(Press-News.org) La Jolla, Calif., October 23, 2014 –A new study by researchers at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute reveals the process that leads to changes in the brains of individuals with Down syndrome—the same changes that cause dementia in Alzheimer's patients. The findings, published in Cell Reports, have important implications for the development of treatments that can prevent damage in neuronal connectivity and brain function in Down syndrome and other neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative conditions, including Alzheimer's disease.

Down syndrome is characterized by an extra copy of chromosome 21 and is the most common chromosome abnormality in humans. It occurs in about one per 700 babies in the United States, and is associated with a mild to moderate intellectual disability. Down syndrome is also associated with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. By the age of 40, nearly 100 percent of all individuals with Down syndrome develop the changes in the brain associated with Alzheimer's disease, and approximately 25 percent of people with Down syndrome show signs of Alzheimer's-type dementia by the age of 35, and 75 percent by age 65. As the life expectancy for people with Down syndrome has increased dramatically in recent years—from 25 in 1983 to 60 today—research aimed to understand the cause of conditions that affect their quality of life are essential.

"Our goal is to understand how the extra copy of chromosome 21 and its genes cause individuals with Down syndrome to have a greatly increased risk of developing dementia," said Huaxi Hu, Ph.D., professor in the Degenerative Diseases Program at Sanford-Burnham and senior author of the paper. "Our new study reveals how a protein called sorting nexin 27 (SNX27) regulates the generation of beta-amyloid—the main component of the detrimental amyloid plaques found in the brains of people with Down syndrome and Alzheimer's. The findings are important because they explain how beta-amyloid levels are managed in these individuals."

Beta-Amyloid, Plaques and Dementia

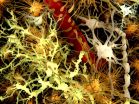

Xu's team found that SNX27 regulates beta-amyloid generation. Beta-amyloid is a sticky protein that's toxic to neurons. The combination of beta-amyloid and dead neurons form clumps in the brain called plaques. Brain plaques are a pathological hallmark of Alzheimer's disease and are implicated in the cause of the symptoms of dementia.

"We found that SNX27 reduces beta-amyloid generation through interactions with gamma-secretase—an enzyme that cleaves the beta-amyloid precursor protein to produce beta-amyloid," said Xin Wang, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Xu's lab and first author of the publication. "When SNX27 interacts with gamma-secretase, the enzyme becomes disabled and cannot produce beta-amyloid. Lower levels of SNX27 lead to increased levels of functional gamma-secretase that in turn lead to increased levels of beta-amyloid."

SNX27's Role in Brain Function

Previously, Xu and colleagues found that SNX27 deficient mice shared some characteristics with Down syndrome, and that humans with Down syndrome have significantly lower levels of SNX27. In the brain, SNX27 maintains certain receptors on the cell surface—receptors that are necessary for neurons to fire properly. When levels of SNX27 are reduced, neuron activity is impaired, causing problems with learning and memory. Importantly, the research team found that by adding new copies of the SNX27 gene to the brains of Down syndrome mice, they could repair the memory deficit in the mice.

The researchers went on to reveal how lower levels of SNX27 in Down syndrome are the result of an extra copy of an RNA molecule encoded by chromosome 21 called miRNA-155. miRNA-155 is a small piece of genetic material that doesn't code for protein, but instead influences the production of SNX27.

With the current study, researchers can piece the entire process together—the extra copy of chromosome 21 causes elevated levels of miRNA-155 that in turn lead to reduced levels of SNX27. Reduced levels of SNX27 lead to an increase in the amount of active gamma-secretase causing an increase in the production of beta-amyloid and the plaques observed in affected individuals.

"We have defined a rather complex mechanism that explains how SNX27 levels indirectly lead to beta-amyloid," said Xu. "While there may be many factors that contribute to Alzheimer's characteristics in Down syndrome, our study supports an approach of inhibiting gamma-secretase as a means to prevent the amyloid plaques in the brain found in Down syndrome and Alzheimer's."

"Our next step is to develop and implement a screening test to identify molecules that can reduce the levels of miRNA-155 and hence restore the level of SNX27, and find molecules that can enhance the interaction between SNX27 and gamma-secretase. We are working with the Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics at Sanford-Burnham to achieve this," added Xu.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported in part by US NIH/National Cancer Institute Grant AG038710, AG021173, NS046673, AG030197 and AG044420, and grants from the Alzheimer's Association, the Global Down Syndrome Foundation, the American Health Assistance Foundation and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

About Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute

Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute is dedicated to discovering the fundamental molecular causes of disease and devising the innovative therapies of tomorrow. Sanford-Burnham takes a collaborative approach to medical research with major programs in cancer, neurodegeneration and stem cells, diabetes, and infectious, inflammatory, and childhood diseases. The Institute is recognized for its National Cancer Institute-designated Cancer Center, its NIH-designated Neuroscience Center Cores, and expertise in drug discovery technologies. Sanford-Burnham is a nonprofit, independent institute that employs more than 1,000 scientists and staff in San Diego (La Jolla), Calif., and Orlando (Lake Nona), Fla. For more information, visit us at sanfordburnham.org.

