(Press-News.org) Pasadena, CA—Quasars are supermassive black holes that live at the center of distant massive galaxies. They shine as the most luminous beacons in the sky across the entire electromagnetic spectrum by rapidly accreting matter into their gravitationally inescapable centers. New work from Carnegie's Hubble Fellow Yue Shen and Luis Ho of the Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics (KIAA) at Peking University solves a quasar mystery that astronomers have been puzzling over for 20 years. Their work, published in the September 11 issue of Nature, shows that most observed quasar phenomena can be unified with two simple quantities: one that describes how efficiently the hole is being fed, and the other that reflects the viewing orientation of the astronomer.

Quasars display a broad range of outward appearances when viewed by astronomers, reflecting the diversity in the conditions of the regions close to their centers. But despite this variety, quasars have a surprising amount of regularity in their quantifiable physical properties, which follow well-defined trends (referred to as the "main sequence" of quasars) discovered more than 20 years ago. Shen and Ho solved a two-decade puzzle in quasar research: What unifies these properties into this main sequence?

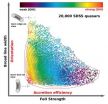

Using the largest and most-homogeneous sample to date of over 20,000 quasars from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, combined with several novel statistical tests, Shen and Ho were able to demonstrate that one particular property related to the accretion of the hole, called the Eddington ratio, is the driving force behind the so-called main sequence. The Eddington ratio describes the efficiency of matter fueling the black hole, the competition between the gravitational force pulling matter inward and the luminosity driving radiation outward. This push and pull between gravity and luminosity has long been suspected to be the primary driver behind the so-called main sequence, and their work at long last confirms this hypothesis.

Of additional importance, they found that the orientation of an astronomer's line-of-sight when looking down into the black hole's inner region plays a significant role in the observation of the fast-moving gas innermost to the hole, which produces the broad emission lines in quasar spectra. This changes scientists' understanding of the geometry of the line-emitting region closest to the black hole, a place called the broad-line region: the gas is distributed in a flattened, pancake-like configuration. Going forward, this will help astronomers improve their measurements of black hole masses for quasars.

"Our findings have profound implications for quasar research. This simple unification scheme presents a pathway to better understand how supermassive black holes accrete matter and interplay with their environments," Shen said.

"And better black hole mass measurements will benefit a variety of applications in understanding the cosmic growth of supermassive black holes and their place in galaxy formation," Ho added.

INFORMATION:

Support for this research was provided by NASA's Hubble Fellowship, awarded by the Space Telescope Science Institute, operated by the Association of Universites for Research in Astronomy Inc. for NASA, the Kavli Foundation, Peking University, and the Chinese Academy of Science through a grant from the Strategic Priority Research Program.

The Carnegie Institution for Science (carnegiescience.edu) is a private, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with six research departments throughout the U.S. Since its founding in 1902, the Carnegie Institution has been a pioneering force in basic scientific research. Carnegie scientists are leaders in plant biology, developmental biology, astronomy, materials science, global ecology, and Earth and planetary science.

Mysterious quasar sequence explained

2014-09-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers discover 3 extinct squirrel-like species

2014-09-10

Paleontologists have described three new small squirrel-like species that place a poorly understood Mesozoic group of animals firmly in the mammal family tree. The study, led by scientists at the American Museum of Natural History and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, supports the idea that mammals—an extremely diverse group that includes egg-laying monotremes such as the platypus, marsupials such as the opossum, and placentals like humans and whales—originated at least 208 million years ago in the late Triassic, much earlier than some previous research suggests. The study ...

Fish and fatty acid consumption associated with lower risk of hearing loss in women

2014-09-10

BOSTON, MA – Researchers at Brigham and Women's Hospital found that consumption of two or more servings of fish per week was associated with a lower risk of hearing loss in women. Findings of the new study Fish and Fatty Acid Consumption and Hearing Loss study led by Sharon G. Curhan, MD, BWH Channing Division of Network Medicine, are published online on September 10 in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (AJCN).

"Acquired hearing loss is a highly prevalent and often disabling chronic health condition," stated Curhan, corresponding author. "Although a decline ...

