(Press-News.org) Using an "electric prism", scientists have found a new way of separating water molecules that differ only in their nuclear spin states and, under normal conditions, do not part ways. Since water is such a fundamental molecule in the universe, the recent study may impact a multitude of research areas ranging from biology to astrophysics. The research team from the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL) – a collaboration of DESY, the Max Planck Society and Universität Hamburg – reported its results in the journal Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

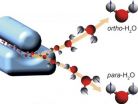

At first glance, water seems to be a simple molecule in which a single oxygen atom is bound to two hydrogen atoms. However, it is more complex when taking into account hydrogen's nuclear spin – a property reminiscent of a rotation of its nucleus about its own axis. The spin of a single hydrogen can assume two different orientations, symbolized as up and down. Thus, the spins of water's two hydrogen atoms can either add up, called ortho water, or cancel out, called para water. Ortho and para states are also said to be symmetric and antisymmetric, respectively.

Fundamental symmetry rules prohibit para water from turning into ortho water and vice versa – at least theoretically. "If you had a magic bottle with isolated para and ortho molecules, they would remain in their spin states at all times," says DESY scientist Jochen Küpper who led the recent study. "In principle, they are different molecular species, different types of water." However, in the real world, water molecules are not isolated and frequently collide with other molecules or surfaces in their vicinity, causing nuclear spin orientations to change. "Through these interactions, para and ortho water can actually transform easily into one another," explains Küpper who is also a professor at the University of Hamburg and a member of the Hamburg Centre for Ultrafast Imaging (CUI). "Therefore, it is very challenging to separate them and produce water that is not a mixture of both."

Yet, the CFEL researchers have now demonstrated a way of isolating para and ortho water in the lab. To start, the scientists placed a drop of water in a compartment, which they pressurized with neon or argon gas. This mixture was released into vacuum through a pulsed valve. "Due to the large pressure difference, the gas expands quickly into the vacuum when the valve is opened, dragging along water molecules and, at the same time, cooling them down," says Daniel Horke, the first author of the study.

This expansion produces a narrow beam of ultracold water molecules, which propagate at supersonic speed and are so dilute that individual molecules no longer collide with each other, thereby suppressing the conversion between para and ortho spin states.

The molecular beam then travels through a strong electric field, which deflects the water molecules from their original flight path and acts like a prism for nuclear spin states. "Para and ortho water interact with the electric field differently," Horke explains. "Thus, they also get deflected differently, allowing us to separate them in space and obtain pure para and ortho samples." Spectroscopy showed that the purity of the para and ortho water was 74 per cent and over 97 per cent, respectively. Especially for para water the purity can be greatly enhanced in the future, as Horke says. Storing the separated water species was not an aim of the study.

The new method could benefit studies of a wide range of phenomena. In astrophysics, for example, it is commonly assumed that the relative amounts of para and ortho species can be linked to the temperature of interstellar ice. This theory is based on the temperature dependence of hydrogen's ortho-to-para ratio, which is three to one at room temperature and drops with decreasing temperatures. "In fact, certain regions of the universe exhibit ratios that are quite different from what you would expect," Horke says. "Yet, the specific reasons are unknown and lab-based experiments could provide new insights."

Back on Earth, the study may also help determine the structures of proteins – biomolecules that are essential to all life. A method known as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy reconstructs protein structures from the relative orientation of the nuclear spins of hydrogen and other atoms. "Para hydrogen has successfully been used to enhance the sensitivity of the NMR method," says Horke. "Thus, enriching para water in a protein's water shell could become an interesting approach to improve NMR spectroscopy of these biological systems due to an almost natural environment."

INFORMATION:

Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron DESY is the leading German accelerator centre and one of the leading in the world. DESY is a member of the Helmholtz Association and receives its funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (90 per cent) and the German federal states of Hamburg and Brandenburg (10 per cent). At its locations in Hamburg and Zeuthen near Berlin, DESY develops, builds and operates large particle accelerators, and uses them to investigate the structure of matter. DESY's combination of photon science and particle physics is unique in Europe.

Researchers part water

'Electric prism' separates water's nuclear spin states

2014-09-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Simeprevir in hepatitis C: Added benefit for certain patients

2014-09-08

The drug simeprevir (trade name: Olysio) has been available since May 2014 for the treatment of adult patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. In an early benefit assessment pursuant to the Act on the Reform of the Market for Medicinal Products (AMNOG), the German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) examined whether this new drug offers an added benefit over the appropriate comparator therapy.

The drug manufacturer dossier provided indications and hints of an added benefit of simeprevir when the patients infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) ...

