(Press-News.org) VIDEO:

Princeton University researchers first deposited iron atoms onto a lead surface to create an atomically thin wire. They then used a scanning-tunneling microscope to create a magnetic field and to...

Click here for more information.

Princeton University scientists have observed an exotic particle that behaves simultaneously like matter and antimatter, a feat of math and engineering that could yield powerful computers based on quantum mechanics.

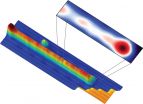

Using a two-story-tall microscope floating in an ultralow-vibration lab at Princeton's Jadwin Hall, the scientists captured a glowing image of a particle known as a "Majorana fermion" perched at the end of an atomically thin wire — just where it had been predicted to be after decades of study and calculation dating back to the 1930s.

"This is the most direct way of looking for the Majorana fermion as it is expected to emerge at the edge of certain materials," said Ali Yazdani, a professor of physics who led the research team. "If you want to find this particle within a material you have to use such a microscope, which allows you to see where it actually is."

The hunt for the Majorana fermion began in the earliest days of quantum theory when physicists first realized that their equations implied the existence of "antimatter" counterparts to commonly known particles such as electrons. In 1937, Italian physicist Ettore Majorana predicted that a single, stable particle could be both matter and antimatter. Although many forms of antimatter have since been observed, the Majorana combination remained elusive.

In addition to its implications for fundamental physics, the finding offers scientists a potentially major advance in the pursuit of quantum computing. In quantum computing, electrons are coaxed into representing not only the ones and zeroes of conventional computers but also a strange quantum state that is both a one and a zero. This anomalous property, called quantum superposition, offers vast opportunities for solving previously incalculable systems, but is notoriously prone to collapsing into conventional behavior due to interactions with nearby material.

Despite combining qualities usually thought to annihilate each other — matter and antimatter — the Majorana fermion is surprisingly stable; rather than being destructive, the conflicting properties render the particle neutral so that it interacts very weakly with its environment. This aloofness has spurred scientists to search for ways to engineer the Majorana into materials, which could provide a much more stable way of encoding quantum information, and thus a new basis for quantum computing.

A team led by Yazdani and including colleagues at Princeton and at the University of Texas-Austin published their results in the Oct. 2 issue of the journal Science.

Yazdani noted that the observation of the Majorana fermion bound within a material is different for physicists than the much publicized discovery of particles, such as the Higgs boson, in a vacuum in giant accelerators. In such experiments, scientists collide particles at high speeds, producing a shower of free and ephemeral components. In materials, by contrast, the existence of a particle depends on — or emerges from — the collective properties of atoms and forces surrounding it.

By controlling these interactions, the researchers said, their Majoranas appeared "clean and removed from any spurious particles," which would be unavoidable in high-energy accelerator experiments. "This is more exciting and can actually be practically beneficial," Yazdani said, "because it allows scientists to manipulate exotic particles for potential applications, such as quantum computing."

In addition to their potential practical uses, the pursuit of Majoranas has broad implications for other areas of physics. Scientists believe, for example, that another sub-atomic particle called neutrinos, which also interact very weakly and are very hard to detect, could be a type of Majorana — a neutrino and anti-neutrino being the same particle. In addition, scientists regard Majoranas as possible candidates for dark matter, the mysterious substance that is thought to account for most matter in the universe, but which has not been directly observed because it also does not directly interact with other particles.

Despite the scientific interest, there was little progress in finding the particle until 2001 when the physicist Alexei Kitaev (now a professor at the University of California-Santa Barbara) predicted that, under the correct conditions, a Majorana fermion would appear at each end of a superconducting wire. Superconductivity is the phenomenon when a material can carry electricity without any resistance. In Kitaev's prediction, inducing some types of superconductivity would cause the formation of Majoranas. These emergent particles are stable and do not annihilate each other (unless the wire is too short) because they are spatially separated. Importantly, Kitaev also outlined how such a particle could be harnessed as a qubit, the basis of a quantum computer, which added significant impetus to the search.

In 2012, a team of researchers at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands may have caught a glimpse of Majorana fermions in an experiment that induced superconductivity in a semiconductor known as indium antemonide. They reported very strong evidence for the electrical signal characteristic of a neutral Majorana in nanoscale wires made of these materials.

