(Press-News.org) Extreme adaptations of species often cause such significant changes that their evolutionary history is difficult to reconstruct. Zoologists at the University of Basel in Switzerland have now discovered a new parasite species that represents the missing link between fungi and an extreme group of parasites. Researches are now able to understand for the first time the evolution of these parasites, causing disease in humans and animals. The study has been published in the latest issue of the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Parasites use their hosts to simplify their own lives. In order to do so, they evolved features that are so extreme that it is often impossible to compare them to other species. The evolution of these extreme adaptations is often impossible to reconstruct. The research group lead by Prof. Dieter Ebert from the Department of Environmental Science at the University of Basel has now discovered the missing link that explains how this large group of extreme parasites, the microsporidia, has evolved. The team was supported in their efforts by scientists from Sweden and the U.S.

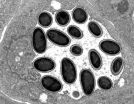

Microsporidia are a large group of extreme parasites that invade humans and animals and cost great damage for health care systems and in agriculture; over 1,200 species are known. They live inside their host's cells and have highly specialized features: They are only able to reproduce inside the host's cells, they have the smallest known genome of all organisms with a cell nucleus (eukaryotes) and they posses no mitochondria of their own (the cell's power plant). In addition, they developed a specialized infection apparatus, the polar tube, which they use to insert themselves into the cells of their host. Due to their phenomenal high molecular evolution rate, genome analysis has so far been rather unsuccessful: Their great genomic divergence from all other known organisms further complicates the study of their evolutionary lineage.

Between fungi and parasite

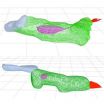

The team of zoologists lead by Prof. Dieter Ebert has been studying the evolution of microsporidia for years. When they discovered a new parasite in water fleas a couple of years ago, they classified this undescribed species as a microsporidium, mostly because it possessed the unique harpoon-like infection apparatus (the polar-tube), one of the hallmarks of microsporidia. The analysis of the entire genome had several surprises in store for them: The genome resembles more that of a fungi than a microsporidium and, in addition, also has a mitochondrial genome. The new species, now named Mitosporidium daphniae, thus represents the missing link between fungi and microsporidia.

With the help of scientists in Sweden and the U.S., the Basel researchers rewrote the evolutionary history of microsporidia. First, they showed that the new species derives from the ancestors of all known microsporidians and further, that the microsporidians derive from the most ancient fungi; thus its exact place in the tree of life has finally been found. Further research confirms that the new species does in fact have a microsporidic, intracellular and parasitic lifestyle, but that its genome is rather atypical for a microsporidium. It resembles much more the genome of their fungal ancestors.

Genome modifications

The scientists thus conclude that the microsporidia adopted intracellular parasitism first and only later changed their genome significantly. These genetic adaptations include the loss of mitochondria, as well as extreme metabolic and genomic simplification. "Our results are not only a milestone for the research on microsporidia, but they are also of great interest to the study of parasite-specific adaptations in evolution in general", explains Ebert the findings.

INFORMATION:

Original source

Haag, K.L., James, T.Y., Pombert, J.-F., Larsson, R., Schaer, T.M.M., Refardt, D. & Ebert, D. 2014.

Evolution of a morphological novelty occurred before genome compaction in a lineage of extreme parasites

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 13. Oktober 2014) http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1410442111

Swiss scientists explain evolution of extreme parasites

2014-10-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Spinal cord injury victims may benefit from stem cell transplantation studies

2014-10-14

Putnam Valley, NY. (Oct. 13, 2014) – Two studies recently published in Cell Transplantation reveal that cell transplantation may be an effective treatment for spinal cord injury (SCI), a major cause of disability and paralysis with no current restorative therapies.

Using laboratory rats modeled with SCI, researchers in Spain found in laboratory tests on cells harvested from rats - specifically ependymal progenitor cells (epSPCs), multipotent stem cells found in adult tissues surrounding the ependymal canal of the spinal cord - responded to a variety of compounds ...

Treating cancer: UI biologists find gene that could stop tumors in their tracks

2014-10-14

The dirt in your backyard may hold the key to isolating cancerous tumors and to potential new treatments for a host of cancers.

University of Iowa researchers have found a gene in a soil-dwelling amoeba that functions similarly to the main tumor-fighting gene found in humans, called PTEN.

