Males with IBS report more social stress than females, UB study finds

Importance of gender-based studies is highlighted by unexpected findings, UB health psychologist says

2014-10-20

(Press-News.org) BUFFALO, N.Y. — One of the few studies to examine gender differences among patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has found that males with the condition experience more interpersonal difficulties than do females with the condition. The findings challenge what had been predicted by the University at Buffalo investigator and his colleagues.

The study, "Understanding gender differences in IBS: the role of stress from the social environment," is being presented during the Oct. 19 poster session at the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) annual meeting in Philadelphia.

The research, featured on ACG's blog at http://acgblog.org/2014/10/14/understanding-gender-differences-in-ibs-the-role-of-stress-from-the-social-environment/, was selected as a Presidential Poster session, which recognizes highly novel and significant research; the designation is given to less than 5 percent of the more than 2,000 abstracts being exhibited.

"Our findings underscore the significance of studying gender-based differences in how people experience the same disease or condition," says Jeffrey Lackner, PsyD, professor of medicine in the UB School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

IBS is among the most common, disabling and intractable gastrointestinal disorders. Symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea and/or constipation. It is estimated to affect between 25 million and 50 million Americans. Because IBS is twice as common among women as men, far less is known about how men experience the disease.

The UB study revealed little difference between genders in the severity of their gastrointestinal symptoms.

Previous psychological research findings had suggested that males with IBS take on stereotypically feminine traits, including passive and accommodating behaviors, according to Lackner and his co-authors.

But the UB study has found that males report feeling cold and detached, and as though they have a need to dominate their relationships with others. Males, not females, report having more difficulties in interpersonal relationships.

"That discrepancy underscores our need to move beyond clinical intuition and anecdote, and systematically study the different ways that each gender experiences disease in general," says Lackner.

The findings may have relevance to the ways that male IBS patients interact with their doctors, he says. "Patients who have a domineering and distant interpersonal style may need to work more closely with the physicians," says Lackner.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors are from Wayne State, Northwestern and University of Wisconsin-Parkside. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-10-20

Being depressed is depressing in itself and makes you feel even worse. That is one reason why it is so hard to break out of depressive conditions.

New research out of Queen's University offers a new approach to do just that. Nikolaus Troje (Psychology, Biology and School of Computing) along with clinical psychologists from the University of Hildesheim, Germany, have shown that walking in a happy or sad style actually affects our mood. Subjects who were prompted to walk in a more depressed style, with less arm movement and their shoulders rolled forward, experienced worse ...

2014-10-20

A drug being studied as a fast-acting mood-lifter restored pleasure-seeking behavior independent of – and ahead of – its other antidepressant effects, in a National Institutes of Health trial. Within 40 minutes after a single infusion of ketamine, treatment-resistant depressed bipolar disorder patients experienced a reversal of a key symptom – loss of interest in pleasurable activities – which lasted up to 14 days. Brain scans traced the agent's action to boosted activity in areas at the front and deep in the right hemisphere of the brain.

"Our ...

2014-10-20

Ever wondered how people figure out what is fair? Look to the brain for the answer. According to a new Norwegian brain study, people appreciate fairness in much the same way as they appreciate money for themselves, and also that fairness is not necessarily that everybody gets the same income.

Economists from the Norwegian School of Economics (NHH) and brain researchers from the University of Bergen (UiB) have worked together to assess the relationship between fairness, equality, work and money. Indeed, how do our brains react to how income is distributed?

More precisely, ...

2014-10-20

Microscopic particles that bind under low temperatures will melt as temperatures rise to moderate levels, but re-connect under hotter conditions, a team of New York University scientists has found. Their discovery points to new ways to create "smart materials," cutting-edge materials that adapt to their environment by taking new forms, and to sharpen the detail of 3D printing.

"These findings show the potential to engineer the properties of materials using not only temperature, but also by employing a range of methods to manipulate the smallest of particles," explains ...

2014-10-20

The health and environmental implications of fossil fuel exploitation, nuclear waste or mining-related pollution are some of the more well-known effects of the increasing energy and material use of the global economy. One way to confront environmental injustice is to use economic evaluation tools. Environmental Justice Organisations (EJOs) are conducting cost-benefit analyses (CBAs) and multi-criteria analyses (MCA) with the support of academics, in order to explore and reveal the un-sustainability of environmentally controversial projects. In some cases, that strategy ...

2014-10-20

An international research collaboration led by UC San Francisco researchers has identified a genetic variant common in Latina women that protects against breast cancer.

The variant, a difference in just one of the three billion "letters" in the human genome known as a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), originates from indigenous Americans and confers significant protection from breast cancer, particularly the more aggressive estrogen receptor–negative forms of the disease, which generally have a worse prognosis.

"The effect is quite significant," said Elad ...

2014-10-20

Blind cave fish may not be the first thing that comes to mind when it comes to understanding human sight, but recent research indicates they may have quite a bit to teach us about the causes of many human ailments, including those that result in loss of sight. A team of researchers, led by Suzanne McGaugh, an assistant professor in the University of Minnesota's College of Biological Sciences, is looking to the tiny eyeless fish for clues about the underpinnings of degenerative eye disease and more. A new study, published in the October 20 online edition of Nature Communications, ...

2014-10-20

Head Start programs may help low-income parents improve their educational status, according to a new study by Northwestern University researchers.

The study is one of the first to examine whether a child's participation in the federal program benefits mothers and fathers – in particular parents' educational attainment and employment.

"Studies on early childhood education programs have historically focused on child outcomes," said study lead author Terri Sabol, an Assistant Professor of Human Development and Social policy at Northwestern's School of Education ...

2014-10-20

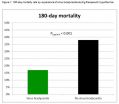

Geneva, Switzerland – 20 October 2014: Researchers may have developed a way to potentially assist prognostication in the first 24 hours after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) when patients are still in a coma. Their findings are revealed today at Acute Cardiovascular Care 2014 by Dr Jakob Hartvig Thomsen from Copenhagen, Denmark.

Acute Cardiovascular Care is the annual meeting of the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association (ACCA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and takes place 18-20 October in Geneva, Switzerland.

Dr Thomsen said: "When we talk ...

2014-10-20

According to Nationwide Children's Hospital researchers, 63,000 children under the age of six experienced out-of-hospital medication errors annually between 2002 and 2012. One child is affected every eight minutes, usually by a well-meaning parent or caregiver unintentionally committing a medication error.

The most common medication mistakes in children under the age of six occur in the children's home, or another residence and school. The most common medicines involved are painkillers and fever-reducers like ibuprofen and acetaminophen.

"This is more common than people ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Males with IBS report more social stress than females, UB study finds

Importance of gender-based studies is highlighted by unexpected findings, UB health psychologist says