(Press-News.org) CHAPEL HILL – Researchers from the UNC School of Medicine have discovered that cells called fibroblasts, which normally give rise to scar tissue after a heart attack, can be turned into endothelial cells, which generate blood vessels to supply oxygen and nutrients to the injured regions of the heart, thus greatly reducing the damage done following heart attack.

This switch is driven by p53, the well-documented tumor-suppressing protein. The UNC researchers showed that increasing the level of p53 in scar-forming cells significantly reduced scarring and improved heart function after heart attack.

The finding, which was published today in the journal Nature, shows that it is possible to limit the damage wrought by heart attacks, which strike nearly one million people in the United States each year. Heart disease accounts for one in four deaths every year.

"Scientists have thought that fibroblasts are terminally differentiated, meaning they can't adopt the fate of other kinds of cells; but our study suggests this may not be entirely true," said Eric Ubil, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at UNC and first author of the Nature study.

"It appears that injury itself can induce fibroblasts to change into endothelial cells so the heart heals better. We found a drug that could push this process forward, making even more endothelial cells that help form blood vessels. The results were truly amazing in mice, and it will be exciting to see if people respond in the same way."

After a heart attack, fibroblasts replace damaged heart muscle with scar tissue. This scarring can harden the walls of the heart and lessen its ability to pump blood throughout the body. Meanwhile, endothelial cells create new blood vessels to improve circulation to the damaged area. However, sometimes these endothelial cells naturally turn into fibroblasts instead, adding to the scarring.

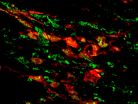

Ubil and his colleagues wondered if the switch ever flipped the other way – could fibroblasts turn into endothelial cells. To explore this idea, they induced heart attacks in mice and then studied the fibroblasts to see if the cells expressed markers characteristic of endothelial cells. To their surprise, almost a third of the fibroblasts in the area of the cardiac injury expressed these endothelial markers. The researchers found that the endothelial cells generated from fibroblasts actually gave rise to functioning blood vessels.

Next, Ubil and colleagues wanted to identify the molecule that triggered the switch. Because a heart attack is such a stressful event, Ubil created a list of genes that were known to be involved in cellular responses to stress. Topping the list was p53, a protein often called the "guardian of the genome" because it causes damaged, out of control cells to commit suicide, or apoptosis, which reduces the likelihood that they will go on to form tumors.

"As luck would have it, that was the first gene I tried, and that was the last gene I tried," said Ubil, who conducted the research as a graduate student in the laboratory of former UNC faculty member and senior study author Arjun Deb, MD.

Ubil found that p53 was "turned on" or overexpressed in the fibroblasts after heart injury and this seemed to regulate fibroblasts becoming endothelial cells. He and colleagues figured that if the p53 protein was responsible for the positive switch, then blocking it in mice would halt the transition from scar-forming cells to blood vessel-forming cells. Their experiments revealed that knocking out the p53 gene in scar-forming cells in adult mice decreased the number of cells making the switch by 50 percent.

Likewise, the researchers rationalized that upping the level of p53 would increase the number of fibroblasts that would turn into endothelial cells. Because p53 is often mutated or lost in cancer cells, a number of compounds have been designed to increase its levels as a possible anti-cancer treatment. The researchers picked one such experimental drug called RITA – Reactivation of p53 and Induction of Tumor cell Apoptosis – and used it to treat mice for a few days after cardiac injury. The drug had dramatic results, doubling the number of fibroblasts that turned into endothelial cells. That is, instead of just 30 percent of fibroblasts naturally switching into endothelial cells, 60 percent made the switch.

"The treated mice benefited tremendously," Ubil said. "There was such a huge decrease in scar formation. We checked the mice periodically, from three days to fourteen days after treatment. They had more blood vessels at the site of injury, and their heart function was better. By increasing the number of blood vessels in the injury region, we were able to greatly reduce the effects of the heart attack."

Ubil said his study shows that this could be a novel strategy for treating heart attacks. However, he cautioned that any treatments based on the discovery outlined in Nature are many years away.

"But our work shows it's possible to change the fate of scar-forming cells in the heart, and this could potentially benefit people who have heart attacks," Ubil said.

Deb added, "We are also currently investigating whether such an approach could be applied for treating scarring in other organs after injury."

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the American Heart Association and the National Institutes of Health.

