(Press-News.org) LEBANON, NH – Doctors trained in locations with less intensive (and expensive) practice patterns appear to consistently be better at making clinical decisions that spare patients unnecessary and excessive medical care, according to a new study in JAMA Internal Medicine.

"Growing concern about the costs and harms of medical care has spurred interest in assessing physicians' ability to avoid the provision of unnecessary care," said lead author Brenda Sirovich of the VA Outcomes Group and The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice.

Sirovich and colleagues sought to evaluate whether residency training influences physicians' capability of making good management decisions, even when those decisions require them to "forgo a wide array of costly medical interventions in favor of management strategies of less intensity, such as watchful waiting." To do this, the investigators developed a measure based on existing questions from the American Board of Internal Medicine certifying exam. On the exam, some questions implicitly assess candidates' ability to manage patients conservatively when such an approach is warranted – that is, questions for which a conservative management strategy was the "right answer."

The authors found that independent of overall medical knowledge, internal medicine exam takers who had trained at programs characterized by lower intensity practice patterns consistently scored higher (better) on the Appropriately Conservative Management exam subscale. These same physicians did just as well, if not better, at recognizing when aggressive management was indicated – a finding that surprised Sirovich and her co-authors.

They conclude that "conservative training environments may promote more thoughtful clinical decision making at both ends – conservative and aggressive – of the spectrum of appropriate practice."

The measure of health care intensity measure the researchers used was physician visits among a comparably ill cohort of patients, but they reported that their findings held for other intensity measures, including spending. Higher regional spending is not associated with better outcomes, satisfaction, or quality of care, and high spending itself leads to more rapid growth in spending, according to previous journal studies published by The Dartmouth Institute on variations in Medicare spending.

"While health care certainly offers important benefits to many, a growing body of evidence points to serious problems of overuse and harm," Sirovich said. Understanding the factors contributing to higher health care utilization has, therefore, become an increasingly important national priority.

She concludes on a hopeful note: "… the possibility that high intensity training environments foster a practice style that may waste precious resources – and harm patients – through inappropriate interventions warrants attention. Reporting feedback to programs about residents' performance on a prospectively designed appropriately conservative management certifying examination subscale might help address the problem of overuse and promote attention to value in medical practice in the United States."

INFORMATION:

To view the abstract of the article in JAMA Internal Medicine, please go to http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3337

The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice was founded in 1988 by Dr. John E. Wennberg as the Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences (CECS). Among its 25 years of accomplishments, it has established a new discipline and educational focus in the Evaluative Clinical Sciences, introduced and advanced the concept of shared decision-making for patients, demonstrated unwarranted variation in the practice and outcomes of medical treatment, developed the first comprehensive examination of US health care variations (The Dartmouth Atlas), and has shown that more health care is not necessarily better care.

Residency training predicts physicians' ability to practice conservatively

2014-09-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Experiences make you happier than possessions -- Before and after

2014-09-02

To get the most enjoyment out of our dollar, science tells us to focus our discretionary spending on experiences such as travel over material goods. A new Cornell University study shows that the enjoyment we derive from experiential purchases may begin even before we buy.

This research offers important information for individual consumers who are trying to "decide on the right mix of material and experiential consumption for maximizing well-being," said psychology researcher and study author Thomas Gilovich of Cornell University.

Previously, Gilovich and colleagues ...

Diabetes mellitus and mild cognitive impairment: Higher risk in middle age?

2014-09-02

Essen, Germany, September 2, 2014 – In a large population-based study of randomly selected participants in Germany, researchers found that mild cognitive impairment (MCI) occurred twice more often in individuals diagnosed with diabetes mellitus type 2. Interestingly, this strong association was only observed in middle-aged participants (50-65 years), whereas in older participants (66-80 years) the association vanished. This study is published in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease.

The concept of MCI describes an intermediate state between normal cognitive aging and dementia. ...

This week From AGU: California earthquake, future Mars rovers, models underestimate ozone

2014-09-02

From AGU's blogs: Earthquake rupture through a U.S. suburb

Observations and mapping by seismologists at the University of California Davis in the hours and days after the August 24 earthquake in northern California are helping scientists understand why the earthquake caused so much damage in the region, according to a post in The Trembling Earth blog, hosted by the American Geophysical Union.