Scientists, however, have argued that other phenomena could produce the same signal, and Yazdani and his team sought to find more definitive observation of Majorana fermions by capturing an image of them. In 2013, Yazdani and Andrei Bernevig, an associate professor of physics, teamed up to propose a new approach for how the Majorana particle could occur in materials that combine magnetism and superconductivity. They also proposed that such a particle could be directly observed using a device called a scanning-tunneling microscope.

Yazdani and Bernevig received funding to carry out their proposed experiments through the Princeton Center for Complex Materials, an interdisciplinary center on campus funded by the National Science Foundation. Promising results from that work allowed them to partner with the Texas team and win a $3 million grant from the Office of Naval Research under a program called the Majorana Basic Research Challenge.

The setup they created starts with an ultrapure crystal of lead, whose atoms naturally line up in alternating rows that leave atomically thin ridges on the crystal's surface. The researchers then deposited pure iron into one of these ridges to create a wire that is just one atom wide and about three atoms thick. Considering its narrow width, this wire is very long — if it were a pencil it would be five feet from tip to eraser.

The researchers then placed the lead and the embedded iron wire under the scanning-tunneling microscope and cooled the system to -272 degrees Celsius, just a degree above absolute zero. After about two years of painstaking work, they confirmed that superconductivity in the iron wire matched the conditions required for Majorana fermion to be created in their material.

Ultimately, the microscope was also able to detect an electrically neutral signal at the ends of the wires, similar to those seen in the Delft experiment. However, the setup also allowed the researchers to directly visualize how the signal changes along the wire, essentially mapping the quantum probability of finding the Majorana fermion along the wire and pinpointing that it appears at the ends of the wire.

"It shows that this signal lives only at the edge," Yazdani said. "That is the key signature. If you don't have that, then this signal can exist for many other reasons."

Yazdani noted that although the experimental setup used to measure and demonstrate the existence of Majorana particle is very complex, the new approach does not use exotic materials and is straightforward for other scientists to reproduce and use.

"What's very exciting is that it is very simple: it is lead and iron," he said.

In fact, in the course of their experiments the researchers found that their approach is even easier to use than they expected. While they set out to fine-tune the properties of their materials to exact specifications, they found that their system is almost guaranteed to have Majorana fermions, as long as some general features of magnetism and superconductivity are in place. Calculations performed by the Austin team led by Professor Allan MacDonald have confirmed this picture.

"The details turned out to be not that important," Yazdani said.

Bernevig added, "As long as you have a strong magnetic material — like iron but it could be other magnets — in which electrons are magnetically polarized (or electrons feel a very strong magnetic field), the possible range of parameters in which Majoranas appear increases dramatically."

In previous proposals, the appearance of Majoranas would only happen under a narrow range of conditions. Typically, it is hard to have superconductivity and magnetism in the same material — magnetic fields usually kill superconductivity. But in the Princeton team's method, the magnetic field is present only where it is needed, on the wire, so superconductivity creeps in from the underlying lead unimpeded.

"Once you have that, all you need are some relativistic effects that are easy to induce at the surface of a heavy element like lead, and the Majoranas will appear," Bernevig said. "We expect many more materials will produce these elusive particles."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Yazdani, Bernevig and MacDonald, authors of the work are graduate student Ilya Drozdov and postdoctoral researchers Stevan Nadj-Perge, Jian Li, Sangjun Jeon and Jungpil Seo of Princeton, and Hua Chen of the University of Texas.

Princeton scientists observe elusive particle that is its own antiparticle

2014-10-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

HIV pandemic's origins located

2014-10-02

The HIV pandemic with us today is almost certain to have begun its global spread from Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), according to a new study.

An international team, led by Oxford University and University of Leuven scientists, has reconstructed the genetic history of the HIV-1 group M pandemic, the event that saw HIV spread across the African continent and around the world, and concluded that it originated in Kinshasa. The team's analysis suggests that the common ancestor of group M is highly likely to have emerged in Kinshasa around ...