Plant diversity in China vital for global food security

2014-09-08

With climate change threatening global food supplies, new research claims the rich flora of China could be crucial to underpin food security in the future.

A team from the University of Birmingham and partners in China have identified 871 wild plant species native to China that have the potential to adapt and maintain 28 globally important crops, including rice, wheat, soybean, sorghum, banana, apple, citrus fruits, grape, stone fruits and millet. 42% of these wild plant species, known as crop wild relatives (CWR) occur nowhere else in the world.

CWR are wild plant ...

Plant insights could help develop crops for changing climates

2014-09-08

Crops that thrive in changing climates could be developed more easily, thanks to fresh insights into plant growth.

A new computer model that shows how plants grow under varying conditions could help scientists develop varieties likely to grow well in future.

Scientists built the model to investigate how variations in light, day length, temperature and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere influence the biological pathways that control growth and flowering in plants.

They found differences in the way some plant varieties distribute nutrients under varying conditions, ...

First-ever look inside a working lithium-ion battery

2014-09-08

VIDEO:

Using a neutron beam, chemists and engineers at The Ohio State University were able to track the flow of lithium atoms into and out of an electrode in real time...

Click here for more information.

COLUMBUS, Ohio—For the first time, researchers have been able to open a kind of window into the inner workings of a lithium-ion battery.

Using a neutron beam, chemists and engineers at The Ohio State University were able to track the flow of lithium atoms into and out ...

Targeted immune booster removes toxic proteins in mouse model of Alzheimer's disease

2014-09-08

Alzheimer's disease experts at NYU Langone Medical Center and elsewhere are reporting success in specifically harnessing a mouse's immune system to attack and remove the buildup of toxic proteins in the brain that are markers of the deadly neurodegenerative disease.

Reporting on their experiments in the journal Acta Neuropathologica Communications online Sept. 3, the researchers say the work advances the development of more effective clinical treatments for Alzheimer's because their immune booster reduced both amyloid beta plaques and tau tangles. Previous immunomodulatory ...

Nearly half of older adults have care needs

2014-09-08

Nearly half of older adults – 18 million people—have difficulty or get help with daily activities, according to a new study.

Researchers from the University of Michigan and the Urban Institute analyzed data from a national sample of older adults drawn from Medicare enrollment files. In all, 8,245 people were included in the 2011 the National Health and Aging Trends Study. The analysis was published in the current (September 2014) issue of the Milbank Memorial Quarterly.

"Although 51 percent reported having no difficulty in the previous month, 29 percent reported receiving ...

The future of our crops is at risk in conflict zones, say Birmingham scientists

2014-09-08

Wild species related to our crops which are crucial as potential future food resources have been identified by University of Birmingham scientists, however, a significant proportion are found in conflict zones in the Middle East, where their conservation is increasingly comprised.

The scientists have identified 'hotspots' around the globe where crop wild relatives (CWR) – species closely related to our crops which are needed for future crop variety development – could be conserved in the wild in order to secure future global food resources.

The hotspot where CWR ...

New parasitoid wasp species found in China

2014-09-08

For the first time, wasps in the genus Spasskia (family: Braconidae) have been found in China, according to an article in the open-access Journal of Insect Science. In addition, a species in that genus which is totally new to science was also discovered.

The new species, Spasskia brevicarinata, is very small — male and female adults are less than one centimeter long. It is similar to a previously described species called Spasskia indica, but the ridges on some of its body segments are different. In fact, the species epithet brevicarinata reflects a short ridge on its ...

Unusual immune cell needed to prevent oral thrush, Pitt researchers find

2014-09-08

PITTSBURGH, Sept. 8 – An unusual kind of immune cell in the tongue appears to play a pivotal role in the prevention of thrush, according to the researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine who discovered them. The findings, published online today in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, might shed light on why people infected with HIV or who have other immune system impairments are more susceptible to the oral yeast infection.

Oral thrush is caused by an overgrowth of a normally present fungus called Candida albicans, which leads to painful white lesions ...

'Pick 'n' Mix' chemistry to grow cultures of bioactive molecules

2014-09-08

Chemists at ETH-Zürich and ITbM, Nagoya University have developed a new method to build large libraries of bioactive molecules – which can be used directly for biological assays – by simply mixing a small number of building blocks in water.

Zürich, Switzerland and Nagoya, Japan – Professor Jeffrey Bode of ETH-Zürich and the Institute of Transformative Bio-Molecules (ITbM) of Nagoya University, and his co-worker have established a new strategy called "synthetic fermentation" to rapidly synthesize a large number of bioactive molecules, which can be directly screened in ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

[Press-News.org] Researchers part water'Electric prism' separates water's nuclear spin states