(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. –- No single "one-size-fits-all" model can explain how biodiversity hotspots come to be, finds a study of more than 700 species of reptiles and amphibians on the African island of Madagascar.

By analyzing the geographic distribution of Madagascar's lizards, snakes, frogs and tortoises, an international team of researchers has found that each group responded differently to environmental fluctuations on the island over time.

The results are important because they suggest that climate change and land use in Madagascar will have varying effects on different species, said Jason Brown of the City College of New York.

"It means that there won't be a uniform decline of species -- some species will do better, and others will do worse," said Brown, a co-author on the study appearing online in the journal Nature Communications.

The study is part of a larger body of research aimed at identifying the climate, geology and other features of the environment that help bring new species of plants and animals into being in an area, and then sustain once they're there.

Located 300 miles off the southeast coast of Africa, the island of Madagascar is a treasure trove of unusual animals, about 90 percent of which are found nowhere else on Earth. Cut off from the African and Indian mainlands for more than 80 million years, the animals of Madagascar have evolved into a unique menagerie of creatures, including more than 700 species of reptiles and amphibians -- snakes, geckos, iguanas, chameleons, skinks, frogs, turtles and tortoises.

Visitors to the island may come across neon green geckos that can grow up to a foot in length, and tiny tree frogs that secrete toxic chemicals from their skin and come in combinations of black and iridescent blue, orange, yellow and green. They'll also find about half of the world's chameleons -- lizards famous for their bulging eyes, sticky high-speed tongues and ability to change color.

Researchers have long sought to understand how Madagascar -- a country that makes up less than 0.5 percent of the Earth's land surface area -- gave rise to so many unusual species.

Previous studies have linked the distribution of species to various factors, such as steep slopes that fuel diversity by creating a range of habitats in a small area. But few studies have integrated all of these variables into a single model to examine the relative influence of multiple factors at once, Brown said.

He and Duke University biologist Anne Yoder and colleagues developed a model that combines the modern distributions of 325 species of amphibians and 420 species of reptiles that live in Madagascar today with historical and present-day estimates of topography, rainfall and other variables across the island.

From steep tropical rainforests to flat, desert-like regions, the researchers analyzed three measures of biodiversity: the number of species, the proportion of unique species and the similarity of species composition from one site to another.

"Not surprisingly, we found that different groups of species have diversified for different reasons," Yoder said.

For example, changes in elevation -- due to the mountains, rivers and other features that shape the land -- best predicted which parts of the island had high proportions of unique tree frog species. But the biggest influence on why some areas had higher proportions of unique leaf chameleons was climate stability through time.

"What governs the distribution of, say, a particular group of frogs isn't the same as what governs the distribution of a particular group of snakes," Brown said. "A one-size-fits-all model doesn't exist."

Understanding how species distributions responded to environmental fluctuations in the past may help scientists predict which groups are most vulnerable to global warming and deforestation in the future, or which factors pose the biggest threat.

Other studies have found that some of Madagascar's reptiles and amphibians are already moving up to higher elevations due to climate change, and roughly 40 percent of the country's reptile species are threatened with extinction due to logging and farming in their forest habitats.

The difficulty of using this model to predict species' responses is that the environmental fluctuations the researchers examined occurred over tens of thousands of years, whereas the changes in climate and land use that Madagascar is currently experiencing are taking place over a matter of decades, said Brown, who was a postdoctoral research associate at Duke at the time of the research.

Making accurate predictions about the threat of future extinction requires determining the timescales at which current environmental changes pose a threat.

"One of the lessons learned is that when trying to assess the impacts of future climate change on species distribution and survival, we have to deal in specifics rather than generalities, since each group of animals experiences its environment in a way that is unique to its life history and other biological characteristics," Yoder said.

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the study were Alison Cameron of Queen's University in Belfast and Miguel Vences of the Technical University of Braunschweig, Germany. This work was supported by Duke University, the Volkswagen Foundation and the National Science Foundation.

Citation: "A necessarily complex model to explain the biogeography of the amphibians and reptiles of Madagascar," Brown, Jl, et al. Nature Communications, October 2014. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms6046

NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Tropical Cyclone Hudhud on Oct. 10 as it reached hurricane-force.

The Atmospheric Infrared Sounder or AIRS instrument that flies aboard NASA's Aqua satellite read temperatures of thunderstorm cloudtops that make up Tropical Cyclone Hudhud when it passed overhead on Oct. 9 at 19:53 UTC (3:53 p.m. EDT). The data showed the coldest cloud top temperatures were in thunderstorms circling a developing eye. Cloud top temperatures were as cold as -63F/-53C, which have the potential for dropping heavy rainfall.