From this week's Eos: Future Mars Rovers: The Next Places to Direct Our Curiosity

Selecting where the next Mars rovers will land involves a series of open-invitation workshops ...

‘Prepped’ by tumor cells, lymphatic cells encourage breast cancer cells to spread

2014-09-02

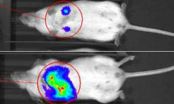

Breast cancer cells can lay the groundwork for their own spread throughout the body by coaxing cells within lymphatic vessels to send out tumor-welcoming signals, according to a new report by Johns Hopkins scientists.

Writing in the Sept. 2 issue of Nature Communications, the researchers describe animal and cell-culture experiments that show increased levels of so-called signaling molecules released by breast cancer cells. These molecules cause lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) in the lungs and lymph nodes to produce proteins called CCL5 and VEGF. CCL5 attracts tumor ...

Cool calculations for cold atoms

2014-09-02

Chemical reactions drive the mechanisms of life as well as a million other natural processes on earth. These reactions occur at a wide spectrum of temperatures, from those prevailing at the chilly polar icecaps to those at work churning near the earth's core. At nanokelvin temperatures, by contrast, nothing was supposed to happen. Chemistry was expected to freeze up. Experiments and theoretical work have now show that this is not true. Even at conditions close to absolute zero atoms can interact and manage to form chemical bonds.

Within this science of ultracold ...

Enzyme controlling metastasis of breast cancer identified

2014-09-02

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have identified an enzyme that controls the spread of breast cancer. The findings, reported in the current issue of PNAS, offer hope for the leading cause of breast cancer mortality worldwide. An estimated 40,000 women in America will die of breast cancer in 2014, according to the American Cancer Society.

"The take-home message of the study is that we have found a way to target breast cancer metastasis through a pathway regulated by an enzyme," said lead author Xuefeng Wu, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher ...

Study links sex hormone levels in the blood to risk of sudden cardiac arrest

2014-09-02

LOS ANGELES (Sept. 2, 2014) – Measuring the levels of sex hormones in patients' blood may identify patients likely to suffer a sudden cardiac arrest, a heart rhythm disorder that is fatal in 95 percent of patients.

A new study, published online by the peer-reviewed journal Heart Rhythm, shows that lower levels of testosterone, the predominant male sex hormone, were found in men who had a sudden cardiac arrest. Higher levels of estradiol, the major female sex hormone, were strongly associated with greater chances of having a sudden cardiac arrest in both men and women. ...

UO-Berkeley Lab unveil new nano-sized synthetic scaffolding technique

2014-09-02

EUGENE, Ore. -- Scientists, including University of Oregon chemist Geraldine Richmond, have tapped oil and water to create scaffolds of self-assembling, synthetic proteins called peptoid nanosheets that mimic complex biological mechanisms and processes.

The accomplishment -- detailed this week in a paper placed online ahead of print by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences -- is expected to fuel an alternative design of the two-dimensional peptoid nanosheets that can be used in a broad range of applications. Among them could be improved chemical sensors ...

Microphysiological systems will revolutionize experimental biology and medicine

2014-09-02

The Annual Thematic issue of Experimental Biology and Medicine that appears in September 2014 is devoted to "The biology and medicine of microphysiological systems" and describes the work of scientists participating in the Microphysiological Systems Program directed by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and funded in part by the NIH Common Fund. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are collaborating with the NIH in the program. Fourteen of ...

An uphill climb for mountain species?

2014-09-02

A recently published paper provides a history of scientific research on mountain ecosystems, looks at the issues threatening wildlife in these systems, and sets an agenda for biodiversity conservation throughout the world's mountain regions.

The paper, "Mountain gloom and mountain glory revisited: A survey of conservation, connectivity, and climate change in mountain regions," appears online in the Journal of Mountain Ecology. Authors are Charles C. Chester of Tufts University, Jodi A. Hilty of the Wildlife Conservation Society, and Lawrence S. Hamilton of World Commission ...