(Press-News.org) Researchers appear to have an explanation for a longstanding question in HIV biology: how it is that the virus kills so many CD4 T cells, despite the fact that most of them appear to be "bystander" cells that are themselves not productively infected. That loss of CD4 T cells marks the progression from HIV infection to full-blown AIDS, explain the researchers who report their findings in studies of human tonsils and spleens in the November 24th issue of Cell, a Cell Press publication.

"In [infected] primary human tonsils and spleens, there is a profound depletion of CD4 T cells," said Warner Greene of The Gladstone institute for Virology and Immunology in San Francisco. "In tonsils, only one to five percent of those cells are directly infected, yet 99 percent of them die."

Lymphoid tissues, including tonsils and spleen, contain the vast majority of the body's CD4 T cells and represent the major site where HIV reproduces itself. And it now appears that those dying T cells aren't bystanders exactly.

The HIV virus apparently does invade those T cells, but the cells somehow block virus replication. It is the byproducts of that aborted infection that trigger an immune response that is ultimately responsible for killing those cells.

More specifically, when the virus enters the CD4 T cells that will later die, it begins to copy its RNA into DNA, Greene and his colleague Gilad Doitsh explain. That process, called reverse transcription, is what normally allows a virus to hijack the machinery of its host cell and begin replicating itself. But in the majority of those cells, the new findings show that the process doesn't come to completion.

The cells sense partial DNA transcripts as they accumulate and, in a misguided attempt to protect the body, commit a form of suicide. Greene says that completed viral transcripts in cells that are productively infected probably don't provoke the same reaction because they are so rapidly shuttled into the nucleus and integrated into the host's own DNA.

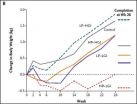

The researchers narrowed down the precise "death window" of those so-called bystander cells by taking advantage of an array of HIV drugs that act at different points in the viral life cycle. Drugs that blocked viral entry or that prevented reverse transcription altogether stopped the CD4 T cell killing, they report. Those drugs that act later in the life cycle to prevent reverse transcription only after it has already begun did not save the cells from their death.

Those cells don't die quietly either, Greene says. The cells produce ingredients that are the hallmarks of inflammation and break open, spilling all of their contents. That may provide a missing link between HIV and the inflammation that tends to go with it.

"That inflammation will attract more cells leading to more infection," Greene said. "It's a vicious cycle."

The findings also show that the CD4 T cells' demise is a response designed to be protective of the host. All that goes awry in the case of HIV and "the CD4 T cells just get blown away," compromising the immune system.

Greene said that all the available varieties of anti-HIV drugs will still work to fight the infection by preventing the virus from spreading and reducing the viral load.

The findings may lead to some new treatment strategies, however. For instance, it may be possible to develop drugs that would act on the cell sensor that triggers the immune response, helping to prevent the loss of CD 4 T cells. His team plans to explore the identity of that sensor in further studies. They also are interested to find out if the virus has strategies in place to try and prevent the CD4 T cells' death.

"The cell death pathway is really not in the virus's best interest," Greene says. "It precludes the virus from replicating and the virus may have ways to repel it."

INFORMATION: END

Researchers at the Faculty of Life Sciences (LIFE), University of Copenhagen, can now unveil the results of the world's largest diet study:

If you want to lose weight, you should maintain a diet that is high in proteins with more lean meat, low-fat dairy products and beans and fewer finely refined starch calories such as white bread and white rice. With this diet, you can also eat until you are full without counting calories and without gaining weight. Finally, the extensive study concludes that the official dietary recommendations are not sufficient for preventing obesity. ...

They are the largest fish species in the ocean, but the majestic gliding motion of the whale shark is, scientists argue, an astonishing feat of mathematics and energy conservation. In new research published today in the British Ecological Society's journal Functional Ecology marine scientists reveal how these massive sharks use geometry to enhance their natural negative buoyancy and stay afloat.

For most animals movement is crucial for survival, both for finding food and for evading predators. However, movement costs substantial amounts of energy and while this is true ...

An international team led by researchers from the Universities of Leicester and Cambridge has announced a breakthrough in identifying people at risk of developing potentially fatal blood clots that can lead to heart attack.

The discovery, published this week (25 November) in the leading haematology journal Blood, is expected to advance ways of detecting and treating coronary heart disease – the most common form of disease affecting the heart and an important cause of premature death.

The research led by Professor Alison Goodall from the University of Leicester and Professor ...

A new treatment has been developed for sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSHL), a condition that causes deafness in 40,000 Americans each year, usually in early middle-age. Researchers writing in the open access journal BMC Medicine describe the positive results of a preliminary trial of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), applied as a topical gel.

Takayuki Nakagawa, from Kyoto University, Japan, worked with a team of researchers to test the gel in 25 patients whose SSHL had not responded to the normal treatment of systemic gluticosteroids. He said, "The results indicated ...

Every 5°C rise in maximum temperature pushes up the rate of hospital admissions for serious injuries among children, reveals one of the largest studies of its kind published online in Emergency Medicine Journal.

Conversely, each 5° C drop in the minimum daily temperature boosts adult admissions for serious injury by more than 3%, while snow prompts an 8% rise, the research shows.

The authors base their findings on the patterns of hospital treatment for both adults and children in 21 emergency care units across England, belonging to the Trauma Audit and research Network ...

Workplace asthma costs the UK at least £100 million a year, and may be as high as £135 million, reveals research published online in Thorax.

An estimated 3,000 new cases of occupational asthma are diagnosed every year in the UK, but the condition is under diagnosed, say the authors.

They reviewed published data on the costs of all asthma and workplace asthma, as well as the impact costs.

The evidence was then used to calculate the costs of workplace asthma on an individual's ability to work and their wider life, including their use of health services, based on a ...

New research from the Emory University School of Medicine offers reassurance for nursing mothers with epilepsy. According to a study published in the November 24 online issue of Neurology, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology, breastfeeding a baby while taking a seizure medication may have no harmful effect on the child's IQ later in life.

"Our results showed no difference in IQ scores between the children who were breastfed and those who were not," says study author Kimford Meador, MD, professor of neurology, Emory University School of Medicine and ...

Chronic jet lag alters the brain in ways that cause memory and learning problems long after one's return to a regular 24-hour schedule, according to research by University of California, Berkeley, psychologists.

Twice a week for four weeks, the researchers subjected female Syrian hamsters to six-hour time shifts – the equivalent of a New York-to-Paris airplane flight. During the last two weeks of jet lag and a month after recovery from it, the hamsters' performance on learning and memory tasks was measured.

As expected, during the jet lag period, the hamsters had trouble ...

Toronto, ON – November 24 – It's never fun riding the bench – but could it also make you less likely to be physically active in the future?

That's one of the questions being explored by Mark Eys, an associate professor of kinesiology and physical education at Wilfrid Laurier University and the Canada Research Chair in Group Dynamics and Physical Activity. Eys is presenting his work as part of this week's Canada Research Chairs conference in Toronto.

Eys, who also teaches out of the university's psychology department, is studying group cohesion – which, in sporting ...

Bonn, 24th November 2010. Metformin, a drug used in type 2-diabetes might have the potential to also act against Alzheimer's disease. This has been shown in a study from scientists of the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), the University of Dundee and the Max-Planck-Institute for Molecular Genetics. The researchers have found out that the diabetes drug metformin counteracts alterations of the cell structure protein Tau in mice nerve cells. These alterations are a main cause of the Alzheimer's disease. Moreover, they uncovered the molecular mechanism of ...