(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA – (Oct. 21, 2014) – A team of scientists, led by researchers at The Wistar Institute, has identified a possible explanation for why middle-aged adults were hit especially hard by the H1N1 influenza virus during the 2013-2014 influenza season. The findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, offer evidence that a new mutation in H1N1 viruses potentially led to more disease in these individuals. Their study suggests that the surveillance community may need to change how they choose viral strains that go into seasonal influenza vaccines, the researchers say.

"We identified a mutation in recent H1N1 strains that allows viruses to avoid immune responses that are present in a large number of middle-aged adults," said Scott Hensley, Ph.D., a member of Wistar's Vaccine Center and an assistant professor in the Translational Tumor Immunology program of Wistar's Cancer Center.

Historically, children and the elderly are most susceptible to the severe effects of the influenza viruses, largely because they have weaker immune systems. However, during the 2013-2014 physicians saw an unusually high level of disease due to H1N1 viruses in middle-aged adults—those who should have been able to resist the viral assault. Although H1N1 viruses recently acquired several mutations in the hemagglutinin (HA) glycoprotein, standard serological tests used by surveillance laboratories indicate that these mutations do not change the viruses' antigenic properties.

However, Wistar researchers have shown that, in fact, one of these mutations is located in a region of HA that allows viruses to avoid antibody responses elicited in some middle-aged adults. Specifically, they found that 42 percent of individuals born between 1965 and 1979 possess antibodies that recognize the region of HA that is now mutated. The Wistar researchers suggest that new viral strains that are antigenically matched in this region should be included in future influenza vaccines.

"Our immune systems are imprinted the first time that we are exposed to influenza virus," Hensley said. "Our data suggest that previous influenza exposures that took place in the 1970s and 1980s influence how middle-aged people respond to the current H1N1 vaccine."

The researchers noted that significant antigenic changes of influenza viruses are mainly determined using anti-sera isolated from ferrets recovering from primary influenza infections. However humans are typically re-infected with antigenically distinct influenza strains throughout their life. Therefore, antibodies that are used for surveillance purposes might not be fully reflective of human immunity.

"The surveillance community has a really challenging task and they do a great job, but we may need to re-evaluate how we, as a community, detect antigenically distinct influenza strains and how we choose vaccine strains," says Hensley. "It makes sense to base these analyses on human antibodies."

Vaccines work by stimulating the immune system to produce antibody proteins against particles (called antigens) from an infectious agent, such as bacteria or a virus. The immune system saves the cells that produce effective antibodies, which then provide immunity against future attacks by the same or similar infectious agents. Despite the availability of a vaccine, seasonal influenza typically kills 36,000 Americans, alone, and nearly a half million individuals around the world, in total, each year.

"Without a doubt, the best way to prevent getting influenza infection is to receive an influenza vaccine," explained Hensley. "Right now influenza vaccines are pretty effective, but our studies suggest ways that we can potentially make them work even better."

INFORMATION:

The portion of this research conducted at The Wistar Institute was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases under awards R01AI113047 and 1R01AI108686. The study also utilized Wistar's shared facilities, which are funded by the Institute's National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA010815).

Members of the Hensley laboratory that co-authored this study include Susanne L. Linderman, Benjamin S. Chambers, Seth J. Zost, Kaela Parkhouse, Yang Li and Christin Herrmann. Additional co-authors include: Ali H. Ellebedy and Rafi Ahmed of Emory University; Donald M. Carter and Ted M. Ross of the Vaccine and Gene Therapy Institute of Florida; Sarah F. Andrews, Nai-Ying Zheng, Min Huang, Yunping Huang, and Patrick C. Wilson of The University of Chicago; Donna Strauss and Beth H. Shaz of the New York Blood Center; Richard L. Hodinka of the University of Pennsylvania; Gustavo Reyes-Teran of the National Institute of Respiratory Diseases of Mexico; and Jesse D. Bloom of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

The Wistar Institute is an international leader in biomedical research with special expertise in cancer research and vaccine development. Founded in 1892 as the first independent nonprofit biomedical research institute in the country, Wistar has long held the prestigious Cancer Center designation from the National Cancer Institute. The Institute works actively to ensure that research advances move from the laboratory to the clinic as quickly as possible. The Wistar Institute: Today's Discoveries – Tomorrow's Cures. On the Web at http://www.wistar.org

HUNTSVILLE, TX (10/21/14) -- One out of every five female students experience stalking victimization during their college career, but many of those cases are not reported to police, according to a study by the Crime Victims' Institute (CVI) at Sam Houston State University.

