(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- Scientists have identified the developmental on-off switch for Streptomyces, a group of soil microbes that produce more than two-thirds of the world's naturally derived antibiotic medicines.

Their hope now would be to see whether it is possible to manipulate this switch to make nature's antibiotic factory more efficient.

The study, appearing August 28 in Cell, found that a unique interaction between a small molecule called cyclic-di-GMP and a larger protein called BldD ultimately controls whether a bacterium spends its time in a vegetative state or gets busy making antibiotics.

Researchers found that the small molecule assembles into a sort of molecular glue, connecting two copies of BldD as a cohesive unit that can regulate development in the Gram-positive bacteria Streptomyces.

"For decades, scientists have been wondering what flips the developmental switch in Streptomyces to turn off normal growth and to begin the unusual process of multicellular differentiation in which it generates antibiotics," said Maria A. Schumacher, Ph.D., an associate professor of biochemistry at the Duke University School of Medicine. "Now we not only know that cyclic-di-GMP is responsible, but we also know exactly how it interacts with the protein BldD to activate its function."

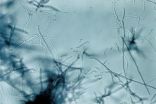

Streptomyces has a complex life cycle with two distinct phases: the dividing, vegetative phase and a distinct phase in which the bacteria form a network of thread-like filaments to chew up organic debris and churn out antibiotics and other metabolites. At the end of this second phase, the bacteria form filamentous branches that extend into the air to create spiraling towers of spores.

In 1998 researchers discovered a gene that kept cultured Streptomyces bacteria from creating these spiraling towers of fuzz on their surface. They found that this gene, which they named BldD to reflect this "bald" appearance, also affected the production of antibiotics.

Subsequent studies have shown that BldD is a special protein called a transcription factor, a type of master regulator that binds DNA and turns on or off more than a hundred genes to control biological processes like sporulation. But in more than a decade of investigation, no one had been able to identify the brains behind the operation, the molecule that ultimately controls this master regulator in Streptomyces.

Then scientists at the John Innes Centre in the United Kingdom -- where much of the research on Streptomyces began -- discovered that the small molecule cyclic-di-GMP is generated by several transcription factors regulated by BldD. The researchers did a quick test to see if this small molecule would itself bind BldD, and were amazed to find that it did. They contacted longtime collaborators Schumacher and Richard G. Brennan Ph.D. at Duke to see if they could take a closer look at this important interaction.

The Duke team used a tool known as x-ray crystallography to create an atomic-level three-dimensional structure of the BldD-(cyclic-di-GMP) complex.

BldD normally exists as a single molecule or monomer, but when it is time to bind DNA and suppress sporulation, it teams up with another copy of itself to do the job. The 3D structure built by the researchers revealed that these two copies of BldD never physically touch, and instead are stuck together by four copies of cyclic-di-GMP.

"We have looked through the protein databank and scoured our memories, but this finding appears to be unique," said Brennan, who is a professor and chair of biochemistry at Duke University School of Medicine. "We have never seen a type of structure before where two monomers become a functional dimer, with no direct interaction between them except a kind of small-molecule glue."

To confirm their findings, Schumacher determined several crystal structures from different flavors of bacteria (S. venezuelae and S. coelicolor) and came up with the same unusual result every time.

Now that the researchers know how cyclic-di-GMP and BldD can become glued together to turn off sporulation and turn on antibiotic production, they would like to know how the complex can become unglued again to flip the switch the other way.

The research was supported by a Long Term EMBO Fellowship (ALTF 693-2012), a Leopoldina Postdoctoral Fellowship, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/H006125/1), the MET Institute Strategic Programme, and the Duke University School of Medicine.

INFORMATION:

CITATION: "Tetrameric c-di-GMP mediates effective transcription factor dimerization to control Streptomyces development," Natalia Tschowri, Maria A. Schumacher, Susan Schlimpert, Nagababu Chinnam, Kim C. Findlay, Richard G. Brennan, and Mark J.

Buttner. Cell, August 28, 2014.

Small molecule acts as on-off switch for nature's antibiotic factory

Tells Streptomyces to either veg out or get busy

2014-08-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Second-hand e-cig smoke compared to regular cigarette smoke

2014-08-28

E-cigarettes are healthier for your neighbors than traditional cigarettes, but still release toxins into the air, according to a new study from USC.

Scientists studying secondhand smoke from e-cigarettes discovered an overall 10-fold decrease in exposure to harmful particles, with close-to-zero exposure to organic carcinogens. However, levels of exposure to some harmful metals in second-hand e-cigarette smoke were found to be significantly higher.

While tobacco smoke contains high levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons – cancer-causing organic compounds – the level ...

Healthy Moms program helps women who are obese limit weight gain during pregnancy

2014-08-28

PORTLAND, Ore., August 28, 2014 — A new study finds that women who are obese can limit their weight gain during pregnancy using conventional weight loss techniques including attending weekly group support meetings, seeking advice about nutrition and diet, and keeping food and exercise journals.

Results of the Healthy Moms study, published in Obesity, also show that obese women who limit their weight gain during pregnancy are less likely to have large-for-gestational age babies which can complicate delivery and increase the baby's risk of becoming obese later in life.

"Most ...

University of Montana cicada study discovers 2 genomes that function as 1

2014-08-28

MISSOULA, Mont. – Two is company, three is a crowd. But in the case of the cicada, that's a good thing.

