(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

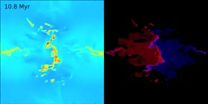

This computer simulation shows the collision of two streams of interstellar gas, leading to gravitational collapse of the gas and the formation of a star cluster at the center. The...

Click here for more information.

The chemical uniformity of stars in the same cluster is the result of turbulent mixing in the clouds of gas where star formation occurs, according to a study by astrophysicists at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Their results, published August 31 in Nature, show that even stars that don't stay together in a cluster will share a chemical fingerprint with their siblings which can be used to trace them to the same birthplace.

"We can see that stars that are part of the same star cluster today are chemically identical, but we had no good reason to think that this would also be true of stars that were born together and then dispersed immediately rather than forming a long-lived cluster," said Mark Krumholz, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz.

Our sun and its siblings, for example, probably went their own ways within a few million years after they were born, Krumholz said. The new study suggests that astronomers could potentially find the sun's long-lost siblings even if they are now on the opposite side of the galaxy.

Krumholz and UC Santa Cruz graduate student Yi Feng used supercomputers to simulate two streams of interstellar gas coming together to form a cloud that, over the course of a few million years, collapses under its own gravity to make a cluster of stars. Studies of interstellar gas show much greater variation in chemical abundances than is seen among stars within the same open star cluster. To represent this variation, the researchers added "tracer dyes" to the two gas streams in the simulations. The results showed extreme turbulence as the two streams came together, and this turbulence effectively mixed together the tracer dyes.

"We put red dye in one stream and blue dye in the other, and by the time the cloud started to collapse and form stars, everything was purple. The resulting stars were purple as well," Krumholz said. "This explains why stars that are born together wind up having the same abundances: as the cloud that forms them is assembled, it gets thoroughly mixed. This was actually a bit of a surprise. I didn't expect the turbulence to be as violent as it was, so I didn't expect the mixing to be as rapid or efficient. I thought we'd get some blue stars and some red stars, instead of getting all purple stars."

The simulations also showed that the mixing happens very fast, before much of the gas has turned into stars. This is encouraging for the prospects of finding the sun's siblings, because the distinguishing characteristic of stellar families that don't stay together is that they probably disperse before much of their parent cloud has been converted to stars. If the mixing didn't happen quickly enough, then the chemical uniformity of star clusters would be the exception rather than the rule. Instead, the simulations indicate that even clouds that don't turn much of their gas into stars produce stars with nearly identical chemical signatures.

"The idea of finding the siblings of the sun through chemical tagging is not new, but no one had any idea if it would work," Krumholz said. "The underlying problem was that we didn't really know why stars in clusters are chemically homogeneous, and so we couldn't make any sensible predictions about what would happen in the environment where the Sun formed, which must have been quite different from the environments that give rise to long-lived star clusters. This study puts the idea on much firmer footing and will hopefully spur greater efforts toward making use of this technique."

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation and NASA.

Mixing in star-forming clouds explains why sibling stars look alike

2014-08-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Antarctic sea-level rising faster than global rate

2014-08-31

A new study of satellite data from the last 19 years reveals that fresh water from melting glaciers has caused the sea-level around the coast of Antarctica to rise by 2cm more than the global average of 6cm.

Researchers at the University of Southampton detected the rapid rise in sea-level by studying satellite scans of a region that spans more than a million square kilometres.

The melting of the Antarctic ice sheet and the thinning of floating ice shelves has contributed an excess of around 350 gigatonnes of freshwater to the surrounding ocean. This has led to a reduction ...

Changing global diets is vital to reducing climate change

2014-08-31

A new study, published today in Nature Climate Change, suggests that – if current trends continue – food production alone will reach, if not exceed, the global targets for total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2050.

The study's authors say we should all think carefully about the food we choose and its environmental impact. A shift to healthier diets across the world is just one of a number of actions that need to be taken to avoid dangerous climate change and ensure there is enough food for all.

As populations rise and global tastes shift towards meat-heavy Western ...

A new way to diagnose malaria

2014-08-31

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Over the past several decades, malaria diagnosis has changed very little. After taking a blood sample from a patient, a technician smears the blood across a glass slide, stains it with a special dye, and looks under a microscope for the Plasmodium parasite, which causes the disease. This approach gives an accurate count of how many parasites are in the blood — an important measure of disease severity — but is not ideal because there is potential for human error.

