(Press-News.org) Chemical reactions drive the mechanisms of life as well as a million other natural processes on earth. These reactions occur at a wide spectrum of temperatures, from those prevailing at the chilly polar icecaps to those at work churning near the earth's core. At nanokelvin temperatures, by contrast, nothing was supposed to happen. Chemistry was expected to freeze up. Experiments and theoretical work have now show that this is not true. Even at conditions close to absolute zero atoms can interact and manage to form chemical bonds.

Within this science of ultracold chemistry, there is a sub-field that deals with "Efimov states," named for Russian physicist Vitaly Efimov. In 1970 he predicted that under some conditions all two-particle bound states would be unstable while (paradoxically) some three-particle states could exist. Such states were eventually seen experimentally in 2006, among cesium atoms (1).

Two scientists at the Joint Quantum Institute have now formulated a universal theory to describe the properties of these Efimov states, a theory that, for the first time, does not need extra adjustable unknown parameters . This should allow physicists to predict the rates of chemical processes involving three atoms---or even more---using only a knowledge of the interaction forces at work.

The JQI authors, Yujun Wang and Paul Julienne, publish their results in the journal Nature Physics (2).

PICO-ELECTRON VOLTS

Efimov states are fragile. They depend for their existence on quantum effects and on the subtle interplay of two phenomena: Feshbach resonance and van der Waal forces. Quantum effects are necessarily at work at ultracold temperatures in the nano-kelvin regime. Here atoms should be viewed not as hard balls, typically a few tenths of nanometers across, but as wave packets, blobs extending over hundreds of nm.

It is common, when talking about colliding particles, to see them as cars speeding toward each other, perhaps meeting head on or glancing off at a relative angle. It is more unusual to visualize the collision if the "particles" are so large as to overlap each other at relatively great distances. More strange still if three such particles are involved in an interaction whose result will be a loosely-bound confederation.

In the study of Efimov states, the primary force at work among the atoms is the van der Waals force, named for Dutch physicist Johannes Diderik van der Waals. This long-range force among atoms or molecules arises from the temporary appearance of electric dipole moments in the particles. Even for a neutral atom, a momentary imbalance of charge---more of the atomic electrons' negative charge might appear to the left, say, leaving a positive preponderance on the right---will constitute an electric dipole, which in turn can attract an atom with a complementary dipole orientation. This induced-dipole force varies at the inverse sixth power of the distance between the two particles.

Another way of controlling inter-particle collisions at ultracold temperatures is to turn on an external magnetic field. For certain ranges of field strength, two particles can be coaxed to form semi-stable objects called Feshbach resonances, named for US physicist Herman Feshbach. Feshbach resonances are commonly used in cold-physics to control interactions, and this is especially true in the study of Efimov states.

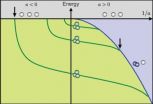

Often Feshbach resonances are described in terms of a parameter, a, called the scattering length, denoting the effective distance over which the interaction takes place If a is positive and large (much larger than the nominal range of the force between the atoms), weak binding of atoms can happen. If a is negative, a slight attraction of two atoms can occur but not binding. If, however, a is large and three atoms are present, then the Efimov state can appear. Indeed an infinite number of such states can occur.

In general since it allows interactions over large distances, the Feshbach effect is more important than the van der Waals force. But the JQI research has shown how the van der Waals force can be decisive in forming Efimov states, especially when the scattering length is short. Many scientists had believed that making consistent predictions of triplet-forming interactions would be difficult to make. Instead, the Wang-Julienne model successfully incorporates this short-distance regime.

Thus there should be a series of Efimov states, with various binding energies. But unlike atoms, where the quantum energy levels (denoting how much energy is needed to liberate the electron from its atomic binding) are in the electron volt (eV) range, Efimof states are typified by quantum energies of billionths of an eV or less.

THE NEW JQI THEORY

Wang and Julienne build their theory of 3-body van der Waals physics around the Schrödinger equation, the equation introduced by Erwin Schrödinger in the 1920s to treat particles as waves. Only here it is three particles---viewed as three sets of waves, or rather as a complex of waves representing the three particles---carefully studied in pairwise fashion to simulate an effective composite force field in which the three particles operate.

The result is a theoretical tool that can predict the important Efimov properties, namely the energies of the Efimov states, the widths of those states (essentially the fuzziness of our knowledge of the precise energy value), and the rates at which the three-particle states will form inside a gas of ultracold atoms.

"Our theory works for a full range of scattering lengths," said Yujun Wang describing the JQI work, "whereas the previous theories could only apply to large scattering lengths. We don't need adjustable parameters. The only inputs in our theory are the known two-body Feshbach parameters and our calculations using the Schrodinger equation. So our theory does not rely on any of the unknown three-body inputs that have been used in previous theories to fit the experimental data. In these two aspects our theory is more comprehensive and powerful. We can make quantitative predictions without relying on the unknowns, so that our results can be directly compared to experiments."

INFORMATION:

1. Previous press release on Efimov states: http://jqi.umd.edu/news/278-hints-of-universal-behavior-seen-in-exotic-3-atom-states.html

2. "Universal van der Waals Physics for Three Cold Atoms near Feshbach Resonances," Yujun Wang_ and Paul S. Julienne, Nature Physics, September 2014, published online 24 August 2014: http://www.nature.com/nphys/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nphys3071.html

Paul Julienne, psj@umd.edu Yujun Wang, yujunw@phys.ksu.edu

Press contact at JQI: Phillip F. Schewe, pschewe@umd.edu, 301-405-0989. http://jqi.umd.edu/

Cool calculations for cold atoms

New theory of universal three-body encounters

2014-09-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Enzyme controlling metastasis of breast cancer identified

2014-09-02

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have identified an enzyme that controls the spread of breast cancer. The findings, reported in the current issue of PNAS, offer hope for the leading cause of breast cancer mortality worldwide. An estimated 40,000 women in America will die of breast cancer in 2014, according to the American Cancer Society.

