(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Bacillus anthracis bacteria have very efficient machinery for injecting toxic proteins into cells, leading to the potentially deadly infection known as anthrax. A team of MIT researchers has now hijacked that delivery system for a different purpose: administering cancer drugs.

"Anthrax toxin is a professional at delivering large enzymes into cells," says Bradley Pentelute, the Pfizer-Laubauch Career Development Assistant Professor of Chemistry at MIT. "We wondered if we could render anthrax toxin nontoxic, and use it as a platform to deliver antibody drugs into cells."

In a paper appearing in the journal ChemBioChem, Pentelute and colleagues showed that they could use this disarmed version of the anthrax toxin to deliver two proteins known as antibody mimics, which can kill cancer cells by disrupting specific proteins inside the cells. This is the first demonstration of effective delivery of antibody mimics into cells, which could allow researchers to develop new drugs for cancer and many other diseases, says Pentelute, the senior author of the paper.

Hitching a ride

Antibodies — natural proteins the body produces to bind to foreign invaders — are a rapidly growing area of pharmaceutical development. Inspired by natural protein interactions, scientists have designed new antibodies that can disrupt proteins such as the HER2 receptor, found on the surfaces of some cancer cells. The resulting drug, Herceptin, has been successfully used to treat breast tumors that overexpress the HER2 receptor.

Several antibody drugs have been developed to target other receptors found on cancer-cell surfaces. However, the potential usefulness of this approach has been limited by the fact that it is very difficult to get proteins inside cells. This means that many potential targets have been "undruggable," Pentelute says.

"Crossing the cell membrane is really challenging," he says. "One of the major bottlenecks in biotechnology is that there really doesn't exist a universal technology to deliver antibodies into cells."

For inspiration to solve this problem, Pentelute and his colleagues turned to nature. Scientists have been working for decades to understand how anthrax toxins get into cells; recently researchers have started exploring the possibility of mimicking this system to deliver small protein molecules as vaccines.

The anthrax toxin has three major components. One is a protein called protective antigen (PA), which binds to receptors called TEM8 and CMG2 that are found on most mammalian cells. Once PA attaches to the cell, it forms a docking site for two anthrax proteins called lethal factor (LF) and edema factor (EF). These proteins are pumped into the cell through a narrow pore and disrupt cellular processes, often resulting in the cell's death.

However, this system can be made harmless by removing the sections of the LF and EF proteins that are responsible for their toxic activities, leaving behind the sections that allow the proteins to penetrate cells. The MIT team then replaced the toxic regions with antibody mimics, allowing these cargo proteins to catch a ride into cells through the PA channel.

'A prominent advance'

The antibody mimics are based on protein scaffolds that are smaller than antibodies but still maintain structural diversity and can be designed to target different proteins inside a cell. In this study, the researchers successfully targeted several proteins, including Bcr-Abl, which causes chronic myeloid leukemia; cancer cells in which that protein was disrupted underwent programmed cell suicide. The researchers also successfully blocked hRaf-1, a protein that is overactive in many cancers.

The MIT team is now testing this approach to treat tumors in mice and is also working on ways to deliver the antibodies to specific types of cells.

INFORMATION:

Lead authors of the paper are postdoc Xiaoli Liao and graduate student Amy Rabideau. The research was funded by the MIT Reed Fund, the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation, and the National Science Foundation.

Chemists recruit anthrax to deliver cancer drugs

2014-09-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists develop tool to help communities stay environmentally and socially 'healthy'

2014-09-25

Geographers at the University of Southampton have developed a new way to measure the 'health' of poor regional communities. They aim to improve the wellbeing of people by guiding sustainable development practices to help avoid social and environmental collapse.

The researchers have pioneered a methodology that examines the balance between factors such as; standards of living, natural resources, agriculture, industry and the economy. The results help identify critical limits, beyond which regions risk tipping into ecological and social downturn, or even collapse.

The ...

Experts at LSTM use modelling approach to assess the effectiveness TB diagnostics

2014-09-25

Experts at LSTM have used a novel modelling approach to project the effects of new diagnostic methods and algorithms for the diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB) recently endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO), looking at the patient, health system and population perspective in Tanzania.

In a paper published in the journal The Lancet Global Health, LSTM's Ivor Langley and Professor Bertie Squire worked with colleagues from the Institute of Epidemiology and Preventative Medicine, National Taiwan University; National Tuberculosis and leprosy Programme, Tanzania; Department ...