Hudhud's maximum sustained winds ...

Small cues that display a user's transaction history may help a website feel almost as interactive as chatting with an online customer service agent, paving the way for more cost-effective websites, according to researchers.

"One of the challenges with online interactivity is trying to imbue the site with a sense of contingency -- the back-and-forth feel of a real conversation," said S. Shyam Sundar, Distinguished Professor of Communications and co-director of the Media Effects Research Laboratory. "What we found is that providing some information about a user's interaction ...

A new study led by a Canadian marine zoologist reviews the world list of specialist driftwood talitrids, which so far comprises a total of 7 representatives, including two newly described species. These tiny animals with peculiar habits all live in and feed on decomposing marine driftwood. Dispersed across distant oceanic islands they use floating driftwood to hitch a ride to their destination. The study was published in the open access journal Zoosystematics and Evolution.

Tourists are familiar with talitrids as sandhoppers, found in burrows on sand beaches, or shorehoppers, ...

New clinical research from UC San Francisco shows that 341 HIV-infected men who reported using stimulants such as methamphetamine or cocaine derived life-saving benefits from being on antiretroviral therapy that were comparable to those of HIV-infected men who do not use stimulants.

That said, those who reported using stimulants at more than half of at least two study visits did have modestly increased chances of progressing to AIDS or dying after starting antiretroviral therapy compared to non-users. The data was collected between 1996 and 2012.

"Patients with HIV ...

PHILADELPHIA –The pneumococcal vaccine recommended for young children not only prevents illness and death, but also has dramatically reduced severe antibiotic-resistant infections, suggests nationwide research being presented at IDWeek 2014™. Pneumococcal infection – which can cause everything from ear infections to pneumonia and meningitis – is the most common vaccine-preventable bacterial cause of death.

The 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), first available in 2010 (replacing 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, PCV7), reduced the ...

PHILADELPHIA – Old-school face-to-face social networking is a more effective way to identify people with HIV than the traditional referral method, suggests research being presented at IDWeek 2014™. The study shows that social networking strategies (SNS) – enlisting people in high-risk groups to recruit their peers to get tested – is more efficient and targeted than traditional testing and referral programs, resulting in 2-1/2 times more positive test results.

As many as 20 percent of HIV-positive people are unaware of being infected with the virus, ...

The experiments were carried out on endofullerenes, molecules of C60 into which smaller molecules of Hydrogen (H2) had been inserted. The results, published in Physical Review Letters, represent the first known example of a quantum selection rule found in a molecule.

Similar techniques were also used by the same team to uncover an exciting new symmetry-breaking interaction of water molecules with C60 cages, published last month in Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics.

The use of fullerenes such as C60 to trap smaller molecules, using cutting-edge molecular surgery techniques, ...

This news release is available in German.

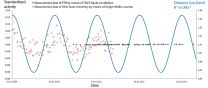

The distance between the Earth and the Sun has no influence on the decay rate of radioactive chlorine. You could ask: "And why should it anyway?", because it is well known that the decay of radionuclides is as reliable as a Swiss clock. Recently, US-American scientists, however, attracted attention when they postulated that the decay rate depends on the flow of solar neutrinos and, thus, also on the distance from the Earth to the Sun. Their assumption was based, among other things, on older measurement data of the Physikalisch-Technische ...

WASHINGTON, DC – OCTOBER 10, 2014 - Mineral coatings on sand particles actually encourage microbial activity in the rapid sand filters that are used to treat groundwater for drinking, according to a paper published ahead of print in Applied and Environmental Microbiology. These findings resoundingly refute, for the first time, the conventional wisdom that the mineral deposits interfere with microbial colonization of the sand particles.

"We find an overwhelmingly positive effect of mineral deposits on microbial activity and density," says corresponding author Barth ...

A study on the global burden of venous thromboembolism—when a dangerous clot forms in a blood vessel—found that annual incidences range from 0.75 to 2.69 per 1,000 individuals in the population. The incidence increased to between 2 and 7 per 1,000 among those 70 years of age or more.

"Venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients was responsible for more years lost due to ill-health than hospital-acquired pneumonia, catheter-related blood stream infections, and side effects from drugs," said Dr. Gary Raskob, co-author of the Journal of Thrombosis & Haemostasis ...