(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- Living cells are like miniature factories, responsible for the production of more than 25,000 different proteins with very specific 3-D shapes. And just as an overwhelmed assembly line can begin making mistakes, a stressed cell can end up producing misshapen proteins that are unfolded or misfolded.

Now Duke University researchers in North Carolina and Singapore have shown that the cell recognizes the buildup of these misfolded proteins and responds by reshuffling its workload, much like a stressed out employee might temporarily move papers from an overflowing inbox into a junk drawer.

The study, which appears Sept. 11, 2014 in Cell, could lend insight into diseases that result from misfolded proteins piling up, such as Alzheimer's disease, ALS, Huntington's disease, Parkinson's disease, and type 2 diabetes.

"We have identified an entirely new mechanism for how the cell responds to stress," said Christopher V. Nicchitta, Ph.D., a professor of cell biology at Duke University School of Medicine. "Essentially, the cell remodels the organization of its protein production machinery in order to compartmentalize the tasks at hand."

The general architecture and workflow of these cellular factories has been understood for decades. First, DNA's master blueprint, which is locked tightly in the nucleus of each cell, is transcribed into messenger RNA or mRNA. Then this working copy travels to the ribosomes standing on the surface of a larger accordion-shaped structure called the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The ribosomes on the ER are tiny assembly lines that translate the mRNAs into proteins.

When a cell gets stressed, either by overheating or starvation, its proteins no longer fold properly. These unfolded proteins can set off an alarm -- called the unfolded protein response or UPR – to slow down the assembly line and clean up the improperly folded products. Nicchitta wondered if the stress response might also employ other tactics to deal with the problem.

In this study, Nicchitta and his colleagues treated tissue culture cells with a stress-inducing agent called thapsigargin. They then separated the cells into two groups -- those containing mRNAs associated with ribosomes on the endoplasmic reticulum, and those containing mRNAs associated with free-floating ribosomes in the neighboring fluid-filled space known as the cytosol.

The researchers found that when the cells were stressed, they quickly moved mRNAs from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol. Once the stress was resolved, the mRNAs went back to their spots on the production floor of the endoplasmic reticulum.

"You can slow down protein production, but sometimes slowing down the workflow is not enough," Nicchitta said. "You can activate genes to help chew up the misfolded proteins, but sometimes they are accumulating too quickly. Here we have discovered a mechanism that does one better -- it effectively puts everything on hold. Once things get back to normal, the mRNAs are released from the holding pattern."

Interestingly, the researchers found that shuttling ribosomes between the ER and the cytoplasm during stress only affected the subset of mRNAs that would give rise to secreted proteins like hormones or membrane proteins like growth factor receptors -- the types of proteins that set off the stress response if they're misfolded. They aren't sure yet what this means.

Nicchitta is currently searching for the factors that ultimately determine which mechanisms cells employ during the stress response. He has already pinpointed one promising candidate, and is looking to see how cells respond to stress when that factor is manipulated.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM101533) and the Singapore Ministry of Health (Duke/Duke-NUS Research Collaboration Award).

CITATION: "The Unfolded Protein Response Triggers Selective mRNA Release From the Endoplasmic Reticulum," David W. Reid, Qiang Chen, Angeline S.-L. Tay, Shirish Shenolikar, and Christopher V. Nicchitta. Cell, September 11, 2014.

Cells put off protein production during times of stress

High error rate on production line triggers slowdown

2014-09-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

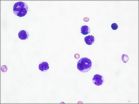

A non-toxic strategy to treat leukemia

2014-09-11

A study comparing how blood stem cells and leukemia cells consume nutrients found that cancer cells are far less tolerant to shifts in their energy supply than their normal counterparts. The results suggest that there could be ways to target leukemia metabolism so that cancer cells die but other cell types are undisturbed.

Harvard Stem Cell Institute scientists at the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Regenerative Medicine and the Harvard University Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology led the work, published in the journal Cell, in collaboration with ...

Scientists discover neurochemical imbalance in schizophrenia

2014-09-11

Using human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), researchers at Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at University of California, San Diego have discovered that neurons from patients with schizophrenia secrete higher amounts of three neurotransmitters broadly implicated in a range of psychiatric disorders.

The findings, reported online Sept. 11 in Stem Cell Reports, represent an important step toward understanding the chemical basis for schizophrenia, a chronic, severe and disabling brain disorder that affects an estimated one in 100 persons at some ...

Diverse gut bacteria associated with favorable ratio of estrogen metabolites

2014-09-11

Washington, DC—Postmenopausal women with diverse gut bacteria exhibit a more favorable ratio of estrogen metabolites, which is associated with reduced risk for breast cancer, compared to women with less microbial variation, according to a new study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM).

Since the 1970s, it has been known that in addition to supporting digestion, the intestinal bacteria that make up the gut microbiome influence how women's bodies process estrogen, the primary female sex hormone. The colonies of bacteria ...

Puerto Ricans who inject drugs among Latinos at highest risk of contracting HIV

2014-09-11

Higher HIV risk behaviors and prevalence have been reported among Puerto Rican people who inject drugs (PRPWID) since early in the HIV epidemic. Now that HIV prevention and treatment advances have reduced HIV among PWID in the US, researchers from New York University's Center for Drug Use and HIV Research (CDUHR) examined HIV-related data for PRPWID in Puerto Rico (PR) and Northeastern US (NE) to assess whether disparities among PRPWID continue.

The study, "Addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic among Puerto Rican people who inject drugs: the Need for a Multi-Region Approach," ...

Chemical signals in the brain help guide risky decisions

2014-09-11

A gambler's decision to stay or fold in a game of cards could be influenced by a chemical in the brain, suggests new research from the University of British Columbia.

The rise and fall of dopamine plays a key role in decisions involving risk and reward, from a baseball player trying to steal a base to an investor buying or selling a stock. Previous studies have shown that dopamine signals increase when risky choices pay off.

"Our brains are constantly updating how we calculate risk and reward based on previous experiences, keeping an internal score of wins and losses," ...

Mice and men share a diabetes gene

2014-09-11

A joint work by EPFL, ETH Zürich and the CHUV has identified a pathological process that takes place in both mice and humans towards one of the most common diseases that people face in the industrialized world: type 2 diabetes.

This work was conducted in Johan Auwerx's (EPFL) and Ruedi Aebersold's (ETH Zürich) laboratories, and succeeded thanks to the combination of each team's strengths. The relevance of their discovery, published today in Cell Metabolism, results from their joint effort.

In Lausanne, the researchers carried out a detailed study of the genome and ...

Compound protects brain cells after traumatic brain injury

2014-09-11

A new class of compounds has now been shown to protect brain cells from the type of damage caused by blast-mediated traumatic brain injury (TBI). Mice that were treated with these compounds 24-36 hours after experiencing TBI from a blast injury were protected from the harmful effects of TBI, including problems with learning, memory, and movement.

Traumatic brain injury caused by blast injury has emerged as a common health problem among U.S. servicemen and women, with an estimated 10 to 20 percent of the more than 2 million U.S. soldiers deployed in Iraq or Afghanistan ...

Proactive monitoring of inflammatory bowel disease therapy could prolong effectiveness

2014-09-11

BOSTON – Proactive monitoring and dose adjustment of infliximab, a medication commonly used to treat inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), could improve a patient's chances of having a long-term successful response to therapy, a pilot observational study at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center concludes.

The study, published in the Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, evaluated the levels of infliximab, an antibody designed to bind to and block the effects of TNF-alpha, an inflammatory protein found in high levels in patients with IBD, such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, ...

LSU scientists lead research on speciation in the tropics

2014-09-11

BATON ROUGE – In a study that sheds light on the origin of bird species in the biologically rich rainforests of South America, LSU Museum of Natural Science Director and Roy Paul Daniels Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, Robb Brumfield, and an international team of researchers funded by the National Science Foundation, or NSF, published a paper this week challenging the view that speciation – the process by which new species are formed – is directly linked to geological and climatic changes to the landscape.

The researchers, whose findings were published ...

Microscopic diamonds suggest cosmic impact responsible for major period of climate change

2014-09-11

Around 12,800 years ago, a sudden, catastrophic event plunged much of the Earth into a period of cold climatic conditions and drought. This drastic climate change—the Younger Dryas—coincided with the extinction of Pleistocene megafauna, such as the saber-tooth cats and the mastodon, and resulted in major declines in prehistoric human populations, including the termination of the Clovis culture.

With limited evidence, several rival theories have been proposed about the event that sparked this period, such as a collapse of the North American ice sheets, a major volcanic ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

App aids substance use recovery in vulnerable populations

College students nationwide received lifesaving education on sudden cardiac death

Oak Ridge National Laboratory launches the Next-Generation Data Centers Institute

Improved short-term sea level change predictions with better AI training

UAlbany researchers develop new laser technique to test mRNA-based therapeutics

New water-treatment system removes nitrogen, phosphorus from farm tile drainage

Major Canadian study finds strong link between cannabis, anxiety and depression

New discovery of younger Ediacaran biota

Lymphovenous bypass: Potential surgical treatment for Alzheimer's disease?

When safety starts with a text message

[Press-News.org] Cells put off protein production during times of stressHigh error rate on production line triggers slowdown