(Press-News.org) Scientists often measure the effects of temperature on insects to predict how climate change will affect their distribution and abundance, but a Dartmouth study shows for the first time that insects' fear of their predators, in addition to temperature, ultimately limits how fast they grow.

"In other words, it's less about temperature and more about the overall environmental conditions that shape the growth, survival and distribution of insects." says the study's lead author Lauren Culler, an Arctic postdoctoral researcher at Dartmouth.

The study appears in the journal Oecologia. A PDF is available on request.

Animals live in a constantly changing physical and biological environment, and the fear of being eaten can drastically alter their behavior, physiology, growth and population dynamics. That fear, known as the "flight-or-fight" response, can prompt physiological responses that stunt their growth and reproductive capability, either because they spend less time foraging for food and more time hiding or because they produce anti-predator defenses that can be energetically costly.

Previous studies have shown that warming temperatures make insects eat more and grow faster. The Dartmouth study looked at how fear, which typically lowers food consumption and growth rate, affects an insects' response to warming temperatures. They brought damselflies into the lab and measured how much they ate and grew at different temperatures and how that changed when a fish predator was nearby. They used an experimental setup in which a damselfly was floated in a glass vial and exposed visually and chemically to a fish predator.

The results showed that in the absence of fear, the damselflies ate more food and grew faster as the temperature increased. Surprisingly, however, when a fish predator was looming, the damselflies ate about the same amount of food but grew much more slowly. The researchers aren't sure what happens to the food that doesn't go into growth, but they think it gets lost in the anti-predator response, possibly to production of stress proteins.

"Studies that aim to predict the consequences of climate change on insect populations should consider additional factors that may ultimately limit growth and survival, such as the risk of being eaten by a predator," Culler says.

INFORMATION:

Postdoctoral researcher Lauren Culler is available to comment at leculler@gmail.com

Broadcast studios: Dartmouth has TV and radio studios available for interviews. For more information, visit: http://www.dartmouth.edu/~opa/radio-tv-studios/

Insects' fear limits boost from climate change, Dartmouth study shows

2014-09-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Kessler Foundation researchers find foot drop stimulator beneficial in stroke rehab

2014-09-23

West Orange, NJ. September 23, 2014. Kessler Foundation scientists have published a study showing that use of a foot drop stimulator during a task-specific movement for 4 weeks can retrain the neuromuscular system. This finding indicates that applying the foot drop stimulator as rehabilitation intervention may facilitate recovery from this common complication of stroke. "EMG of the tibialis anterior demonstrates a training effect after utilization of a foot drop stimulator," was published online ahead of print on July 2 by NeuroRehabilitation (doi:10.3233/NRE-141126). The ...

'Brain Breaks' increase activity, educational performance in elementary schools

2014-09-23

CORVALLIS, Ore. – A recent Oregon survey about an exercise DVD that adds short breaks of physical activity into the daily routine of elementary school students found it had a high level of popularity with both students and teachers, and offered clear advantages for overly sedentary educational programs.

Called "Brain Breaks," the DVD was developed and produced by the Healthy Youth Program of the Linus Pauling Institute at Oregon State University, and is available nationally.

Brain Breaks leads children in 5-7 minute segments of physical activity, demonstrated by OSU ...

Surveys may assess language more than attitudes, says study involving CU-Boulder

2014-09-23

Scientists who study patterns in survey results might be dealing with data on language rather than what they're really after -- attitudes -- according to an international study involving the University of Colorado Boulder.

The study, published in the journal PLOS ONE, found that people naturally responded to surveys by selecting answer options that were similar in language to each other as they navigated from one question to another, even when the similarities were subtle.

For the study, researchers looked specifically at surveys on organizational behavior, such as ...

Researchers reveal new rock formation in Colorado

2014-09-23

Boulder, Colo., USA - An astonishing new rock formation has been revealed in the Colorado Rockies, and it exists in a deeply perplexing relationship with older rocks. Named the Tava sandstone, this sedimentary rock forms intrusions within the ancient granites and gneisses that form the backbone of the Front Range. The relationship is fascinating because it is backward: ordinarily, it is igneous rocks such as granite that would that intrude into sedimentary rocks.

According to authors Christine Smith Siddoway and George E. Gehrels, to find sandstone injected into granite ...

Note to young men: Fat doesn't pay

2014-09-23

Men who are already obese as teenagers could grow up to earn up to 18 percent less than their peers of normal weight. So says Petter Lundborg of Lund University, Paul Nystedt of Jönköping University and Dan-olof Rooth of Linneas University and Lund University, all in Sweden. The team compared extensive information from Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States, and the results are published in Springer's journal Demography.

The researchers analyzed large-scale data of 145,193 Swedish-born brothers who enlisted in the Swedish National Service for mandatory military ...

Immune system is key ally in cyberwar against cancer

2014-09-23

Research by Rice University scientists who are fighting a cyberwar against cancer finds that the immune system may be a clinician's most powerful ally.

"Recent research has found that cancer is already adept at using cyberwarfare against the immune system, and we studied the interplay between cancer and the immune system to see how we might turn the tables on cancer," said Rice University's Eshel Ben-Jacob, co-author of a new study this week in the Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Ben-Jacob and colleagues at Rice's Center for Theoretical ...

UTSA microbiologists discover regulatory thermometer that controls cholera

2014-09-23

Karl Klose, professor of biology and a researcher in UTSA's South Texas Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases, has teamed up with researchers at Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany to understand how humans get infected with cholera, Their findings were released this week in an article published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Cholera is an acute infection caused by ingestion of food or water that is contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. An estimated three to five million cases are reported annually and 100,000-120,000 people die from ...

'Space bubbles' may have aided enemy in fatal Afghan battle

2014-09-23

WASHINGTON, DC—In the early morning hours of March 4, 2002, military officers in Bagram, Afghanistan desperately radioed a Chinook helicopter headed for the snowcapped peak of Takur Ghar. On board were 21 men, deployed to rescue a team of Navy SEALS pinned down on the ridge dividing the Upper and Lower Shahikot valley. The message was urgent: Do not land on the peak. The mountaintop was under enemy control.

The rescue team never got the message. Just after daybreak, the Chinook crash-landed on the peak under heavy enemy fire and three men were killed in the ensuing firefight.

A ...

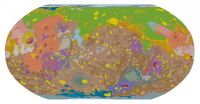

This week from AGU: New geologic map of Mars, storm surge in Florida

2014-09-23

From this week's Eos: The New Geologic Map of Mars: Guiding Research and Education

Currently, five spacecraft are investigating Mars, and a swarm of new missions to the Red Planet either have been launched or are in development. They are designed to probe the surface, subsurface, and atmosphere with a host of scientific instruments. Where will they make new discoveries? Clues to where they should focus investigations can be gleaned from the planet's new geologic map.

From AGU's journals: History of storm surge in Florida strongly underestimated

The observational ...

Water-quality trading can reduce river pollution

2014-09-23

DURHAM, N.C. -- Allowing polluters to buy, sell or trade water-quality credits could significantly reduce pollution in river basins and estuaries faster and at lower cost than requiring the facilities to meet compliance costs on their own, a new Duke University-led study finds.

The scale and type of the trading programs, though critical, may matter less than just getting them started.

"Our analysis shows that water-quality trading of any kind can significantly lower the costs of achieving Clean Water Act goals," said Martin W. Doyle, professor of river science and policy ...