"The take-home message of the study is that we have found a way to target breast cancer metastasis through a pathway regulated by an enzyme," said lead author Xuefeng Wu, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher ...

Study links sex hormone levels in the blood to risk of sudden cardiac arrest

2014-09-02

LOS ANGELES (Sept. 2, 2014) – Measuring the levels of sex hormones in patients' blood may identify patients likely to suffer a sudden cardiac arrest, a heart rhythm disorder that is fatal in 95 percent of patients.

A new study, published online by the peer-reviewed journal Heart Rhythm, shows that lower levels of testosterone, the predominant male sex hormone, were found in men who had a sudden cardiac arrest. Higher levels of estradiol, the major female sex hormone, were strongly associated with greater chances of having a sudden cardiac arrest in both men and women. ...

UO-Berkeley Lab unveil new nano-sized synthetic scaffolding technique

2014-09-02

EUGENE, Ore. -- Scientists, including University of Oregon chemist Geraldine Richmond, have tapped oil and water to create scaffolds of self-assembling, synthetic proteins called peptoid nanosheets that mimic complex biological mechanisms and processes.

The accomplishment -- detailed this week in a paper placed online ahead of print by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences -- is expected to fuel an alternative design of the two-dimensional peptoid nanosheets that can be used in a broad range of applications. Among them could be improved chemical sensors ...

Microphysiological systems will revolutionize experimental biology and medicine

2014-09-02

The Annual Thematic issue of Experimental Biology and Medicine that appears in September 2014 is devoted to "The biology and medicine of microphysiological systems" and describes the work of scientists participating in the Microphysiological Systems Program directed by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and funded in part by the NIH Common Fund. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are collaborating with the NIH in the program. Fourteen of ...

An uphill climb for mountain species?

2014-09-02

A recently published paper provides a history of scientific research on mountain ecosystems, looks at the issues threatening wildlife in these systems, and sets an agenda for biodiversity conservation throughout the world's mountain regions.

The paper, "Mountain gloom and mountain glory revisited: A survey of conservation, connectivity, and climate change in mountain regions," appears online in the Journal of Mountain Ecology. Authors are Charles C. Chester of Tufts University, Jodi A. Hilty of the Wildlife Conservation Society, and Lawrence S. Hamilton of World Commission ...

Sabotage as therapy: Aiming lupus antibodies at vulnerable cancer cells

2014-09-02

New Haven, Conn. — Yale Cancer Center researchers may have discovered a new way of harnessing lupus antibodies to sabotage cancer cells made vulnerable by deficient DNA repair.

The findings were published recently in Nature's journal Scientific Reports.

The study, led by James E. Hansen, M.D., assistant professor of therapeutic radiology at Yale School of Medicine, found that cancer cells with deficient DNA repair mechanisms (or the inability to repair their own genetic damage) were significantly more vulnerable to attack by lupus antibodies.

"Patients with lupus ...

Seatbelt laws encourage obese drivers to buckle up

2014-09-02

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Obesity is associated with many health risks, including heart disease and diabetes, but University of Illinois researchers have found a possible way to mitigate one often-overlooked risk: not buckling up in the car.

A new study led by Sheldon H. Jacobson, a professor of computer science and of mathematics, found that increasing the obesity rates are associated with a decrease in seatbelt usage. However, these effects can be mitigated when seatbelt laws are in effect.

"Primary seatbelt laws lead to increased use of seatbelts," Jacobson said. "On the ...

Melatonin does not reduce delirium in elderly patients having acute hip surgery

2014-09-02

Melatonin supplements do not appear to lessen delirium in elderly people undergoing surgery for hip fractures, indicates a new trial published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal)

Many older patients in hospital experience delirium, with disturbances in their sleep–wake cycle. Antipsychotic medications used to reduce symptoms have serious adverse effects, leading the US Food and Drug Administration to warn against their use. Benzodiazepines are also used, although they are known to cause or aggravate delirium. A lack of melatonin may be one factor underlying ...

Changing microbial dynamics in the wake of the Macondo blowout

2014-09-02

In an article in the September issue of BioScience, Samantha Joye and colleagues describe Gulf of Mexico microbial communities in the aftermath of the 2010 Macondo blowout. The authors describe revealing population-level responses of hydrocarbon-degrading microbes to the unprecedented deepwater oil plume.

The spill provided a unique opportunity to study the responses of indigenous microbial communities to a substantial injection of hydrocarbons. Surveys of genetic identifiers within cells known as ribosomal RNA and analyses relying on modern techniques including metagenomics, ...

Humiliation tops list of mistreatment toward med students

2014-09-02

Each year thousands of students enroll in medical schools across the country. But just how many feel they've been disrespected, publicly humiliated, ridiculed or even harassed by their superiors at some point during their medical education?

Recently, researchers at Michigan State University were the first to analyze 12 years worth of national survey data from the Association of American Medical Colleges, or AAMC, questioning graduating students about their medical school experience during the clinical portion of their education.

They found that up to 20 percent of ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

The RESIL-Card tool launches across Europe to strengthen cardiovascular care preparedness against crises

Tools to glimpse how “helicity” impacts matter and light

Smartphone app can help men last longer in bed

Longest recorded journey of a juvenile fisher to find new forest home

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

[Press-News.org] Cool calculations for cold atomsNew theory of universal three-body encounters