New map exposes previously unseen details of seafloor

2014-10-02

Accessing two previously untapped streams of satellite data, scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego and their colleagues have created a new map of the world's seafloor, creating a much more vivid picture of the structures that make up the deepest, least-explored parts of the ocean. Thousands of previously uncharted mountains rising from the seafloor and new clues about the formation of the continents have emerged through the new map, which is twice as accurate as the previous version produced nearly 20 years ago.

Developed using a scientific ...

New study suggests humans to blame for plummeting numbers of cheetahs

2014-10-02

A new study led by Queen's University Belfast into how cheetahs burn energy suggests that human activity, rather than larger predators, may force them to expend more energy and thus be the major cause of their decline.

Wild cheetahs are down to under 10,000 from 100,000 a century ago with conventional wisdom blaming bigger predators for monopolising available food as their habitat becomes restricted. The traditional thinking has been that cheetahs no longer have sufficient access to prey to fuel their enormous energy output when engaging in super-fast chases.

But, ...

New approach to boosting biofuel production

2014-10-02

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Yeast are commonly used to transform corn and other plant materials into biofuels such as ethanol. However, large concentrations of ethanol can be toxic to yeast, which has limited the production capacity of many yeast strains used in industry.

"Toxicity is probably the single most important problem in cost-effective biofuels production," says Gregory Stephanopoulos, the Willard Henry Dow Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT.

Now Stephanopoulos and colleagues at MIT and the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research have identified a new way to ...

Falling asleep: Revealing the point of transition

2014-10-02

How can we tell when someone has fallen asleep? To answer this question, scientists at Massachusetts General Hospital have developed a new statistical method and behavioural task to track the dynamic process of falling asleep.

Dr Michael Prerau, Dr Patrick Purdon, and their colleagues used the evolution of brain activity, behaviour, and other physiological signals during the sleep onset process to automatically track the continuous changes in wakefulness experienced as a subject falls asleep.

The study, publishing today in PLOS Computational Biology, suggests that it ...

Researchers identify new pathway linking the brain to high blood pressure

2014-10-02

VIDEO:

Dr. Frans Leenen, from the University of Ottawa Heart Institute, discusses the importance of these new findings.

Click here for more information.

Ottawa, ON and Baltimore, MD, October 2, 2014—New research by scientists at the Ottawa Heart Institute and the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UM SOM) has uncovered a new pathway by which the brain uses an unusual steroid to control blood pressure. The study, which also suggests new approaches for treating high blood ...

York academics reveal new findings about insect diversification

2014-10-02

Biologists from the University of York have compiled two new datasets on insect evolution, revealing that metamorphosing insects diversify more quickly than other insects and are therefore the biggest contributors to the evolution of insect diversity.

Both funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), the first dataset is a complete fossil catalogue showing timescales of origination and extinction of different families of insects. Working with the Natural History Museum and National Museums Scotland, former PhD student Dr David Nicholson collated a database ...

A closer look at the perfect fluid

2014-10-02

By combining data from two high-energy accelerators, nuclear scientists have refined the measurement of a remarkable property of exotic matter known as quark-gluon plasma. The findings reveal new aspects of the ultra-hot, "perfect fluid" that give clues to the state of the young universe just microseconds after the big bang.

The multi-institutional team known as the JET Collaboration, led by researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (Berkeley Lab), published their results in a recent issue of Physical Review C. The JET Collaboration ...

Supreme delay: Why the nation's highest court puts off big decisions until the last moment

2014-10-02

As the Supreme Court of the United States begins its fall 2014 session this month, it faces decisions on several "blockbuster" cases, including freedom of speech, religious freedoms in prison, pregnancy discrimination and a possible decision on gay marriage.

Just don't expect any of these decisions until next June, just before the court's session ends.

New research from the Washington University in St. Louis School of Law finds big, or "blockbuster," cases are disproportionately decided at the end of June, just before the court's summer recess.

"We knew that more than ...

Washington University review identifies factors associated with childhood brain tumors

2014-10-02

Older parents, birth defects, maternal nutrition and childhood exposure to CT scans and pesticides are increasingly being associated with brain tumors in children, according to new research from the Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis.

Brain and central nervous system tumors are the second leading cause of cancer death in children.

A team of researchers, led by Kimberly Johnson, PhD, assistant professor of social work at the Brown School, a member of the Institute for Public Health and a research member of Siteman Cancer Center, examined studies published ...