Sanford-Burnham can also be found on Facebook at facebook.com/sanfordburnham and on Twitter @sanfordburnham.

Exosomes, tiny, virus-sized particles released by cancer cells, can bioengineer micro-RNA (miRNA) molecules resulting in tumor growth. They do so with the help of proteins, such as one named Dicer. New research from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center suggests Dicer may also serve as a biomarker for breast cancer and possibly open up new avenues for diagnosis and treatment. Results from the investigation were published in today's issue of Cancer Cell.

"Exosomes derived from cells and blood serum of patients with breast cancer, have been shown to initiate ...

A comprehensive analysis of the genomes of nearly 500 papillary thyroid carcinomas (PTC) – the most common form of thyroid cancer – has provided new insights into the roles of frequently mutated cancer genes and other genomic alterations that drive disease development. The findings also may help improve diagnosis and treatment. Investigators with The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network identified new molecular subtypes that will help clinicians determine which tumors are more aggressive and which are more likely to respond to certain treatments. Their ...

SUMMERLAND, BRITISH COLUMBIA - A new study says that cherry producers need to understand new intricacies of the production-harvest-marketing continuum in order to successfully move sweet cherries from growers to end consumers. For example, the Canadian sweet cherry industry has had to modify logistics strategies--from shorter truck or air shipping to long-distance containerized shipping--to accommodate burgeoning export markets. Keeping cherries fresh and consumer-ready during long ocean crossings challenges producers to find new ways to retain fruit quality for weeks. ...

PASADENA, Calif., October 23, 2014 — The rate of non-Hispanic white youth diagnosed with type 1 diabetes increased significantly from 2002 to 2009 in all but the youngest age group of children, according to a new study published today in the journal Diabetes.

The study included data from more than 2 million children and adolescents living in diverse geographic regions of the United States. Within this population, researchers identified 5,842 non-Hispanic white youth, 19 years old and younger, newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes over the 8-year study period. They ...

Internet users regularly receive all kinds of personalized content, from Google search results to product recommendations on Amazon. This is thanks to the complex algorithms that produce results based on users' profiles and past activity. It's Big Data at work, and it's often advantageous for users. But such personalization can also be a disadvantage to buyers, according to a team of Northeastern University researchers, when e-commerce websites manipulate search results or customize prices without the user's knowledge—and which in some cases leads to some online shoppers ...

Ewing sarcoma tumors disappeared and did not return in more than 70 percent of mice treated with combination therapy that included drugs from a family of experimental agents developed to fight breast cancer, reported St. Jude Children's Research Hospital scientists. The study will appear in the November 6 edition of the scientific journal Cell Reports.

The treatment paired two chemotherapy drugs currently used to treat Ewing sarcoma (EWS) with experimental drugs called poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors that interfere with DNA repair. PARP inhibitors are currently ...

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Nearly two-thirds of patients treated for colorectal cancer reported some measure of financial burden due to their treatment, according to a new study from researchers at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

The burden was greatest among patients who received chemotherapy and among younger patients who worked in low-paying jobs.

The study surveyed 956 patients who had been treated for stage 3 colorectal cancer. Among this group, chemotherapy is known to increase survival by up to 20 percent and is routinely recommended following ...

The strong southwesterly wind shear that has been battering Tropical Storm Ana has abated and has given the storm a chance to re-organize. Ana appeared more rounded on imagery from NASA's Terra satellite as thunderstorms again circled the low-level center.

NASA's Terra satellite passed over Ana on Oct. 22 at 22:10 UTC (6:10 p.m. EDT). The MODIS instrument aboard Terra captured a visible image of the storm that showed clouds and showers were no longer being blown northeast of the center from southwesterly wind shear, as they had in the last couple of days. The wind shear ...

Avoiding power struggles in the grocery store with children begging for sweets, chips and other junk foods – and parents often giving in – could be helped by placing the healthier options at the eye level of children and moving the unhealthy ones out of the way.

A new study by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health found that this dynamic is particularly frustrating for caregivers on limited budgets who are trying to save money and make healthy meals.

The study, part of a project designed to encourage healthy food purchasing ...

A team of researchers led by a Wayne State University School of Medicine associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology has published findings that provide novel insight into the cause of preeclampsia, the leading cause of maternal and infant death worldwide, a discovery that could lead to the development of new therapeutic treatments.

Nihar Nayak, D.V.M., Ph.D., is the principal investigator of the study, "Endometrial VEGF induces placental sFLT1 and leads to pregnancy complications," published Oct. 20 in the online version of The Journal of Clinical Investigation. ...