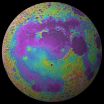

(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Oceanus Procellarum, a vast dark patch visible on the western edge of the Moon's near side, has long been a source of mystery for planetary scientists. Some have suggested that the "ocean of storms" is part of a giant basin formed by an asteroid impact early in the Moon's history. But new research published today in Nature deals a pretty big blow to the impact theory.

The new study, based on data from NASA's GRAIL mission, found a series of linear gravitational anomalies forming a giant rectangle, nearly 1,600 miles across, running beneath the Procellarum region. Those anomalies appear to be the remnants of ancient rifts in the Moon's crust, say the authors of the new study. The rifts provided a vast "magma plumbing system" that flooded the region with volcanic lava between 3 and 4 billion years ago. That giant flux of lava solidified to form the dark basalts we see from Earth.

It's the shape of the underlying gravity anomalies that cast doubt on impact hypothesis, said Jim Head, the Louis and Elizabeth Scherck Distinguished Professor of Geological Sciences at Brown and one of the authors of the new paper.

"Instead of a central circular gravity anomaly like all other impact basins, at Procellarum we see these linear features forming this huge rectangle," Head said. "This shape argues strongly for an internal origin and suggests internal forces."

The research team, led by Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna of the Colorado School of Mines, suggests a new hypothesis for just what those internal forces may have been. The process, the researchers believe, was driven by the geochemical composition of the Moon's crust in the Procellarum region.

Early in its history, the Moon is believed to have been entirely covered in molten magma, which slowly cooled to form the crust. However, the Procellarum region is known to have a high concentration of uranium, thorium, and potassium — radioactive elements that produce heat. The researchers believe those elements may have caused Procellarum to cool and solidify after the rest of the crust had already cooled. When Procellarum did finally cool, it shrank and pulled away from the surrounding crust, forming the giant rifts seen in the new data. Magma flowed into those rifts and flooded the region.

"We think this is a really good, testable alternative to the impact basin theory," said Head. "Everything we see suggests that internal forces were critical in the formation of Procellarum."

New mission, old debate

The familiar face of the Moon's near side is dominated by the lunar maria, the dark patches etched across the surface. Most of the large circular features — like Mare Serenitatis (Sea of Serenity) and Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains) — have been shown to be impact basins that later filled with volcanic lava, which eventually cooled to form the dark basalts. Samples gathered during the Apollo missions, and data gathered by subsequent unmanned missions, helped to confirm that idea.

But the origin of Oceanus Procellarum remained up in the air, largely because it simply doesn't look like the known basins. It is shaped a bit like a horseshoe, while the other basins are round. Procellarum also lacks surrounding mountains and radial grooves scoured by impact ejecta, both telltale signs of an impact basin.

Still, the idea that Procellarum was indeed formed by an impact surfaced in the mid-1970s. Proponents of the impact theory argued that Procellarum looked different simply because it was much older than the other basins. Because of its age, the telltale mountains and grooves had been eroded away, and debris had partially filled the basin's midsection, giving it the horseshoe shape.

Finally settling the debate required a mission like GRAIL, Head said. The mission is led by Maria Zuber, who earned her Ph.D. at Brown and is now vice president of research at MIT. The twin GRAIL spacecraft, which orbited the Moon in 2012, made detailed maps of the Moon's gravity. Those maps have revealed important details about the Moon's subsurface crust.

"It's like putting the crust under an X-ray," Head said. "We can go into the subsurface and see what's there. And when you're looking at what could be very old features, that's what you have to do because signatures at the surface become degraded over time."

Apollo 15 Commander David R. Scott, a visiting professor in the Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences at Brown, explored the Hadley-Apennine region at the edge of the Imbrium basin in 1971. "Orbiting the Moon following our surface exploration, it was very clear that Oceanus Procellarum differed in many ways from the circular maria in terms of its volcanic and tectonic activity," said Scott, who was not involved in this latest research. "After so many years of puzzling over this, GRAIL has now provided the data to show why it is so distinctly different."

Head said the results from this study show the remarkable extent to which internal processes can alter the surface of a planetary body. The data generated here will be helpful in understanding the evolution of other planets and moons, and aid in the continuing exploration of our own Moon.

INFORMATION:

Origin of moon's 'ocean of storms' revealed

2014-10-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers develop novel gene/cell therapy approach for lung disease

2014-10-01

CINCINNATI – Researchers developed a new type of cell transplantation to treat mice mimicking a rare lung disease that one day could be used to treat this and other human lung diseases caused by dysfunctional immune cells.

Scientists at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center report their findings in a study posted online Oct. 1 by Nature. In the study, the authors used macrophages, a type of immune cell that helps collect and remove used molecules and cell debris from the body.

