(Press-News.org) The more curious we are about a topic, the easier it is to learn information about that topic. New research publishing online October 2 in the Cell Press journal Neuron provides insights into what happens in our brains when curiosity is piqued. The findings could help scientists find ways to enhance overall learning and memory in both healthy individuals and those with neurological conditions.

"Our findings potentially have far-reaching implications for the public because they reveal insights into how a form of intrinsic motivation—curiosity—affects memory. These findings suggest ways to enhance learning in the classroom and other settings," says lead author Dr. Matthias Gruber, of University of California at Davis.

For the study, participants rated their curiosity to learn the answers to a series of trivia questions. When they were later presented with a selected trivia question, there was a 14 second delay before the answer was provided, during which time the participants were shown a picture of a neutral, unrelated face. Afterwards, participants performed a surprise recognition memory test for the faces that were presented, followed by a memory test for the answers to the trivia questions. During certain parts of the study, participants had their brains scanned via functional magnetic resonance imaging.

The study revealed three major findings. First, as expected, when people were highly curious to find out the answer to a question, they were better at learning that information. More surprising, however, was that once their curiosity was aroused, they showed better learning of entirely unrelated information (face recognition) that they encountered but were not necessarily curious about. People were also better able to retain the information learned during a curious state across a 24-hour delay. "Curiosity may put the brain in a state that allows it to learn and retain any kind of information, like a vortex that sucks in what you are motivated to learn, and also everything around it," explains Dr. Gruber.

Second, the investigators found that when curiosity is stimulated, there is increased activity in the brain circuit related to reward. "We showed that intrinsic motivation actually recruits the very same brain areas that are heavily involved in tangible, extrinsic motivation," says Dr. Gruber. This reward circuit relies on dopamine, a chemical messenger that relays messages between neurons.

Third, the team discovered that when curiosity motivated learning, there was increased activity in the hippocampus, a brain region that is important for forming new memories, as well as increased interactions between the hippocampus and the reward circuit. "So curiosity recruits the reward system, and interactions between the reward system and the hippocampus seem to put the brain in a state in which you are more likely to learn and retain information, even if that information is not of particular interest or importance," explains principal investigator Dr. Charan Ranganath, also of UC Davis.

The findings could have implications for medicine and beyond. For example, the brain circuits that rely on dopamine tend to decline in function as people get older, or sooner in people with neurological conditions. Understanding the relationship between motivation and memory could therefore stimulate new efforts to improve memory in the healthy elderly and to develop new approaches for treating patients with disorders that affect memory. And in the classroom or workplace, learning what might be considered boring material could be enhanced if teachers or managers are able to harness the power of students' and workers' curiosity about something they are naturally motivated to learn.

INFORMATION:

Neuron, Gruber et al.: "States of curiosity modulate hippocampus-dependent learning via the dopaminergic circuit."

How curiosity changes the brain to enhance learning

2014-10-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Stopping liver cancer in its tracks

2014-10-02

This release is available in Japanese.

A University of Tokyo research group has discovered that AIM (Apoptosis Inhibitor of Macrophage), a protein that plays a preventive role in obesity progression, can also prevent tumor development in mice liver cells. This discovery may lead to a therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer and the third most common cause of cancer deaths.

Professor Toru Miyazaki's group at the Laboratory of Molecular Biomedicine from Pathogenesis, in the Faculty of Medicine has shown that AIM (also known ...

Ancient protein-making enzyme moonlights as DNA protector

2014-10-02

LA JOLLA, CA—October 2, 2014—Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have found that an enzyme best known for its fundamental role in building proteins has a second major function: to protect DNA during times of cellular stress.

The finding is remarkable on a basic science level but also points the way to possible therapeutic applications. Strategies that enhance the DNA-protection function of the enzyme, TyrRS, could help protect people from radiation injuries as well as from hereditary defects in DNA repair systems.

"We overexpressed TyrRS in zebrafish ...