The rate of stalking on college campuses is higher than those experienced by the general public, according to research. Many of the victims fail to report the incidents because they feel the situation was too minor, feared revenge, saw it as a private or personal matter, or thought police would not ...

Russian scientists have developed a theoretical model of quantum memory for light, adapting the concept of a hologram to a quantum system. These findings from Anton Vetlugin and Ivan Sokolov from St. Petersburg State University in Russia are published in a study in EPJD. The authors demonstrate for the first time that it is theoretically possible to retrieve, on demand, a given portion of the stored quantised light signal of a holographic image – set in a given direction in a given position in time sequence. This is done by shaping the control field both in space ...

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) — Researchers have created a cellular probe that combines a tarantula toxin with a fluorescent compound to help scientists observe electrical activity in neurons and other cells. The probe binds to a voltage-activated potassium ion channel subtype, lighting up when the channel is turned off and dimming when it is activated.

This is the first time researchers have been able to visually observe these electrical signaling proteins turn on without genetic modification. These visualization tools are prototypes of probes that could some day help ...

Some people suffer incipient dementia as they get older. To make up for this loss, the brain's cognitive reserve is put to the test. Researchers from the University of Santiago de Compostela have studied what factors can help to improve this ability and they conclude that having a higher level of vocabulary is one such factor.

'Cognitive reserve' is the name given to the brain's capacity to compensate for the loss of its functions. This reserve cannot be measured directly; rather, it is calculated through indicators believed to increase this capacity.

A research project ...

Scientists from Queen's University Belfast have been involved in a groundbreaking discovery in the area of experimental physics that has implications for understanding how radiotherapy kills cancer cells, among other things.

Dr Jason Greenwood from Queen's Centre for Plasma Physics collaborated with academics from Italy and Spain on the work on electrons, which has been published in the international journal Science.

Using some of the shortest laser pulses in the world, the researchers used strobe lighting to track the ultra-fast movement of the electrons within a nanometer-sized ...

A new study led by researchers at King's College London in collaboration with the University of Manchester and the University of Dundee has found a strong link between exposure to peanut protein in household dust during infancy and the development of peanut allergy in children genetically predisposed to a skin barrier defect.

Around 2% of school children in the UK and the US are allergic to peanuts. Severe eczema in early infancy has been linked to food allergies, particularly peanut allergy. A major break-through in the understanding of eczema developed with the discovery ...

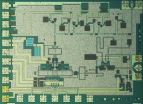

Fewer cords, smaller antennas and quicker video transmission. This may be the result of a new type of microwave circuit that was designed at Chalmers University of Technology. The research team behind the circuits currently holds an attention-grabbing record. Tomorrow the results will be presented at a conference in San Diego.

Every time we watch a film clip on our phone or tablet, an entire chain of advanced technology is involved. In order for the film to start playing in an even sequence when we press the play button, the data must reach us quickly via a long series ...

An experimental drug currently being trialled for influenza and Ebola viruses could have a new target: norovirus, often known as the winter vomiting virus. A team of researchers at the University of Cambridge has shown that the drug, favipiravir, is effective at reducing – and in some cases eliminating – norovirus infection in mice.

Norovirus is the most common cause of gastroenteritis in the UK. For most people, infection causes an unpleasant but relatively short-lived case of vomiting and diarrhoea, but chronic infection can cause major health problems for ...

Amsterdam, October 21, 2014 – Flu vaccines are known to have a protective effect against heart disease, reducing the risk of a heart attack. For the first time, this research, published in Vaccine, reveals the molecular mechanism that underpins this phenomenon. The scientists behind the study say it could be harnessed to prevent heart disease directly.

Heart disease is the leading cause of death worldwide. People can reduce their risk of heart disease by eating healthily, exercising and stopping smoking. However, to date there is no vaccine against heart disease.

Previous ...

Cosmologists have made the most sensitive and precise measurements yet of the polarization of the cosmic microwave background.

The report, published October 20 in the Astrophysical Journal, marks an early success for POLARBEAR, a collaboration of more than 70 scientists using a telescope high in Chile's Atacama desert designed to capture the universe's oldest light.

"It's a really important milestone," said Kam Arnold, the corresponding author of the report who has been working on the instrument for a decade. "We're in a new regime of more powerful, precision cosmology." ...