They transplanted either normal or gene-corrected macrophages into the respiratory ...

New frontier in error-correcting codes

2014-10-01

CAMBRIDGE, Mass--Error-correcting codes are one of the glories of the information age: They're what guarantee the flawless transmission of digital information over the airwaves or through copper wire, even in the presence of the corrupting influences that engineers call "noise."

But classical error-correcting codes work best with large chunks of data: The bigger the chunk, the higher the rate at which it can be transmitted error-free. In the Internet age, however, distributed computing is becoming more and more common, with devices repeatedly exchanging small chunks of ...

Coral reef winners and losers

2014-10-01

Contrary to the popular research-based assumption that the world's coral reefs are doomed, a new longitudinal study from UC Santa Barbara's National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS) paints a brighter picture of how corals may fare in the future.

An NCEAS working group reports that there will be winners and losers among coral species facing increasing natural and human-caused stressors. However, its experts demonstrate that a subset of the present coral fauna will likely populate the world's oceans as water temperatures continue to rise. The findings ...

Proving 'group selection'

2014-10-01

PITTSBURGH—The notion of "group selection"—that members of social species exhibit individual behavioral traits that render a population more or less fit for survival—has been bandied about in evolutionary biology since Darwin. The essence of the argument against the theory is that it's a "fuzzy" concept without the precision of gene-based selection.

Jonathan Pruitt, assistant professor of behavioral ecology in the University of Pittsburgh's Department of Biological Sciences within the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, has published a paper today in the ...

New study provides key to identifying spiders in international cargo

2014-10-01

Spiders found in international cargo brought into North America are sometimes submitted to arachnologists for identification. Often, these spiders are presumed to be of medical importance because of their size or similarity to spiders that are known to be venomous.

In 2006, after witnessing multiple episodes where harmless spiders were mistaken for toxic ones, Dr. Richard Vetter, an arachnologist at the University of California, asked other arachnologists to provide data on specimens they found in international cargo that had been submitted to them for identification. ...

Scientists aim to give botox a safer facelift

2014-10-01

New insights into botulinum neurotoxins and their interactions with cells are moving scientists ever closer to safer forms of Botox and a better understanding of the dangerous disease known as botulism. By comparing all known structures of botulinum neurotoxins, researchers writing in the Cell Press journal Trends in Biochemical Sciences on October 1st suggest new ways to improve the safety and efficacy of Botox injections.

"If we know from high-resolution structures how botulinum neurotoxins interact with their receptors, we can design inhibitors or specific antibodies ...

Journal supplement examines innovative strategies for healthy aging

2014-10-01

WASHINGTON— The Society for Public Health Education (SOPHE) proudly announces the publication of a Health Education & Behavior (HE&B) supplement devoted to the latest research and practice to promote healthy aging. The October 2014 supplement, "Fostering Engagement and Independence: Opportunities and Challenges for an Aging Society," contains a dozen peer-reviewed articles on innovative behavioral and psycho-social approaches to improve the health of the nation's fastest growing cohort - older adults.

Together the articles describe promising advances in research directed ...

Hide and seek: Sterile neutrinos remain elusive

2014-10-01

BEIJING; BERKELEY, CA; and UPTON, NY - The Daya Bay Collaboration, an international group of scientists studying the subtle transformations of subatomic particles called neutrinos, is publishing its first results on the search for a so-called sterile neutrino, a possible new type of neutrino beyond the three known neutrino "flavors," or types. The existence of this elusive particle, if proven, would have a profound impact on our understanding of the universe, and could impact the design of future neutrino experiments. The new results, appearing in the journal Physical Review ...

New approach can predict impact of climate change on species that can't get out of the way

2014-10-01

CUMBERLAND, MD (October 1, 2014)--When scientists talk about the consequences of climate change, it can mean more than how we human beings will be impacted by higher temperatures, rising seas and serious storms. Plants and trees are also feeling the change, but they can't move out of the way. Researchers at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science and University of Vermont have developed a new tool to overcome a major challenge of predicting how organisms may respond to climate change.

"When climate changes, organisms have three choices: migrate, adapt, ...

Treatment of substance abuse can lessen risk of future violence in mentally ill

2014-10-01

BUFFALO, N.Y. — If a person is dually diagnosed with a severe mental illness and a substance abuse problem, are improvements in their mental health or in their substance abuse most likely to reduce the risk of future violence?

Although some may believe that improving symptoms of mental illness is more likely to lessen the risk for future episodes of violence, a new study from the University at Buffalo Research Institute on Addictions (RIA) suggests that reducing substance abuse has a greater influence in reducing violent acts by patients with severe mental illness. ...