A research team from the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART) has now ...

Memory and Alzheimer's: Towards a better comprehension of the dynamic mechanisms

2014-08-31

This news release is available in French. Montréal, August 31, 2014 – A study just published in the prestigious Nature Neuroscience journal by, Sylvain Williams, PhD, and his team, of the Research Centre of the Douglas Mental Health University Institute and McGill University, opens the door towards better understanding of the neural circuitry and dynamic mechanisms controlling memory as well of the role of an essential element of the hippocampus – a sub-region named the subiculum.

In 2009, they developed a unique approach – namely, the in vitro preparation of a hippocampal ...

Renal denervation reduces recurrent AF after ablation

2014-08-31

Barcelona, Spain – Sunday 31 August 2014: Renal denervation reduces recurrent atrial fibrillation (AF) when performed with pulmonary vein isolation ablation in patients with AF and hypertension, according to research presented at ESC Congress today by Dr Alexander Romanov from the Russian Federation.

Dr Romanov said: "The prevalence of AF ranges from 1.5 to 2% in developed countries. This arrhythmia is associated with increased mortality, a five-fold risk of stroke and a 3-fold incidence of congestive heart failure. The vast majority of patients with AF also have arterial ...

Energy drinks cause heart problems

2014-08-31

Barcelona, Spain – Sunday 31 August 2014: Energy drinks can cause heart problems according to research presented at ESC Congress 2014 today by Professor Milou-Daniel Drici from France.

Professor Drici said: "So-called 'energy drinks' are popular in dance clubs and during physical exercise, with people sometimes consuming a number of drinks one after the other. This situation can lead to a number of adverse conditions including angina, cardiac arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat) and even sudden death."

He added: "Around 96% of these drinks contain caffeine, with a typical ...

Antihypertensive therapy reduces CV events, strokes and mortality in older adults

2014-08-31

Barcelona, Spain – Sunday 31 August 2014: Antihypertensive therapy reduces the risk of cardiovascular (CV) events, strokes and mortality in hypertensive older adults, according to research presented at ESC Congress 2014 today by Dr Maciej Ostrowski from Poland. The findings suggest that antihypertensive drugs should be considered in all patients over 65 years of age with hypertension.

Dr Ostrowski said: "Over the past few decades, a number of randomised trials and meta‑analyses have supported the benefits of antihypertensive medication in reducing the incidence ...

Resistant hypertension increases stroke risk by 35 percent in women and 20 percent in elderly Taiwanese

2014-08-31

Barcelona, Spain – Sunday 31 August 2014: Resistant hypertension increases the risk of stroke by 35% in women and 20% in elderly Taiwanese patients, according to research presented at ESC Congress today by Dr Kuo-Yang Wang from Taiwan. The findings suggest that gender and age should be added to the risk stratification of resistant hypertension to enable more appropriate treatment decisions.

Dr Wang said: "Hypertension is one of the most important risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Patients with hypertension that does not respond to conventional drug treatments, ...

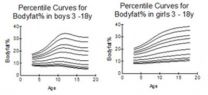

Obese youths have a nearly 6 fold risk of hypertension

2014-08-31

Barcelona, Spain – Sunday 31 August 2014: Obese youths have a nearly six fold risk of hypertension, according to research in more than

22 000 young people from the PEP Family Heart Study presented at ESC Congress today by Professor Peter Schwandt from Germany.

Professor Schwandt said: "The prevalence of hypertension and obesity in children and adolescents is continuing to rise in most high and middle-income countries. Because adiposity is considered a driving force for cardiovascular disease, we examined whether elevated blood pressure was associated with body fat distribution ...

Inhibiting inflammatory enzyme after heart attack does not reduce risk of subsequent event

2014-08-31

In patients who experienced an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) event (such as heart attack or unstable angina), use of the drug darapladib to inhibit the enzyme lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (believed to play a role in the development of atherosclerosis) did not reduce the risk of recurrent major coronary events, according to a study published by JAMA. The study is being released early online to coincide with its presentation at the European Society of Cardiology Congress.

A number of epidemiologic studies have shown that higher circulating levels of lipoprotein-associated ...