When healthy, PTEN suppresses tumor growth in humans. But the gene is prone to mutate, allowing cancerous cells to multiply and form tumors. PTEN mutations are believed to be involved in 40 percent of breast cancer cases, up to 70 percent of prostate cancer cases, and nearly half of ...

How metastases develop in the liver

2014-10-14

This news release is available in German. In order to invade healthy tissue, tumor cells must leave the actual tumor and enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system. For this purpose, they use certain enzymes, proteases that break down the tissue surrounding the tumor, thus opening the way for tumor cells to reach blood or lymphatic vessels. To keep the proteases in check, the body produces inhibitors such as the protein TIMP-1, which thwart the proteases in their work.

But during development of metastases, the control function of this inhibitor appears not only to ...

Size of minority population impacts states' prison rates, Baker Institute researcher finds

2014-10-14

HOUSTON – (Oct. 13, 2014) – New research from Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy found that states with a large minority population tend to incarcerate more people.

According to lead author Katharine Neill, states with large African-American populations are more likely to have harsher incarceration practices, worse conditions of confinement and tougher policies toward juveniles compared with other states. She said these findings provide some support for long-standing arguments among sociology and criminal justice experts that the criminal ...

Uncertain reward more motivating than sure thing, study finds

2014-10-14

Recently, uncertainty has been getting a bad rap. Hundreds of articles have been printed over the last few years about how uncertainty brings negative effects to the markets and creates a drag on the economy at large. But a new study appearing in the February 2015 edition of the Journal of Consumer Research finds that uncertainty can be motivating.

In "The Motivating-Uncertainty Effect: Uncertainty Increases Resource Investment in the Process of Reward Pursuit," Professors Ayelet Fishbach and Christopher K. Hsee of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and ...

Inside the Milky Way

2014-10-14

Is matter falling into the massive black hole at the center of the Milky Way or being ejected from it? No one knows for sure, but a UC Santa Barbara astrophysicist is searching for an answer.

Carl Gwinn, a professor in UCSB's Department of Physics, and colleagues have analyzed images collected by the Russian spacecraft RadioAstron. Their findings appear in the current issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

RadioAstron was launched into orbit from Baikonur, Kazakhstan, in July 2011 with several missions, one of which was to investigate the scattering of pulsars ...

PTPRZ-MET fusion protein: A new target for personalized brain cancer treatment

2014-10-14

Researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have identified a new fusion protein found in approximately 15 percent of secondary glioblastomas or brain tumors. The finding offers new insights into the cause of this cancer and provides a therapeutic target for personalized oncologic care. The findings were published this month in the online edition of Genome Research.

Glioblastoma is the most common and deadliest form of brain cancer. The majority of these tumors – known as primary glioblastomas – occur in the elderly without evidence ...

Researchers say academia can learn from Hollywood

2014-10-14

HOUSTON, Oct. 13, 2014 – According to a pair of University of Houston (UH) professors and their Italian colleague, while science is increasingly moving in the direction of teamwork and interdisciplinary research, changes need to be made in academia to allow for a more collaborative model to flourish.

Professors Ioannis T. Pavlidis and Ioanna Semendeferi from UH and Alexander M. Petersen from the IMT Lucca Institute for Advanced Studies in Italy published a commentary in the October 2014 issue of Nature Physics, articulating policies that will harmonize academic ...

University of Tennessee study finds crocodiles are sophisticated hunters

2014-10-14

Recent studies have found that crocodiles and their relatives are highly intelligent animals capable of sophisticated behavior such as advanced parental care, complex communication and use of tools for hunting.

New University of Tennessee, Knoxville, research published in the journal Ethology Ecology and Evolution shows just how sophisticated their hunting techniques can be.

Vladimir Dinets, a research assistant professor in UT's Department of Psychology, has found that crocodiles work as a team to hunt their prey. His research tapped into the power of social media ...

Out-of-step cells spur muscle fibrosis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients

2014-10-14

AUDIO:

A study in The Journal of Cell Biology suggests that asynchronous regeneration of cells within muscle tissue leads to the development of fibrosis in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Listen...

Click here for more information.

Like a marching band falling out of step, muscle cells fail to perform in unison in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. A new study in The Journal of Cell Biology reveals how this breakdown leads to the proliferation of stiff fibrotic ...