(Press-News.org) WORCESTER, MA – An international group of scientists led by Gang Han, PhD, at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, has combined a new type of nanoparticle with an FDA-approved photodynamic therapy to effectively kill deep-set cancer cells in vivo with minimal damage to surrounding tissue and fewer side effects than chemotherapy. This promising new treatment strategy could expand the current use of photodynamic therapies to access deep-set cancer tumors.

"We are very excited at the potential for clinical practice using our enhanced red-emission nanoparticles combined with FDA-approved photodynamic drug therapy to kill malignant cells in deeper tumors," said Dr. Han, lead author of the study and assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular pharmacology at UMMS. "We have been able to do this with biocompatible low-power, deep-tissue-penetrating 980-nm near-infrared light."

In photodynamic therapy, also known as PDT, the patient is given a non-toxic light-sensitive drug, which is absorbed by all the body's cells, including the cancerous ones. Red laser lights specifically tuned to the drug molecules are then selectively turned on the tumor area. When the red light interacts with the photosensitive drug, it produces a highly reactive form of oxygen (singlet oxygen) that kills the malignant cancer cells while leaving most neighboring cells unharmed.

Because of the limited ability of the red light to penetrate tissue, however, current photodynamic therapies are only used for skin cancer or lesions in very shallow tissue. The ability to reach deeper set cancer cells could extend the use of photodynamic therapies.

In research published online by the journal ACS Nano of the American Chemical Society, Han and colleagues describe a novel strategy that makes use of a new class of upconverting nanoparticles (UCNPs), a billionth of a meter in size, which can act as a kind of relay station. These UCNPs are administered along with the photodynamic drug and convert deep penetrating near-infrared light into the visible red light that is needed in photodynamic therapies to activate the cancer-killing drug.

To achieve this light conversion, Han and colleagues engineered a UCNP to have better emissions in the red part of the spectrum by coating the nanoparticles with calcium fluoride and increasing the doping of the nanoparticles with ytterbium.

In their experiments, the researchers used the low-cost, FDA-approved photosensitizer drug aminolevulinic acid and combined it with the augmented red-emission UCNPs they had developed. Near-infrared light was then turned on the tumor location. Han and colleagues showed that the UCNPs successfully converted the near-infrared light into red light and activated the photodynamic drug at levels deeper than can be currently achieved with photodynamic therapy methods. Performed in both in vitro and with animal models, the combination therapy showed an improved destruction of the cancerous tumor using lower laser power.

Yong Zhang, PhD, chair professor of National University of Singapore and a leader in the development and application of upconversion nanoparticles, who was not involved in the study, said that by successfully engineering amplified red emissions in these nanoparticles, the research team has created the deepest-ever photodynamic therapy using an FDA-approved drug.

"This therapy has great promise as a noninvasive killer for malignant tumors that are beyond 1 cm in depth—breast cancer, lung cancer, and colon cancer, for example—without the side-effects of chemotherapy," Zhang said.

Han said, "This approach is an exciting new development for cancer treatment that is both effective and nontoxic, and it also opens up new opportunities for using the augmented red-emission nanoparticles in other photonic and biophotonic applications."

INFORMATION:

About the University of Massachusetts Medical School

The University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS), one of five campuses of the University system, comprises the School of Medicine, the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, the Graduate School of Nursing, a thriving research enterprise and an innovative public service initiative, Commonwealth Medicine. Its mission is to advance the health of the people of the commonwealth through pioneering education, research, public service and health care delivery with its clinical partner, UMass Memorial Health Care. In doing so, it has built a reputation as a world-class research institution and as a leader in primary care education. The Medical School attracts more than $240 million annually in research funding, placing it among the top 50 medical schools in the nation. In 2006, UMMS's Craig C. Mello, PhD, Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator and the Blais University Chair in Molecular Medicine, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, along with colleague Andrew Z. Fire, PhD, of Stanford University, for their discoveries related to RNA interference (RNAi). The 2013 opening of the Albert Sherman Center ushered in a new era of biomedical research and education on campus. Designed to maximize collaboration across fields, the Sherman Center is home to scientists pursuing novel research in emerging scientific fields with the goal of translating new discoveries into innovative therapies for human diseases.

