Now, a research team led by scientists at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT has unearthed one of the key players behind such drug resistance. Published in the November 25 issue of the journal Nature, the researchers pinpoint a novel cancer gene, called COT (also known as MAP3K8), and uncover the signals it uses to drive melanoma. The research underscores the gene as a new potential drug target, and also lays the foundation for a generalized approach to identify the molecular underpinnings of drug resistance in many forms of cancer.

"In melanoma as well as several other cancers, there is a critical need to understand resistance mechanisms, which will enable us to be smarter up front in designing drugs that can yield more lasting clinical responses," said senior author Levi Garraway, a medical oncologist and assistant professor at Dana-Farber and Harvard Medical School, and a senior associate member of the Broad Institute. "Our work provides an unbiased method for approaching this problem not only for melanoma, but for any tumor type."

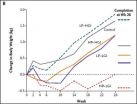

More than half of all melanoma tumors carry changes (called "mutations") in a critical gene called B-RAF. These changes not only alter the cells' genetic makeup, but also render them dependent on certain growth signals. Recent tests of drugs that selectively exploit this dependency, known as RAF inhibitors, revealed that tumors are indeed susceptible to these inhibitors — at least initially. However, most tumors quickly evolve ways to resist the drug's effects.

To explore the basis of this drug resistance, Garraway and his colleagues applied a systematic approach involving hundreds of different proteins called kinases. They chose this class of proteins because of its critical roles in both normal and cancerous cell growth. Garraway's team screened most of the known kinases in humans — roughly 600 in total — to pinpoint ones that enable drug-sensitive cells to become drug-resistant.

The approach was made possible by a resource created by scientists at the Broad Institute and the Center for Cancer Systems Biology at Dana-Farber, including Jesse Boehm, William Hahn, David Hill and Marc Vidal. The resource enables hundreds of proteins to be individually synthesized (or "expressed") in cells and studied in parallel.

From this work, the researchers identified several intriguing proteins, but one in particular stood out: a protein called COT (also known as MAP3K8). Remarkably, the function of this protein had not been previously implicated in human cancers. Despite the novelty of the result, it was not entirely surprising, since COT is known to trigger the same types of signals within cells as B-RAF. (These signals act together in a cascade known as the MAP kinase pathway.)

While their initial findings were noteworthy, Garraway and his co-workers sought additional proof of the role of COT in melanoma drug resistance. They analyzed human cancer cells, searching for ones that exhibit B-RAF mutations as well as elevated COT levels. The scientists successfully identified such "double positive" cells and further showed that the cells are indeed resistant to the effects of the RAF inhibitor.

"These were enticing results, but the gold standard for showing that something is truly relevant is to examine samples from melanoma patients," said Garraway.

Such samples can be hard to come by. They must be collected fresh from patients both before and after drug treatment. Moreover, these pre- and post- treatment samples should be isolated not just from the same patient but also from the same tumor.

Garraway and his colleagues were fortunate to obtain three such samples for analysis, thanks to their clinical collaborators led by Keith Flaherty and Jennifer Wargo at the Massachusetts General Hospital. In two out of three cases, COT gene levels became elevated following RAF inhibitor treatment or the development of drug resistance. In other cases, high levels of COT protein were evident in tissue from patients whose tumors returned or relapsed, following drug treatment. "Although we need to extend these results to larger numbers of samples, this is tantalizing clinical evidence that COT plays a role in at least some relapsing melanomas," added Garraway.

One of the critical applications of this work is to identify drugs that can be used to overcome RAF inhibitor resistance. The findings of the Nature paper suggest that a combination of therapies directed against the MAP kinase pathway – the pathway in which both B-RAF and COT are known to act – could prove effective.

"We have no doubt that other resistance mechanisms are also going to be important in B-RAF mutant melanoma," said Garraway, "but by taking a systematic approach, we should be able to find them."

###

Paper cited:

Johannessen CM et al., COT/MAP3K8 drives resistance to RAF inhibition through MAP kinase pathway reactivation. Nature DOI: 10.1038/nature09627

About Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (www.dana-farber.org) is a principal teaching affiliate of the Harvard Medical School and is among the leading cancer research and care centers in the United States. It is a founding member of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (DF/HCC), designated a comprehensive cancer center by the National Cancer Institute. It provides adult cancer care with Brigham and Women's Hospital as Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women's Cancer Center and it provides pediatric care with Children's Hospital Boston as Dana-Farber/Children's Hospital Cancer Center. Dana-Farber is the top ranked cancer center in New England, according to U.S. News & World Report, and one of the largest recipients among independent hospitals of National Cancer Institute and National Institutes of Health grant funding.

About the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard

The Eli and Edythe L. Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard was founded in 2003 to empower this generation of creative scientists to transform medicine with new genome-based knowledge. The Broad Institute seeks to describe all the molecular components of life and their connections; discover the molecular basis of major human diseases; develop effective new approaches to diagnostics and therapeutics; and disseminate discoveries, tools, methods and data openly to the entire scientific community.

Founded by MIT, Harvard and its affiliated hospitals, and the visionary Los Angeles philanthropists Eli and Edythe L. Broad, the Broad Institute includes faculty, professional staff and students from throughout the MIT and Harvard biomedical research communities and beyond, with collaborations spanning over a hundred private and public institutions in more than 40 countries worldwide. For further information about the Broad Institute, go to www.broadinstitute.org.

For more information, contact:

Nicole Davis, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard

ndavis@broadinstitute.org

617-714-7152

Robbin Ray, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

robbin_ray@dfci.harvard.edu

617-632-4090