Until a recent discovery by a University of Montana research lab, it was thought that cicadas had a symbiotic relationship with two important bacteria that live within the cells of its body. Since the insect eats a simple diet consisting solely of plant sap, it relies on these bacteria to produce the nutrients it needs for survival.

In exchange, those two bacteria, Hodgkinia and Sulcia, live comfortably inside the cicada. Since all three divvy up the nutritional roles, ...

Non-adaptive evolution in a cicada's gut

2014-08-28

Organisms in a symbiotic relationship will often shed genes as they come to rely on the other organism for crucial functions. But now researchers have uncovered an unusual event in which a bacterium that lives in a type of cicada split into two species, doubling the number of organisms required for the symbiosis to survive.

Cicadas of the genus Tettigades feed only on sap they suck out of plants. To create some of the essential amino acids they rely on two bacterial helpers — Candidatus Hodgkinia cicadicola and Candidatus Sulcia muelleri — with which they have lived in ...

How studying damage to the prefrontal lobe has helped unlock the brain's mysteries

2014-08-28

Until the last few decades, the frontal lobes of the brain were shrouded in mystery and erroneously thought of as nonessential for normal function—hence the frequent use of lobotomies in the early 20th century to treat psychiatric disorders. Now a review publishing August 28 in the Cell Press journal Neuron highlights groundbreaking studies of patients with brain damage that reveal how distinct areas of the frontal lobes are critical for a person's ability to learn, multitask, control their emotions, socialize, and make real-life decisions. The findings have helped experts ...

Circulating tumor cell clusters more likely to cause metastasis than single cells

2014-08-28

Circulating tumor cell (CTC) clusters – clumps of from 2 to 50 tumor cells that break off a primary tumor and are carried through the bloodstream – appear to be much more likely to cause metastasis than are single CTCs, according to a study from investigators at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Cancer Center. Their report in the August 28 issue of Cell also suggests that a cell adhesion protein binding CTC clusters together is a potential therapeutic target.

"While CTCs are considered to be precursors of metastasis, the significance of CTC clusters, which are ...

NYU researchers ID process producing neuronal diversity in fruit flies' visual system

2014-08-28

New York University biologists have identified a mechanism that helps explain how the diversity of neurons that make up the visual system is generated.

"Our research uncovers a process that dictates both timing and cell survival in order to engender the heterogeneity of neurons used for vision," explains NYU Biology Professor Claude Desplan, the study's senior author.

The study's other co-authors were: Claire Bertet, Xin Li, Ted Erclik, Matthieu Cavey, and Brent Wells—all postdoctoral fellows at NYU.

Their work, which appears in the latest issue of the journal Cell, ...

Zombie bacteria are nothing to be afraid of

2014-08-28

VIDEO:

Heidi Arjes of Washington University in St. Louis explains how the failsafes in the bacterial cell cycle work. A bacterium that fails to pass either failsafe enters a zombified state...

Click here for more information.

A cell is not a soap bubble that can simply pinch in two to reproduce. The ability to faithfully copy genetic material and distribute it equally to daughter cells is fundamental to all forms of life. Even seemingly simple single-celled organisms must have ...

Research shows how premalignant cells can sense oncogenesis and halt growth

2014-08-28

Cold Spring Harbor, NY -- What happens inside cells when they detect the activation of a cancer-inducing gene? Sometimes, cells are able to signal internally to stop the cell cycle. Such cells are able to enter, at least for a time, a protective non-growth state.

Since the 1980s, scientists have known that mutations in a human gene called RAS are capable of setting cells on a path to cancer. Today, a team at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) publishes experiments showing how cells can respond to an activated RAS gene by entering a quiescent state, called senescence.

CSHL ...

Computer games give a boost to English

2014-08-28

If you want to make a mark in the world of computer games you had better have a good English vocabulary. It has now also been scientifically proven that someone who is good at computer games has a larger English vocabulary. This is revealed by a study at the University of Gothenburg and Karlstad University, Sweden.

The study confirms what many parents and teachers already suspected: young people who play a lot of interactive English computer games gain an advantage in terms of their English vocabulary compared with those who do not play or only play a little.

The study ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Antarctica sits above Earth’s strongest “gravity hole.” Now we know how it got that way

Haircare products made with botanicals protects strands, adds shine

Enhanced pulmonary nodule detection and classification using artificial intelligence on LIDC-IDRI data

Using NBA, study finds that pay differences among top performers can erode cooperation

Korea University, Stanford University, and IESGA launch Water Sustainability Index to combat ESG greenwashing

Molecular glue discovery: large scale instead of lucky strike

Insulin resistance predictor highlights cancer connection

Explaining next-generation solar cells

Slippery ions create a smoother path to blue energy

Magnetic resonance imaging opens the door to better treatments for underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonisms

National poll finds gaps in community preparedness for teen cardiac emergencies

One strategy to block both drug-resistant bacteria and influenza: new broad-spectrum infection prevention approach validated

Survey: 3 in 4 skip physical therapy homework, stunting progress

College students who spend hours on social media are more likely to be lonely – national US study

Evidence behind intermittent fasting for weight loss fails to match hype

How AI tools like DeepSeek are transforming emotional and mental health care of Chinese youth

Study finds link between sugary drinks and anxiety in young people

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

[Press-News.org] Small molecule acts as on-off switch for nature's antibiotic factoryTells Streptomyces to either veg out or get busy