Montréal, October 15, 2014 – An important scientific breakthrough by a team of IRCM researchers led by Michel Cayouette, PhD, is being published today by The Journal of Neuroscience. The Montréal scientists discovered that a protein found in the retina plays an essential role in the function and survival of light-sensing cells that are required for vision. These findings could have a significant impact on our understanding of retinal degenerative diseases that cause blindness.

The researchers studied a process called compartmentalization, which establishes ...

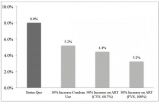

Do you believe in science? Your faith in science may actually make you more likely to trust information that appears scientific but really doesn't tell you much. According to a new Cornell Food and Brand Lab study, published in Public Understanding of Science, trivial elements such as graphs or formulas can lead consumers to believe products are more effective. "Anything that looks scientific can make information you read a lot more convincing," says the study's lead author Aner Tal, PhD, "The scientific halo of graphs, formulas, and other trivial elements that look scientific ...

During the 1930s, North America endured the Dust Bowl, a prolonged era of dryness that withered crops and dramatically altered where the population settled. Land-based precipitation records from the years leading up to the Dust Bowl are consistent with the telltale drying-out period associated with a persistent dry weather pattern, but they can't explain why the drought was so pronounced and long-lasting.

The mystery lies in the fact that land-based precipitation tells only part of the climate story. Building accurate computer reconstructions of historical global precipitation ...

Our mood can affect how we walk — slump-shouldered if we're sad, bouncing along if we're happy. Now researchers have shown it works the other way too — making people imitate a happy or sad way of walking actually affects their mood.

Subjects who were prompted to walk in a more depressed style, with less arm movement and their shoulders rolled forward, experienced worse moods than those who were induced to walk in a happier style, according to the study published in the Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry.

CIFAR Senior Fellow Nikolaus ...

Rochester, Minn. – The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM) offer a new guideline on how to determine what genetic tests may best diagnose a person's subtype of limb-girdle or distal muscular dystrophy. The guideline is published in the October 14, 2014, print issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the AAN.

Researchers reviewed all of the available studies on the muscular dystrophy, a group of genetic diseases in which muscle fibers are unusually susceptible to damage, as ...

COLUMBIA, Mo. – According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), many teens skip breakfast, which increases their likelihood of overeating and eventual weight gain. Statistics show that the number of adolescents struggling with obesity, which elevates the risk for chronic health problems, has quadrupled in the past three decades. Now, MU researchers have found that eating breakfast, particularly meals rich in protein, increases young adults' levels of a brain chemical associated with feelings of reward, which may reduce food cravings and overeating ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — To address the HIV epidemic in Mexico is to address it among men who have sex with men (MSM), because they account for a large percentage of the country's new infections, says Omar Galárraga, assistant professor of health services policy and practice in the Brown University School of Public Health.

A major source of the new infections is Mexico City's male-to-male sex trade, Galárraga has found. In his research, including detailed interviews and testing with hundreds of male sex workers on the city's streets and in ...

Coordinating product placement with advertising in the same television program can reduce audience loss over commercial breaks by 10%, according to a new study in the Articles in Advance section of Marketing Science, a journal of the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS).

Synergy or Interference: The Effect of Product Placement on Commercial Break Audience Decline is by David A. Schweidel, Associate Professor of Marketing at Goizueta Business School, Emory University, Natasha Zhang Foutz, Assistant Professor of Marketing at McIntire School ...

UPTON, NY—The proteins that drive DNA replication—the force behind cellular growth and reproduction—are some of the most complex machines on Earth. The multistep replication process involves hundreds of atomic-scale moving parts that rapidly interact and transform. Mapping that dense molecular machinery is one of the most promising and challenging frontiers in medicine and biology.

Now, scientists have pinpointed crucial steps in the beginning of the replication process, including surprising structural details about the enzyme that "unzips" and splits ...

OAK RIDGE, Tenn., Oct. 15, 2014—Researchers at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory have demonstrated an additive manufacturing method to control the structure and properties of metal components with precision unmatched by conventional manufacturing processes.

Ryan Dehoff, staff scientist and metal additive manufacturing lead at the Department of Energy's Manufacturing Demonstration Facility at ORNL, presented the research this week in an invited presentation at the Materials Science & Technology 2014 conference in Pittsburgh.

"We can now ...