vocalizations.

The findings challenge the belief that human communication is innate ...

Lifetime of fitness: A fountain of youth for bone and joint health?

2014-08-27

ROSEMONT, Ill.—Being physically active may significantly improve musculoskeletal and overall health, and minimize or delay the effects of aging, according to a review of the latest research on senior athletes (ages 65 and up) appearing in the September issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (JAAOS).

It long has been assumed that aging causes an inevitable deterioration of the body and its ability to function, as well as increased rates of related injuries such as sprains, strains and fractures; diseases, such as obesity and diabetes; and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

Combining AI with OCT shows potential for detecting lipid-rich plaques in coronary arteries

SeaCast revolutionizes Mediterranean Sea forecasting with AI-powered speed and accuracy

JMIR Publications’ JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology invites submissions on Bridging Data, AI, and Innovation to Transform Health

Honey bees navigate more precisely than previously thought

Air pollution may directly contribute to Alzheimer’s disease

Study finds early imaging after pediatric UTIs may do more harm than good

UC San Diego Health joins national research for maternal-fetal care

New biomarker predicts chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer

Treatment algorithms featured in Brain Trauma Foundation’s update of guidelines for care of patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury

Over 40% of musicians experience tinnitus; hearing loss and hyperacusis also significantly elevated

Artificial intelligence predicts colorectal cancer risk in ulcerative colitis patients

Mayo Clinic installs first magnetic nanoparticle hyperthermia system for cancer research in the US

Calibr-Skaggs and Kainomyx launch collaboration to pioneer novel malaria treatments

JAX-NYSCF Collaborative and GSK announce collaboration to advance translational models for neurodegenerative disease research

Classifying pediatric brain tumors by liquid biopsy using artificial intelligence

Insilico Medicine initiates AI driven collaboration with leading global cancer center to identify novel targets for gastroesophageal cancers

Immunotherapy plus chemotherapy before surgery shows promise for pancreatic cancer

A “smart fluid” you can reconfigure with temperature

New research suggests myopia is driven by how we use our eyes indoors

Scientists develop first-of-its-kind antibody to block Epstein Barr virus

[Press-News.org] Stop and listen: Study shows how movement affects hearingBrain's motor areas can directly turn down hearing