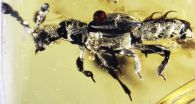

52-million-year-old amber preserves 'ant-loving' beetle

2014-10-02

Scientists have uncovered the fossil of a 52-million-year old beetle that likely was able to live alongside ants—preying on their eggs and usurping resources—within the comfort of their nest. The fossil, encased in a piece of amber from India, is the oldest-known example of this kind of social parasitism, known as "myrmecophily." Published today in the journal Current Biology, the research also shows that the diversification of these stealth beetles, which infiltrate ant nests around the world today, correlates with the ecological rise of modern ants.

"Although ants ...

Counting the seconds for immunological tolerance

2014-10-02

Our immune system must distinguish between self and foreign and in order to fight infections without damaging the body's own cells at the same time. The immune system is loyal to cells in the body, but how this works is not fully understood. Researchers in the Departments of Biomedicine and Nephrology at the University Hospital and the University of Basel have discovered that the immune system uses a molecular biological clock to target intolerant T cells during their maturation process. These recent findings have been reported in the scientific journal Cell.

A functioning ...

DNA 'bias' may keep some diseases in circulation, Penn biologists show

2014-10-02

It's an early lesson in genetics: we get half our DNA from Mom, half from Dad.

But that straightforward explanation does not account for a process that sometimes occurs when cells divide. Called gene conversion, the copy of a gene from Mom can replace the one from Dad, or vice versa, making the two copies identical.

In a new study published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, University of Pennsylvania researchers Joseph Lachance and Sarah A. Tishkoff investigated this process in the context of the evolution of human populations. They found that a bias toward ...

Study indicates possible new way to treat endometrial, colon cancers

2014-10-02

Scientists love acronyms.

In the quest to solve cancer's mysteries, they come in handy when describing tongue-twisting processes and pathways that somehow allow tumors to form and thrive. Two examples are ERK (extracellular-signal-related kinase) and JNK (c-June N-Terminal Kinase), enzymes that may offer unexpected solutions for treating some endometrial and colon cancers.

A study led by Gordon Mills, M.D., Ph.D., professor and chair of Systems Biology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center with Lydia Cheung, Ph.D. as the first author, points to cellular ...

Study gauges humor by age

2014-10-02

Television sitcoms in which characters make jokes at someone else's expense are no laughing matter for older adults, according to a University of Akron researcher.

Jennifer Tehan Stanley, an assistant professor of psychology, studied how young, middle-aged and older adults reacted to so-called "aggressive humor"—the kind that is a staple on shows like The Office.

By showing clips from The Office and other sitcoms (Golden Girls, Mr. Bean, Curb Your Enthusiasm) to adults of varying ages, she and colleagues at two other universities found that young and middle-aged adults ...

Strong working memory puts brakes on problematic drug use

2014-10-02

AUDIO:

Atika Khurana, assistant professor in the University of Oregon's Department of Counseling Psychology and Human Services, provides a short summary and the implications of a study that looked at the...

Click here for more information.

EUGENE, Ore. -- Oct. 2, 2014 -- Adolescents with strong working memory are better equipped to escape early drug experimentation without progressing into substance abuse issues, says a University of Oregon researcher.

Most important in the picture ...

Sense of invalidation uniquely risky for troubled teens

2014-10-02

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Among the negative feelings that can plague a teen's psyche is a perception of "invalidation," or a lack of acceptance. A new study by Brown University and Butler Hospital researchers suggests that independent of other known risk factors, measuring teens' sense of invalidation by family members or peers can help predict whether they will try to harm themselves or even attempt suicide.

In some cases, as with peers, that sense of invalidation could come from being bullied, but it could also be more subtle. In the case of family, for ...

Socioeconomic factors, fashion trends linked to increase in melanoma

2014-10-02

NEW YORK, NY - A century's worth of cultural and historical forces have contributed to the rise in the incidence of melanoma, including changes in fashion and clothing design, according to an intriguing, retrospective research study conducted by investigators in the Ronald O. Perelman Department of Dermatology at NYU Langone Medical Center.

Their findings are the subject of a report, "More Skin, More Sun, More Tan, More Melanoma," in the October 6, 2014 issue of the American Journal of Public Health.

The authors surmised that early diagnosis and improved reporting ...