Eric Ubil, PhD, is now a postdoctoral fellow at the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer center. Other UNC co-authors include graduate student Francesca Bargiacchi and Mauricio Rojas, MD, MPH. Arjun Deb, MD, is now on the faculty at UCLA.

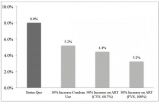

Removing a child's tonsils is one of the most common surgeries performed in the United States, with approximately 500,000 children undergoing the procedure each year. New research finds that children from lower-income families are more likely to have complications following the surgery.

In the first study of its kind to analyze post-operative complications requiring a doctor's visit within the first 14 days after tonsillectomy, researchers saw a significant disparity based on income status, race and ethnicity.

"Surprisingly, despite all children having a relatively ...

WORCESTER, MA – An international group of scientists led by Gang Han, PhD, at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, has combined a new type of nanoparticle with an FDA-approved photodynamic therapy to effectively kill deep-set cancer cells in vivo with minimal damage to surrounding tissue and fewer side effects than chemotherapy. This promising new treatment strategy could expand the current use of photodynamic therapies to access deep-set cancer tumors.

"We are very excited at the potential for clinical practice using our enhanced red-emission nanoparticles ...

Montréal, October 15, 2014 – An important scientific breakthrough by a team of IRCM researchers led by Michel Cayouette, PhD, is being published today by The Journal of Neuroscience. The Montréal scientists discovered that a protein found in the retina plays an essential role in the function and survival of light-sensing cells that are required for vision. These findings could have a significant impact on our understanding of retinal degenerative diseases that cause blindness.

The researchers studied a process called compartmentalization, which establishes ...

Do you believe in science? Your faith in science may actually make you more likely to trust information that appears scientific but really doesn't tell you much. According to a new Cornell Food and Brand Lab study, published in Public Understanding of Science, trivial elements such as graphs or formulas can lead consumers to believe products are more effective. "Anything that looks scientific can make information you read a lot more convincing," says the study's lead author Aner Tal, PhD, "The scientific halo of graphs, formulas, and other trivial elements that look scientific ...

During the 1930s, North America endured the Dust Bowl, a prolonged era of dryness that withered crops and dramatically altered where the population settled. Land-based precipitation records from the years leading up to the Dust Bowl are consistent with the telltale drying-out period associated with a persistent dry weather pattern, but they can't explain why the drought was so pronounced and long-lasting.

The mystery lies in the fact that land-based precipitation tells only part of the climate story. Building accurate computer reconstructions of historical global precipitation ...

Our mood can affect how we walk — slump-shouldered if we're sad, bouncing along if we're happy. Now researchers have shown it works the other way too — making people imitate a happy or sad way of walking actually affects their mood.

Subjects who were prompted to walk in a more depressed style, with less arm movement and their shoulders rolled forward, experienced worse moods than those who were induced to walk in a happier style, according to the study published in the Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry.

CIFAR Senior Fellow Nikolaus ...

Rochester, Minn. – The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM) offer a new guideline on how to determine what genetic tests may best diagnose a person's subtype of limb-girdle or distal muscular dystrophy. The guideline is published in the October 14, 2014, print issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the AAN.

Researchers reviewed all of the available studies on the muscular dystrophy, a group of genetic diseases in which muscle fibers are unusually susceptible to damage, as ...

COLUMBIA, Mo. – According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), many teens skip breakfast, which increases their likelihood of overeating and eventual weight gain. Statistics show that the number of adolescents struggling with obesity, which elevates the risk for chronic health problems, has quadrupled in the past three decades. Now, MU researchers have found that eating breakfast, particularly meals rich in protein, increases young adults' levels of a brain chemical associated with feelings of reward, which may reduce food cravings and overeating ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — To address the HIV epidemic in Mexico is to address it among men who have sex with men (MSM), because they account for a large percentage of the country's new infections, says Omar Galárraga, assistant professor of health services policy and practice in the Brown University School of Public Health.

A major source of the new infections is Mexico City's male-to-male sex trade, Galárraga has found. In his research, including detailed interviews and testing with hundreds of male sex workers on the city's streets and in ...

Coordinating product placement with advertising in the same television program can reduce audience loss over commercial breaks by 10%, according to a new study in the Articles in Advance section of Marketing Science, a journal of the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS).

Synergy or Interference: The Effect of Product Placement on Commercial Break Audience Decline is by David A. Schweidel, Associate Professor of Marketing at Goizueta Business School, Emory University, Natasha Zhang Foutz, Assistant Professor of Marketing at McIntire School ...