Research identifies drivers of rich bird biodiversity in Neotropics

2014-09-10

An international team of researchers is challenging a commonly held view that explains how so many species of birds came to inhabit the Neotropics, an area rich in rain forest that extends from Mexico to the southernmost tip of South America. The new research, published today in the journal Nature, suggests that tropical bird speciation is not directly linked to geological and climate changes, as traditionally thought, but is driven by movements of birds across physical barriers such as mountains and rivers that occur long after those landscapes' geological origins.

"The ...

UT Arlington research uses nanotechnology to help cool electrons with no external sources

2014-09-10

A team of researchers has discovered a way to cool electrons to −228 °C without external means and at room temperature, an advancement that could enable electronic devices to function with very little energy.

The process involves passing electrons through a quantum well to cool them and keep them from heating.

The team details its research in "Energy-filtered cold electron transport at room temperature," which is published in Nature Communications on Wednesday, Sept. 10.

"We are the first to effectively cool electrons at room temperature. Researchers have done ...

NASA catches birth of Tropical Storm Odile

2014-09-10

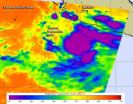

The Eastern Pacific Ocean continues to turn out tropical cyclones and NASA's Aqua satellite caught the birth of the fifteenth tropical depression on September 10 and shortly afterward, it strengthened into a tropical storm and was renamed Odile.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite captured infrared data on Tropical Depression 15-E on September 10 at 8:53 UTC (4:53 a.m. EDT) when it developed. The National Hurricane Center named the depression at 5 a.m. EDT, when the center was located near latitude 14.4 north and ...

A new way to look at diabetes and heart risk

2014-09-10

People with diabetes who appear otherwise healthy may have a six-fold higher risk of developing heart failure regardless of their cholesterol levels, new Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health research suggests.

In nearly 50 percent of people with diabetes in their study, researchers employing an ultra-sensitive test were able to identify minute levels of a protein released into the blood when heart cells die. The finding suggests that people with diabetes may be suffering undetectable – but potentially dangerous – heart muscle damage possibly caused by their ...

Study: Sports broadcasting gender roles echoed on Twitter

2014-09-10

Twitter provides an avenue for female sports broadcasters to break down gender barriers, yet it currently serves to express their subordinate sports media roles.

This is the key finding of a new study by Clemson University researchers and published in the most recent issue of Journal of Sports Media.

"Social media has been embraced by the sports world at an extraordinary pace and has become a viable avenue for sports broadcasters to redefine their roles as celebrities," said Melinda Weathers, lead author on the study and assistant professor of communication studies ...

Cyberbullying increases as students age

2014-09-10

RIVERSIDE, Calif. — As students' age they are verbally and physically bullied less but cyberbullied more, non-native English speakers are not bullied more often than native English speakers and bullying increases as students' transition from elementary to middle school.

Those are among the findings of a wide-ranging paper, "Examination of the Change in Latent Statuses in Bullying Behaviors Across Time," recently published in the journal School Psychology Quarterly.

Authors of the paper are: Cixin Wang, an assistant professor at the University of California, Riverside's ...

Even small stressors may be harmful to men's health, new OSU research shows

2014-09-10

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Older men who lead high-stress lives, either from chronic everyday hassles or because of a series of significant life events, are likely to die earlier than the average for their peers, new research from Oregon State University shows.

"We're looking at long-term patterns of stress – if your stress level is chronically high, it could impact your mortality, or if you have a series of stressful life events, that could affect your mortality," said Carolyn Aldwin, director of the Center for Healthy Aging Research in the College of Public Health and Human ...

Unnecessary antibiotic use responsible for $163 million in potentially avoidable hospital costs

2014-09-10

Arlington, Va. (September 10, 2014) – The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Premier, Inc. have released new research on the widespread use of unnecessary and duplicative antibiotics in U.S. hospitals, which could have led to an estimated $163 million in excess costs. The inappropriate use of antibiotics can increase risk to patient safety, reduce the efficacy of these drugs and drive up avoidable healthcare costs. The study is published in the October issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, the journal of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology ...