(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON, DC—In the early morning hours of March 4, 2002, military officers in Bagram, Afghanistan desperately radioed a Chinook helicopter headed for the snowcapped peak of Takur Ghar. On board were 21 men, deployed to rescue a team of Navy SEALS pinned down on the ridge dividing the Upper and Lower Shahikot valley. The message was urgent: Do not land on the peak. The mountaintop was under enemy control.

The rescue team never got the message. Just after daybreak, the Chinook crash-landed on the peak under heavy enemy fire and three men were killed in the ensuing firefight.

A decade later, Michael Kelly, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), happened to read a journalistic account of Operation Anaconda, one of the first major battles of the War in Afghanistan, and thought radio operators may have been thwarted by a little-known source of radio interference: plasma bubbles.

Now, Kelly and his colleagues provide evidence that plasma bubbles may have contributed to the communications outages during the battle of Takur Ghar and present a new computer model that could help predict the impact of such bubbles on future military operations. Their work has been accepted for publication in a journal of the American Geophysical Union called Space Weather.

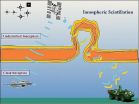

Giant plasma bubbles –wispy clouds of electrically charged gas particles – form after dark in the upper atmosphere. Typically around 100 kilometers (62 miles) wide, the bubbles can't be seen but they can bend and disperse radio waves, interfering with communications.

Plasma is pervasive in the upper atmosphere during daylight hours when the sun's radiation rips electrons from atoms and molecules. Sunlight keeps the plasma stable during the day, but at night, the charged particles recombine to form electrically neutral atoms and molecules again. This recombination happens faster at lower altitudes, making the plasma there less dense, so that it bubbles up through the denser plasma above, like air bubbles rising through water. The rising tendrils of low-density, charged particles are called plasma bubbles, and turbulence at their edges can skew radio frequency waves passing through them.

In the atmosphere above Afghanistan, peak bubble season generally occurs during the spring, according to the study's authors. Given the timing and location of the battle of Takur Ghar, the researchers thought these atmospheric anomalies could have been present.

To confirm their suspicions, Kelly's team looked at data from the Global Ultraviolet Imager(GUVI) instrument aboard NASA's Thermosphere, Ionosphere, Mesosphere Energetics and Dynamics (TIMED) mission, which launched in 2001 to study the composition and dynamics of the upper atmosphere.

"The TIMED spacecraft flew over the battle field at about the right time," said Kelly, the lead author of the new study. That was a stroke of luck for the researchers, Kelly noted—and realizing that that spacecraft might have been there was a breakthrough moment.

Joseph Comberiate, a space physicist at APL and a co-author of the new study, developed a technique to transform the two-dimensional satellite images into three-dimensional representations of plasma bubbles. Using this technique, the authors were able to show that on March 4, 2002 there was a plasma bubble directly between the ill-fated Chinook and the communications satellite. The new model shows the electron-depleted regions of the atmosphere where radio wave interference, known as scintillation, is most likely to occur.

The plasma bubble that was present during the battle of Takur Ghar was probably not large enough to disturb radio communications by itself, but likely contributed to the radio interference caused by the complex terrain in the area, according to the new study. Both factors ultimately led to the black-out in communications between the operations center and the helicopter, the new research says.

In that kind of terrain, the radio equipment was already "operating out on the edge," said Kelly. Losing a few decibels of radio signal due to plasma bubbles "could have pushed them over the edge," he suggested.

The new model could be used to minimize the impacts of plasma bubbles in the future by detecting and predicting their movement for several hours after they form, the researchers said. The model combines data from several different satellite-based systems to detect the bubbles and uses wind and atmospheric models to predict where they will drift.

By identifying these turbulent bubbles and their paths in real time, soldiers may be able to predict when and where they will experience radio interferences and adapt by using a different radio frequency or some other means of communication, said Comberiate. The group is currently working to validate the new model so it can be used in future military operations.

"The most exciting part for me is to see something go from science to real, potential operational impact," he said.

INFORMATION:

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing more than 62,000 members in 144 countries. Join our conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other social media channels.

'Space bubbles' may have aided enemy in fatal Afghan battle

2014-09-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

This week from AGU: New geologic map of Mars, storm surge in Florida

2014-09-23

From this week's Eos: The New Geologic Map of Mars: Guiding Research and Education

Currently, five spacecraft are investigating Mars, and a swarm of new missions to the Red Planet either have been launched or are in development. They are designed to probe the surface, subsurface, and atmosphere with a host of scientific instruments. Where will they make new discoveries? Clues to where they should focus investigations can be gleaned from the planet's new geologic map.

From AGU's journals: History of storm surge in Florida strongly underestimated

The observational ...

Water-quality trading can reduce river pollution

2014-09-23

DURHAM, N.C. -- Allowing polluters to buy, sell or trade water-quality credits could significantly reduce pollution in river basins and estuaries faster and at lower cost than requiring the facilities to meet compliance costs on their own, a new Duke University-led study finds.

The scale and type of the trading programs, though critical, may matter less than just getting them started.

"Our analysis shows that water-quality trading of any kind can significantly lower the costs of achieving Clean Water Act goals," said Martin W. Doyle, professor of river science and policy ...

State policies are effective in reducing power plant emissions, CU-led study finds

2014-09-23

A new study led by the University of Colorado Boulder found that different strategies used by states to reduce power plant emissions -- direct ones such as emission caps and indirect ones like encouraging renewable energy -- are both effective. The study is the first analysis of its kind.

The findings are important because the success of the Environmental Protection Agency's proposed Clean Power Plan depends on the effectiveness of states' policies in reducing power plants' carbon dioxide emissions. The plan would require each state to cut CO2 pollution from power plants ...

Big changes in the Sargasso Sea

2014-09-23

Over one thousand miles wide and three thousand miles long, the Sargasso Sea occupies almost two thirds of the North Atlantic Ocean. Within the sea, circling ocean currents accumulate mats of Sargassum seaweed that shelter a surprising variety of fishes, snails, crabs, and other small animals. A recent paper by MBARI researcher Crissy Huffard and others shows that in 2011 and 2012 this animal community was much less diverse than it was in the early 1970s, when the last detailed studies were completed in this region.

This study was based on field research led by MBARI ...

Study finds gallbladder surgery can wait

2014-09-23

LOS ANGELES – (September 23, 2014) –Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, a minimally invasive procedure to remove the gallbladder, is one of the most common abdominal surgeries in the U.S. Yet medical centers around the country vary in their approaches to the procedure with some moving patients quickly into surgery while others wait.

In a study published online Monday in the American Journal of Surgery, researchers found gallbladder removal surgery can wait until regular working hours rather than rushing the patients into the operating room at night.

"The urgency of removing ...

'Bendy' LEDs

2014-09-23

VIDEO:

This is an animation of the micro-rod growth process.

Click here for more information.

WASHINGTON D.C., Sept. 23, 2014 -- "Bendy" light-emitting diode (LED) displays and solar cells crafted with inorganic compound semiconductor micro-rods are moving one step closer to reality, thanks to graphene and the work of a team of researchers in Korea.

Currently, most flexible electronics and optoelectronics devices are fabricated using organic materials. But inorganic compound ...

Diabetes: Complexity lost

2014-09-23

WASHINGTON, D.C., September 23, 2014 -- For millions of people in the United States living with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes, measuring the daily rise and fall of blood glucose (sugar) is a way of life.

Our body's energy is primarily governed by glucose in the blood, and blood sugar itself is exquisitely controlled by a complicated set of network interactions involving cells, tissues, organs and hormones that have evolved to keep the glucose on a relatively even keel, pumping it up when it falls too low or knocking it down when it goes too high. This natural dynamical balance ...

Future flexible electronics based on carbon nanotubes

2014-09-23

WASHINGTON, D.C., September 23, 2014—Researchers from the University of Texas at Austin and Northwestern University have demonstrated a new method to improve the reliability and performance of transistors and circuits based on carbon nanotubes (CNT), a semiconductor material that has long been considered by scientists as one of the most promising successors to silicon for smaller, faster and cheaper electronic devices. The result appears in a new paper published in the journal Applied Physics Letters, from AIP Publishing.

In the paper, researchers examined the effect ...

Lack of sleep increases risk of failure in school

2014-09-23

A new Swedish study shows that adolescents who suffer from sleep disturbance or habitual short sleep duration are less likely to succeed academically compared to those who enjoy a good night's sleep. The results have recently been published in the journal Sleep Medicine.

In a new study involving more than 20,000 adolescents aged between 12 and 19 from Uppsala County, researchers from Uppsala University demonstrate that reports of sleep disturbance and habitual short sleep duration (less than 7 hours per day) increased the risk of failure in school.

The study was led ...

Moving to the 'burbs is bad for business

2014-09-23

This news release is available in French. Montreal, September 23, 2014 — It's rare to see a Wal-Mart downtown. Big box stores usually set up shop in the suburbs, where rent is cheap and the consumer base is growing. So should smaller stores follow suit?

Not so fast, says Concordia University professor Tieshan Li. His recent study, published in the Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, shows that higher profits are had by retailers located furthest from where the market is expanding.

"Those results may seem counterintuitive but the decreased profits are ...