Simple blood test could be used as tool for early cancer diagnosis

2014-09-25

High levels of calcium in blood, a condition known as hypercalcaemia, can be used by GPs as an early indication of certain types of cancer, according to a study by researchers from the universities of Bristol and Exeter.

Hypercalcaemia is the most common metabolic disorder associated with cancer, occurring in 10 to 20 per cent of people with cancer. While its connection to cancer is well known, this study has, for the first time, shown that often it can predate the diagnosis of cancer in primary care.

A simple blood test could identify those with hypercalcaemia, prompting ...

Perfectionism is a bigger than perceived risk factor in suicide: York U psychology expert

2014-09-25

TORONTO, September 25, 2014 – Perfectionism is a bigger risk factor in suicide than we may think, says York University Psychology Professor Gordon Flett, calling for closer attention to its potential destructiveness, adding that clinical guidelines should include perfectionism as a separate factor for suicide risk assessment and intervention.

"There is an urgent need for looking at perfectionism with a person-centred approach as an individual and societal risk factor, when formulating clinical guidelines for suicide risk assessment and intervention, as well as public ...

New findings on how brain handles tactile sensations

2014-09-25

The traditional understanding in neuroscience is that tactile sensations from the skin are only assembled to form a complete experience in the cerebral cortex, the most advanced part of the brain. However, this is challenged by new research findings from Lund University in Sweden that suggest both that other levels in the brain play a greater role than previously thought, and that a larger proportion of the brain's different structures are involved in the perception of touch.

"It was believed that a tactile sensation, such as touching a simple object, only activated a ...

Massive weight loss increases risk of complications in body-shaping surgery

2014-09-25

DALLAS – Sept. 25, 2014 – Patients who lost more than 100 pounds and those who shed weight through bariatric surgery had the highest risk of complications from later surgical procedures to reshape their leaner bodies, a new study from UT Southwestern Medical Center shows.

The study, published in the Aesthetic Surgery Journal, compared surgical complication outcomes for 450 patients who underwent body contouring, a type of surgery to remove excess sagging fat and skin to improve body shape.

"This is one of the first large-scale studies comparing outcomes in patients ...

Natural selection causes early migration and shorter parental care for shorebirds

2014-09-25

All bird migrations are fraught with danger – from the risk of not finding enough food, to facing stormy weather, and most importantly – trying not to be eaten along the way. Raptors such as peregrine falcons (see picture) are the main predators of migratory birds, and huge flocks of congregating shorebirds can be easy pickings. In a paper, just published in Animal Migration, an open access journal by De Gruyter Open, Dr. Sarah Jamieson and her colleagues provide new evidence that shorebird species can adopt substantially different ways of dealing with this predation pressure.

It ...

Spot on against autoimmune diseases and chronic inflammations

2014-09-25

This news release is available in German.

The immune system functions as the body's police force, protecting it from intruders like bacteria and viruses. However, in order to ascertain what is happening in the cell it requires information on the foreign invaders. This task is assumed by so-called immunoproteasomes. These are cylindrical protein complexes that break down the protein structures of the intruders into fragments that can be used by the defense system.

"In autoimmune disorders like rheumatism, type 1 diabetes or multiple sclerosis as well as severe ...

Discovery may lead to better treatments for autoimmune diseases, bone loss

2014-09-25

Scientists have developed an approach to creating treatments for osteoporosis and autoimmune diseases that may avoid the risk of infection and cancer posed by some current medications.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis redesigned a molecule that controls immune cell activity, changing the molecule's target and altering the effects of the signal it sends.

Current treatments for bone loss and autoimmune disorders block these molecules and their signals indiscriminately, which over time increases the risk of infections and cancer. The ...

Fossil of multicellular life moves evolutionary needle back 60 million years

2014-09-25

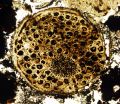

A Virginia Tech geobiologist with collaborators from the Chinese Academy of Sciences have found evidence in the fossil record that complex multicellularity appeared in living things about 600 million years ago – nearly 60 million years before skeletal animals appeared during a huge growth spurt of new life on Earth known as the Cambrian Explosion.

The discovery published online Wednesday in the journal Nature contradicts several longstanding interpretations of multicellular fossils from at least 600 million years ago.

"This opens up a new door for us to shine some light ...